For the past month, my wife Jody has been providing me with fantasy and gaming inspired cartoons that channel the old cartoons that used to be so prominent in gaming magazines like Dragon and The Space Gamer. This week's entry is the first that will be in color.

I'm happy to see that in the weeks since I have started these posts that Wizard's of the Coast has decided to start including cartoons on their website. I don't think I had any influence on their decision, but it is nice to see we are thinking in the same nostalgic way.

Showing posts sorted by relevance for query space gamer. Sort by date Show all posts

Showing posts sorted by relevance for query space gamer. Sort by date Show all posts

Wednesday, June 01, 2011

Friday, October 03, 2014

Classic Horror RPG CHILL Rises from the Dead with New Kickstarter

Before I get into the details of what my ideal new edition of the CHILL role playing game is, I'd like to take a moment to thank Matthew McFarland and Michelle Lyons-McFarland for taking the time to acquire the license to this classic game and put together what looks to be a very solid horror role playing game.

If you are a fan of horror role playing games and want to help small press publishers succeed, then you should back the brand new Chill 3rd Edition Kickstarter. I'm a backer and I will be blogging about the game's playtest rules very soon.

,

Now that I've cleared the air and made it clear that I am excited about the game that Matthew and Michelle are putting together, I'm going to gripe. That's what we obsessives do when things aren't perfect, we gripe. But I'm not going to gripe in an non-constructive manner. This isn't about what I think Matthew and Michelle are doing wrong, it's about what I wish they would ALSO do.

If you were to ask me what my favorite genres of film are, I would without hesitation tell you that they are romantic comedies and horror movies. You are probably wondering what When Harry Met Sally and Hostel have in common that I would rank the genres of these two films so highly. I would tell you that I don't think Hostel is a "horror" movie. Being pedantic, I'd try to convince you that it was splatterpunk or back track and change the word horror to weird. When it comes to weird and fantastic tales, my heart has two great loves Ray Harryhausen and Hammer Studios. It is the horror of the kind that Hammer Studios made, and now makes again, that I love. Give me stuffy Victorian/Edwardian era investigators encountering terrors from the unknown with a skepticism that is fueled by emerging scientific discoveries, and you have warmed my heart to know end. If you add to that a romantic element - which can either be of the courtship or familial variety - and I'm all in. Films like Horror of Dracula, Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed, and The Woman in Black are rich in mood and capture the imagination and are perfect for adaptation to role playing. The original Chill role playing game attempted to emulate this kind of storytelling, and I loved it because of it.

The rules for the original Chill role playing game were easy to learn and perfectly designed for new gamers. It was the combination of ease of play and Hammer Horror that I believe led to Rick Swan's negative review in The Complete Guide to Role-Playing Games. Other publications like Space Gamer and Different Worlds gave the game much higher praise - I'll share those reviews in a future blog post - and seemed to understand that Chill was the introductory game in a series of games that became increasingly complex as their genre required. The Goblinoid Games blog has a great description of the original Pacesetter system and they are the publisher of some of the other Pacesetter System games. Goblinoid Games has also designed their own horror game inspired by the horror movies of the 80s which I blogged about at Blackgate Magazine.

When I read the description for the new edition of Chill, it was immediately clear that the game would not be my idealized version of the game. The description referenced the Mayfair edition of the game, a game that tried to be "edgier" in order to compete with Call of Cthulhu. I've also seen Matthew's Facebook discussion of the game and he mentions how his version will treat mental illness. I'll be the first to admit that Call of Cthulhu doesn't do a good job representing actual mental illness, but neither does the fiction it is emulating. Lovecraft's fiction is about a descent into a particular kind of madness as understood at a particular time. Having said that, my idealized version of Chill would have no rules for insanity. It would only have rules for fear and shock. Hammer stories aren't about protagonists who are slowly driven insane as their world view is shattered. Instead, they are about the success and failure of the rational to engage with the supernatural.

The new Chill's artwork hints that it is inspired by many of the horror films currently on the market, with no small touch of American Horror Story. This is not a bad thing. In fact, if one ignores the shifting of time period that's pretty close to the Hammer tone...and films like Mama have demonstrated that the classic Ghost Story has legs. That's my longish way of saying that I'd like Matthew and Michelle to release a Victorian/Hammer supplement for Chill and that I hope their game system is quick easy and intuitive. My first read through the quick start rules gives me reason to believe at least half of that will happen...the rules part.

When I read the description for the new edition of Chill, it was immediately clear that the game would not be my idealized version of the game. The description referenced the Mayfair edition of the game, a game that tried to be "edgier" in order to compete with Call of Cthulhu. I've also seen Matthew's Facebook discussion of the game and he mentions how his version will treat mental illness. I'll be the first to admit that Call of Cthulhu doesn't do a good job representing actual mental illness, but neither does the fiction it is emulating. Lovecraft's fiction is about a descent into a particular kind of madness as understood at a particular time. Having said that, my idealized version of Chill would have no rules for insanity. It would only have rules for fear and shock. Hammer stories aren't about protagonists who are slowly driven insane as their world view is shattered. Instead, they are about the success and failure of the rational to engage with the supernatural.

The new Chill's artwork hints that it is inspired by many of the horror films currently on the market, with no small touch of American Horror Story. This is not a bad thing. In fact, if one ignores the shifting of time period that's pretty close to the Hammer tone...and films like Mama have demonstrated that the classic Ghost Story has legs. That's my longish way of saying that I'd like Matthew and Michelle to release a Victorian/Hammer supplement for Chill and that I hope their game system is quick easy and intuitive. My first read through the quick start rules gives me reason to believe at least half of that will happen...the rules part.

Tuesday, September 15, 2009

Responding to Things We Think About Games -- Gaming Expectations: Heroic Endings or Doomed to Failure (Case Study One: Robotron 2084)

In 2008, game designers Will Hindmarch and Jeff Tidball released a very useful book entitled Things we Think About Games. The book contains 101 statements by the authors, with a couple of additional statements by guest gamers/designers. Some of the comments are common sense, some are blunt, and all are thought provoking. Things We Think About Games is a book that belongs on every gamer's bookshelf, and Will and Jeff's website belongs on every gamers rss feed.

is a book that belongs on every gamer's bookshelf, and Will and Jeff's website belongs on every gamers rss feed.

At the San Diego Comic Con this year, I asked Jeff Tidball if he would allow me to write a series of posts featuring the statements from the book. Each blog post would be a gamer reacting to one of the statements in the book, and eventually I'd like to address all the statements made by the various game designers. I will also continually belabor the fact that Will and Jeff asked Wil Wheaton, and not me, to write the introduction to the book. While this is a common mistake, it is one that I will point out at every opportunity. Yes, Wheaton is more famous (and is in Secret of Nimh which I recommended as last week's Hulu recommendation), but I am less likely to use expletives.

This being a blog, and not a Thesis or Dissertation, I will address the statements in no particular order, but I do hope to address them all. Today's blog topic is inspired by the 101st entry in the book.

The statement is simple enough, and is a gamer's version of Oracle of Delphi's famous dictum Gnōthi sauton or "Know Thyself." It is a statement seems to have an underlying claim that some ludophile Socrates might adhere to, "the unexamined gaming experience isn't worth playing." That may, in one way, be the whole point of Hindmarch's and Tidball's book, but this quote provides a nice starting point for any discussion regarding games and spurs one on to think philosophically about the subject.

It was this thought that was lurking around my subconscious when I read an article at Gamasutra about Robotron 2084. The article is an historical article about the game and its legacy with regard to game play. A good amount of time is spent discussing the games innovative use of a two joystick system, an innovation that couldn't be accurately emulated in a "home experience" for many years. It makes for interesting reading, but there was one quote which mixed with STATEMENT 101 to inspire me to think about why I play games. The quote was a simple one, "The player is tasked with the grim, desperate, and ultimately futile task of saving the last family of Humanoids (emphasis added)."

Ultimately futile -- the words echoed in the back of my mind.

Why would I want to play a game that I cannot, no matter how skilled I get at it, "win?"

What particularly bothered me about this statement is that it pointed to a contradiction in my game playing habits. I have been a fan of Robotron 2084 for decades and have played it uncountable times. In that time my skill level has migrated, from poor to excellent to poor to average, depending on how often I have played the game during a given time period. I am not always in the mood for Robotron, but I never find the game -- as it was designed -- to be a bad game. As big a fan as I am of this particular futile effort, I was seriously disappointed by the end of Dawn Of War . After many hours of game play, and total victory over the forces of Chaos, I watched as all my hard work evaporated in a "1970s Satan has eaten your soul Bad ending" as my Space Marine Captain unwittingly released a new demon into the universe.

. After many hours of game play, and total victory over the forces of Chaos, I watched as all my hard work evaporated in a "1970s Satan has eaten your soul Bad ending" as my Space Marine Captain unwittingly released a new demon into the universe.

The futility of all my hard work playing Dawn of War was made clear to me during the final animated narrative sequence. Lucien Soulban's scripted ending undid everything I had struggled for in playing the game -- and it seriously aggravated me. I was all the more aggravated because an author/game designer I respect was the one who dropped the "futility bomb" on my head.

Why was I experiencing such a strong emotion that was, on its face, a contradictory sentiment to my thorough enjoyment of the equally futile Robotron 2084? To answer this, it was helpful to contemplate statement 101.

Why do I play games?

I play different games for a variety of reasons, but one reason that keeps me coming back is "story." I like the way that games, of all kinds, tell stories. It's one of the reasons I am a "good loser." I don't mind losing to someone who is better than me at Chess, all I want is my learning experience to be a good story. Candyland, with its pre-determined gameplay, taught me the importance of story in play and de-emphasized "winning." Both Robotron 2084 and Dawn of War contain story elements. Robotron's appear to be "weak" at first, but they are deeply embedded in gameplay -- if simple narratively. Both games contain narratives where the actions of the player, in the end, result in failure -- so there must be some element of the game and how it interacts with story that allows me to enjoy one in its entirety while feeling dissatisfied with the ending of the other.

Aha! It isn't the futile ending that is disappointing. It is the fact that the futile ending was not a part of game play -- it was a forced narrative tacked on to the end of the game. When the player inevitably loses in Robotron it is because the game has finally become too hard to finish, the game has literally beaten you. When you "lose" at the end of Dawn of War, it occurs after you have achieved "final victory." The contradiction lies in the interaction between the mechanics and the story -- a contradiction made even stronger by the underlying expectations of Real Time Strategy games. The underlying expectation of an RTS is that you can win, any advantage in supply or troops the computer opponent has is usually made up by an imperfect AI -- necessarily imperfect as a perfect AI would likely win all the time and lessen the fun.

Would I have felt differently if I had actually lost the final scenario of Dawn of War rather than have a scripted 70s ending? Not if the game had followed standard RTS genre conventions, the player "must" have a chance to win in the conventional. If the game progressed in a manner similar to other RTS games, each level getting slightly more difficult but winnable, with a final impossible level, the game would have likely been as unsatisfactory. This dissatisfaction would likely have been accentuated by the interstitial narrative clips.

On the other hand, if the game lacked interstitial clips and the narrative left only to game play I would probably have accepted an unwinnable level. At least possibly, especially if I knew going in that the game eventually becomes unwinnable as each level becomes more difficult than the last. But that isn't the central conceit of an RTS campaign, the central conceit of an RTS campaign is that the player is unlocking a heroic narrative. In this case, each victory leads to a new chapter in the hero's tale. A hero can hit a low point, like the one at the end of Dawn of War, but that ought not be the end of the story. In this case, it is. There is no sequel to the narrative, though there are many sequels to the game. My Blood Angels forever stand defeated in their victory, where my mutant defender of humanity just ends up dead after finally facing overwhelming odds.

I think it would be interesting for someone to design an RTS where each level becomes more difficult than the last, with no end in sight. Then the story changes from how my victory was taken from me, to how far I was able to get and who is able to get to the farthest level. I think I might prefer traditional RTS games -- with victorious endings -- to that "futile" RTS, but given my love of Robotron 2084 I'd probably like that killer RTS more than the end of Dawn of War because the ending would be driven by the mechanics of the game.

I don't mind losing when it's a part of the rules, but I hate losing when I won fair and square.

At the San Diego Comic Con this year, I asked Jeff Tidball if he would allow me to write a series of posts featuring the statements from the book. Each blog post would be a gamer reacting to one of the statements in the book, and eventually I'd like to address all the statements made by the various game designers. I will also continually belabor the fact that Will and Jeff asked Wil Wheaton, and not me, to write the introduction to the book. While this is a common mistake, it is one that I will point out at every opportunity. Yes, Wheaton is more famous (and is in Secret of Nimh which I recommended as last week's Hulu recommendation), but I am less likely to use expletives.

This being a blog, and not a Thesis or Dissertation, I will address the statements in no particular order, but I do hope to address them all. Today's blog topic is inspired by the 101st entry in the book.

STATEMENT 101

Know Why You Play Games.

The statement is simple enough, and is a gamer's version of Oracle of Delphi's famous dictum Gnōthi sauton or "Know Thyself." It is a statement seems to have an underlying claim that some ludophile Socrates might adhere to, "the unexamined gaming experience isn't worth playing." That may, in one way, be the whole point of Hindmarch's and Tidball's book, but this quote provides a nice starting point for any discussion regarding games and spurs one on to think philosophically about the subject.

It was this thought that was lurking around my subconscious when I read an article at Gamasutra about Robotron 2084. The article is an historical article about the game and its legacy with regard to game play. A good amount of time is spent discussing the games innovative use of a two joystick system, an innovation that couldn't be accurately emulated in a "home experience" for many years. It makes for interesting reading, but there was one quote which mixed with STATEMENT 101 to inspire me to think about why I play games. The quote was a simple one, "The player is tasked with the grim, desperate, and ultimately futile task of saving the last family of Humanoids (emphasis added)."

Ultimately futile -- the words echoed in the back of my mind.

Why would I want to play a game that I cannot, no matter how skilled I get at it, "win?"

What particularly bothered me about this statement is that it pointed to a contradiction in my game playing habits. I have been a fan of Robotron 2084 for decades and have played it uncountable times. In that time my skill level has migrated, from poor to excellent to poor to average, depending on how often I have played the game during a given time period. I am not always in the mood for Robotron, but I never find the game -- as it was designed -- to be a bad game. As big a fan as I am of this particular futile effort, I was seriously disappointed by the end of Dawn Of War

The futility of all my hard work playing Dawn of War was made clear to me during the final animated narrative sequence. Lucien Soulban's scripted ending undid everything I had struggled for in playing the game -- and it seriously aggravated me. I was all the more aggravated because an author/game designer I respect was the one who dropped the "futility bomb" on my head.

Why was I experiencing such a strong emotion that was, on its face, a contradictory sentiment to my thorough enjoyment of the equally futile Robotron 2084? To answer this, it was helpful to contemplate statement 101.

Why do I play games?

I play different games for a variety of reasons, but one reason that keeps me coming back is "story." I like the way that games, of all kinds, tell stories. It's one of the reasons I am a "good loser." I don't mind losing to someone who is better than me at Chess, all I want is my learning experience to be a good story. Candyland, with its pre-determined gameplay, taught me the importance of story in play and de-emphasized "winning." Both Robotron 2084 and Dawn of War contain story elements. Robotron's appear to be "weak" at first, but they are deeply embedded in gameplay -- if simple narratively. Both games contain narratives where the actions of the player, in the end, result in failure -- so there must be some element of the game and how it interacts with story that allows me to enjoy one in its entirety while feeling dissatisfied with the ending of the other.

Aha! It isn't the futile ending that is disappointing. It is the fact that the futile ending was not a part of game play -- it was a forced narrative tacked on to the end of the game. When the player inevitably loses in Robotron it is because the game has finally become too hard to finish, the game has literally beaten you. When you "lose" at the end of Dawn of War, it occurs after you have achieved "final victory." The contradiction lies in the interaction between the mechanics and the story -- a contradiction made even stronger by the underlying expectations of Real Time Strategy games. The underlying expectation of an RTS is that you can win, any advantage in supply or troops the computer opponent has is usually made up by an imperfect AI -- necessarily imperfect as a perfect AI would likely win all the time and lessen the fun.

Would I have felt differently if I had actually lost the final scenario of Dawn of War rather than have a scripted 70s ending? Not if the game had followed standard RTS genre conventions, the player "must" have a chance to win in the conventional. If the game progressed in a manner similar to other RTS games, each level getting slightly more difficult but winnable, with a final impossible level, the game would have likely been as unsatisfactory. This dissatisfaction would likely have been accentuated by the interstitial narrative clips.

On the other hand, if the game lacked interstitial clips and the narrative left only to game play I would probably have accepted an unwinnable level. At least possibly, especially if I knew going in that the game eventually becomes unwinnable as each level becomes more difficult than the last. But that isn't the central conceit of an RTS campaign, the central conceit of an RTS campaign is that the player is unlocking a heroic narrative. In this case, each victory leads to a new chapter in the hero's tale. A hero can hit a low point, like the one at the end of Dawn of War, but that ought not be the end of the story. In this case, it is. There is no sequel to the narrative, though there are many sequels to the game. My Blood Angels forever stand defeated in their victory, where my mutant defender of humanity just ends up dead after finally facing overwhelming odds.

I think it would be interesting for someone to design an RTS where each level becomes more difficult than the last, with no end in sight. Then the story changes from how my victory was taken from me, to how far I was able to get and who is able to get to the farthest level. I think I might prefer traditional RTS games -- with victorious endings -- to that "futile" RTS, but given my love of Robotron 2084 I'd probably like that killer RTS more than the end of Dawn of War because the ending would be driven by the mechanics of the game.

I don't mind losing when it's a part of the rules, but I hate losing when I won fair and square.

Friday, April 02, 2010

The 2010 Origins Awards Examined Part 2 -- Children's, Family, or Party Game

Tuesday, I gave a list of all the nominees for this year's Origin Awards -- the Hobby Gaming Oscars -- and included some closer examination of two of the categories. I was impressed with all the Card Game and Board Game nominees, but it was probably pretty clear that a couple of them held particularly special places in my heart. As I mentioned in the previous post, the Origin Awards (Awarded in June at GAMA's Origins gaming convention) are the gaming hobby equivalent of the Academy Award. Technically, the Origins award is the official award of the "Academy of Adventure Gaming Arts & Design." The Academy is made up of both professional and hobbyists, and the nominee selection process has participation at the hobbyist, professional designer, and retail distribution levels.

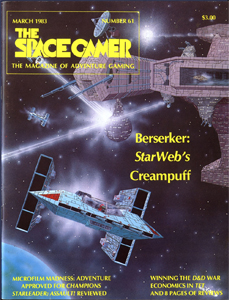

This has been true for quite some time, and the public/industry nature of the award is one of its great strengths. Looking back at a February 1982 issue of The Space Gamer (one of the leading gaming hobby magazines of the 1980s) one finds a nomination ballot soliciting nominations from fandom at large -- a process that is not longer followed for a variety of reasons. In that ballot, the selection committee is described as follows, "An international Awards Committee of 25 hobbyists (some professionals, but primarily independents) directs and administers the awards system." I'll write more about the process in my post regarding the failure of some publishers to properly promote their work by submitting to the Juries this year in a future post. Suffice to say that the Academy is, and has always been, an organization of professionals and amateurs working together to ensure that the best in the hobby get proper consideration.

Today I'd like to take a look at another category. I'll be providing information about the Children's, Family, or Party Game nominees.

This has been true for quite some time, and the public/industry nature of the award is one of its great strengths. Looking back at a February 1982 issue of The Space Gamer (one of the leading gaming hobby magazines of the 1980s) one finds a nomination ballot soliciting nominations from fandom at large -- a process that is not longer followed for a variety of reasons. In that ballot, the selection committee is described as follows, "An international Awards Committee of 25 hobbyists (some professionals, but primarily independents) directs and administers the awards system." I'll write more about the process in my post regarding the failure of some publishers to properly promote their work by submitting to the Juries this year in a future post. Suffice to say that the Academy is, and has always been, an organization of professionals and amateurs working together to ensure that the best in the hobby get proper consideration.

Today I'd like to take a look at another category. I'll be providing information about the Children's, Family, or Party Game nominees.

Children’s, Family, or Party Game

As the Dice Tower review makes clear this game is a faster and more chaotic version of the traditional game Werewolf, a version that is significantly removed from the traditional game that inspired it. This is a game that has great potential for fun, or great potential for boredom depending on the group it is played with. One can imagine dynamic games where long conversation periods precede the accusation process, but one can also picture games where the accusations come so swiftly as to undermine the game play value. Typical of Looney Labs creations this game is very loose in structure and you need to consider the playing group that you are with before considering playing this game. One advantage this game has over traditional Werewolf games is that no players are ever eliminated from play. The winners of a round receive points and play moves on to the next round. This prevents any players from feeling left out as the game continues and is one of the great innovations in this adaptation.

Duck! Duck! SAFARI! is the latest in Ape Games duck! duck! series of games featuring a broad array of rubber ducky themed toys. SAFARI contains the rules and pieces for five different games, the rules for a sixth game have been added on the website, for players ages 6 and up. I am a fan of games like this, and Stonehenge, that offer gamers a decent bang for their gaming dollar. The package includes traditional race games and memory based games with excellent components. Besides, who isn't a sucker for things this cute?

Do you want all the panic and chaos of moving day, including wondering just how you are going to fit your giant library of games into the moving truck, without any of the back ache? Then Pack and Stack is the game for you. Mayfair Games has made a business of importing entertaining family games from Germany to the United States and this is yet another feather in their cap.

A few years back, Atlas Games released a wonderful little card game by the title Gloom which featured two wonderful game play innovations -- a requirement that to win you had to make the life of your opponent better than your own, and the use of translucent cards that layered effects on your base playing card. With Ren Faire designers Michelle Nephew and Wendy Wyman have found another way to create competitive play that doesn't feel competitive. Ren Faire is a game of Ren Faire noobs who are desperate to garb themselves in appropriate attire in order to fit in with the rest of the crowd. The game uses transparent cards to represent the clothing that will go upon your avatar, but to get those clothes you must play performance cards to earn the money to buy the clothes. This is where Nephew and Wyman's innovation comes in. Players must actually perform the actions described on the performance cards. This can lead to mayhem and amusement. Mechanically, this game is a perfect fit in Atlas Games line of non-rpgs. I have long considered their Once Upon a Time to be among the best games with regard to combining card games with performance, and now they have added another game to the list.

Ever since Out of the Box Games release their excellent Apples to Apples game, the company has been a leader in the independent Children's and Family game market. With Cineplexity, they demonstrated that they could make a movie trivia game with extraordinarily high replayability. Last year's release of Word on the Street once again demonstrates the company's ability to create trivia games with tremendous replay value. The goal of the game is to bring all of the letter tiles onto your side of the board by selecting a word based upon a category card, think Fact in Five, and pulling over every letter tile that the word contains one lane closer to your side. One twist, you have a time limit and when time is up you can no longer move tiles. You and your team must choose words that move the most tiles, but you must do so quickly and as the other team tries to distract you -- possibly by claiming that your word doesn't fit the category. Spend to much time defending the "legality" of your word and you might no move any tiles. The game combines elements of Scrabble, Boggle, and Apples to Apples to create an entertaining experience.

Thursday, May 31, 2018

A Look Back at CHAMPIONS 1st Edition.

With the recent announcement that Ron Edwards was teaming up with Hero Games to produce CHAMPIONS NOW, a game that hearkens back to the first three editions of the game, I thought it would be a good time to take a look at those older editions.

The CHAMPIONS super hero role playing game is one of the best super hero role playing games ever designed, and the game to which all super hero rpgs are compared. CHAMPIONS wasn't the first role playing game in the super hero genre, that honor goes to the game SUPERHERO 2044 which I discussed in an earlier blog post. CHAMPIONS even builds upon some of the ideas in SUPERHERO 2044. CHAMPIONS used the vague point based character generation system of SUPERHERO 2044 -- combined with house rules by Wayne Shaw that were published in issue 8 of the Lords of Chaos Fanzine-- as a jumping off point for a new detailed and easy to understand point based system. CHAMPIONS was also likely influenced by the melee combat system in SUPERHERO 2044 in the use of the 3d6 bell curve to determine "to-hit" rolls in combat.

While CHAMPIONS wasn't the first super hero rpg, it was the first that presented a coherent system that allowed a player to design the superheroes they read about in comic books. The first edition of VILLAINS & VIGILANTES, which predates CHAMPIONS, did a good job of emulating many aspects of comic book action but the ability to model a character in character design wasn't one of them. CHAMPIONS was released at the Origins convention in the summer of 1981, and it immediately captured the interest of Aaron Allston of Steve Jackson Games. Allston gave CHAMPIONS a positive review in issue #43 of the Space Gamer magazine, wrote many CHAMPIONS articles for that publication, and became one of the major contributors to the early days of CHAMPIONS lore.

Reading through the first edition of the game, can have that kind of effect upon a person. The writing is clear -- if uneven in places -- and the rules mechanics inspire a desire to play around in the sandbox provided by the rules. George MacDonald and Steve Peterson did more than create a great role playing game when they created CHAMPIONS, they created a great character generation game as well. Hours can be taken up just playing around with character concepts and seeing how they look in the CHAMPIONS system.

There are sites galore about CHAMPIONS and many reviews about how great the game is, and it truly is, so the remainder of the post won't be either of these. Rather, I would like to point out some interesting tidbits about the first edition of the game. Most of these will be critical in nature, but not all. Before going further I will say that though CHAMPIONS is now in its 6th edition and is a very different game today in some ways, the 1st edition of the game is highly playable and well worth exploring and I'm glad that Ron Edwards has picked up that torch with CHAMPIONS NOW.

This is an update of a post from 2012.

The CHAMPIONS super hero role playing game is one of the best super hero role playing games ever designed, and the game to which all super hero rpgs are compared. CHAMPIONS wasn't the first role playing game in the super hero genre, that honor goes to the game SUPERHERO 2044 which I discussed in an earlier blog post. CHAMPIONS even builds upon some of the ideas in SUPERHERO 2044. CHAMPIONS used the vague point based character generation system of SUPERHERO 2044 -- combined with house rules by Wayne Shaw that were published in issue 8 of the Lords of Chaos Fanzine-- as a jumping off point for a new detailed and easy to understand point based system. CHAMPIONS was also likely influenced by the melee combat system in SUPERHERO 2044 in the use of the 3d6 bell curve to determine "to-hit" rolls in combat.

While CHAMPIONS wasn't the first super hero rpg, it was the first that presented a coherent system that allowed a player to design the superheroes they read about in comic books. The first edition of VILLAINS & VIGILANTES, which predates CHAMPIONS, did a good job of emulating many aspects of comic book action but the ability to model a character in character design wasn't one of them. CHAMPIONS was released at the Origins convention in the summer of 1981, and it immediately captured the interest of Aaron Allston of Steve Jackson Games. Allston gave CHAMPIONS a positive review in issue #43 of the Space Gamer magazine, wrote many CHAMPIONS articles for that publication, and became one of the major contributors to the early days of CHAMPIONS lore.

Reading through the first edition of the game, can have that kind of effect upon a person. The writing is clear -- if uneven in places -- and the rules mechanics inspire a desire to play around in the sandbox provided by the rules. George MacDonald and Steve Peterson did more than create a great role playing game when they created CHAMPIONS, they created a great character generation game as well. Hours can be taken up just playing around with character concepts and seeing how they look in the CHAMPIONS system.

There are sites galore about CHAMPIONS and many reviews about how great the game is, and it truly is, so the remainder of the post won't be either of these. Rather, I would like to point out some interesting tidbits about the first edition of the game. Most of these will be critical in nature, but not all. Before going further I will say that though CHAMPIONS is now in its 6th edition and is a very different game today in some ways, the 1st edition of the game is highly playable and well worth exploring and I'm glad that Ron Edwards has picked up that torch with CHAMPIONS NOW.

- One of the first things that struck me reading the book was how obviously playtested the character design system was. This is best illustrated in the section under basic characteristics. In CHAMPIONS there are primary and secondary characteristics. The primary characteristics include things like Strength and Dexterity. The secondary statistics are all based on fractions of the primary statistics and represent things like the ability to resist damage. Where the playtesting shows here is in how players may buy down all of their primary statistics, but only one of their secondary statistics. A quick analysis of the secondary statistics demonstrates that if this were not the case a "buy strength then buy down all the secondary stats related to strength" infinite loop would occur.

- It's striking how few skills there are in 1st edition CHAMPIONS. There are 14 in total, and some of them are things like Luck and Lack of Weakness. There are no "profession" skills in 1st edition. To be honest, I kind of like the lack of profession skills. Professions in superhero adventures seem more flavor than something one should have to pay points for, but this is something that will change in future editions.

- There are a lot of powers in CHAMPIONS, but the examples are filled with phrases like "a character" or "a villain" instead of an evocative hero/villain name. It would have been more engaging for the folks at Hero Games to create some Iconic characters that are used throughout the book as examples of each power. The game does include 3 examples of character generation (Crusader, Ogre, and Starburst), but these characters aren't mentioned in the Powers section. An example using Starburst in the Energy Blast power would have been nice.

- The art inside the book is less than ideal. Mark "the hack" Williams has been the target of some criticism for his illustrations, but his work is the best of what is offered in the 1st edition book. It is clear why they decided to use his work in the 2nd edition of the game. Williams art is evocative and fun -- if not perfect -- while the work Vic Dal Chele and Diana Navarro is more amateurish.

- The game provides three examples of character generation, but the designs given are less than point efficient and one outclasses the others. The three sample characters are built on 200 points. Crusader can barely hurt Ogre if he decides to punch him (his punch is only 6 dice), and his Dex is bought at one point below where he would receive a rounding benefit. Ogre has a Physical Defense of 23. This is the amount of damage he subtracts from each physical attack that hits and it is very high. Assuming an average of 3.5 points of damage per die, Ogre can resist an average of 6.5 dice of damage per attack. Yes, that's an average but the most damage 6 dice could do to him would be 13. That would be fine, except Crusader has that 6d6 punch, and Starburst...oh, Starburst. All of Starburst's major powers are in a multipower which means that as he uses one power he can use less of the other powers in the multipower. The most damage he can do is 8d6, but only if he isn't flying and doesn't have his forcefield up. Not efficient at all. One might hope that character examples demonstrate the appropriate ranges of damage and defense, these don't quite achieve that goal.

- The combat example is good, if implausible. Crusader and Starburst defeating Ogre? Sure.

- The supervillain stats at the end of the book -- there are stats for 8 villains and 2 agents -- lack any accompanying art. The only exception is Shrinker.

- Speaking of artwork and iconics. Take that cover.

- Who are these people?! I want to know. The only one who is mentioned in the book is Gargoyle. It's pretty clear which character he is, but I only know his name because of a copyright notice. Who are the other characters? Is that "Flare"? The villain is named Holocaust, but that cannot be discerned from reading this rule book. If you know, please let me know. I'd love to see the stats for that guy punching "Holocaust" with his energy fist.

This is an update of a post from 2012.

Friday, May 28, 2010

Steve Jackson Games to Release OGRE 6th Edition Eventually

In 1977, Metagaming Concepts released the first game in their successful Microgames line of affordable war games -- it had a $2.95 cover price. The game had a reasonable print run of 8,000 copies and was a break out success that redefined the war gaming hobby by opening the door to new audiences of simulation game players. The game's second print run was 20,000. The game was among the first war games to have a science fiction theme, and it featured rules that were simple enough for someone who had never played a war game to pick up and play within minutes.

The game was titled OGRE and it was so successful a game that its sales fueled the development and growth of two hobby gaming corporations. The first company, Metagaming Concepts, fought hard to keep the intellectual property rights when the game's designer left the company to found his own company Steve Jackson Games. The lawsuit lasted for quite some time, but eventually the property followed its creator to its new home. By the time the game migrated over to Steve Jackson Games, it had sold approximately 70,000 copies (excluding the sales of its GEV expansion set).

It was the reliable sales of OGRE that provided the revenue which allowed Steve Jackson Games to publish their next runaway success -- a game so successful it made OGRE's sale look small by comparison. That game was Car Wars, but its story is a tale for another time. Today is a day to praise OGRE and to share our anticipation for the upcoming release of OGRE 6th Edition which should be released later this year.

The premise of OGRE is a simple one, but it is also one that captures the imagination. The OGRE referred to in the game is a cybernetic supertank that is attacking a human manned command center on a nuclear blasted battlefield. Inspired by Keith Laumer's Bolo series, Steve Jackson created a game where desperate -- and mortal -- defenders battle against the odds to preserve their fragile position against impossible odds. Though their forces significantly outnumber the OGRE, the supertank significantly outclasses them. The tone of the game can be readily seen in an article published in issue 9 of the venerable The Space Gamer magazine:

The command post was well guarded. It should have been. The hastily constructed, unlovely building was the nerve center for Paneuropean operations along a 700 kilometer section of front -- a front pressing steadily toward the largest Combine manufacturing center on the continent.

Therefore General DePaul had taken no chances. His command was located in the most defensible terrain available -- a battered chunk of gravel bounded on three sides by marsh and on the fourth by a river. The river was deep and wide; the swamp gluey and impassible. Nothing bigger than a rat could avoid detection by the icons scattered for 60 kilometers in every direction over land, swamp, and river surface. Even the air was finally secure; the enemy had expended at least 50 heavy missiles yesterday, leaving glowing holes over half the island, but none near the CP. The Combine's laser batteries had seen to that. Now that the jamscreen was up, nothing would get even that close. And scattered through the twilight were the bulky shapes of tanks and ground effect vehicles -- the elite 2033rd Armored, almost relaxed as they guarded a spot nothing could attack.

Inside the post, too, the mood was relaxed -- except at one monitor station, where a young lieutenant watched a computer map of the island. A light was blinking on the river. Orange: something was moving, out there where nothing should move. No heat. A stab at the keyboard called up a representation of the guardian unit...not that any should be out there, 30 kilometers away. None were. Whatever was out there was a stranger -- and it was actually in the river. A swimming animal? A man? Ridiculous.

The lieutenant spun a cursor, moving a dot of white light across the map and halting it on the orange spot with practiced ease. He hit another key, and an image appeared on the big screen...pitted ground, riverbank...and something else, something rising from the river like the conning tower of an old submarine, but he knew what it really was, he just couldn't place it...and then it moved. Not straight toward the camera icon, but almost. The lieutenant saw the "conning tower" cut a wake through the rushing water, bounce once, and begin to rise. A second before the whole shape was visible, he recognized it -- but for that second he was frozen. And so 30 men with their minds on other things were suddenly brought to heart-pounding alert, as the lieutenant's strangled gasp and the huge image on his screen gave the same warning...

OGRE!

Like the "Mayday!" on the Traveller role playing game box, this description has fired my imagination for years. The fear of the command post staff is palpable, but one can only truly understand their fear after playing the game. The OGRE is a killing machine that tears through defending infantry, ground effect vehicles, and heavy tanks alike. Sometimes one wonders if there is a way to stop the OGRE at all. Then one finds an "unbeatable" strategy that succeeds in defending a few command posts, only to find that the OGRE has adapted to the new strategies and once again exterminates those who stand in its way.

The original war game version of OGRE is a very strategically deep game, even more so when you add the Shockwave and GEV expansions, that has been printed in four "map and counter" editions and one Miniatures edition. The miniatures edition was printed in the 1990s and is a fun game, but I have always felt that it -- like the edition of Car Wars that came out at the beginning of this millennium -- was not the right direction for the game to go. I am certain the miniatures were profitable, and I believe that SJG should have made the miniatures game, but I think that SJG was wrong in thinking that the miniatures game had replaced the classic "map and counter" version of the game. It hadn't, not any more than Warhammer the role playing game replaced Warhammer the miniatures game. To be fair, SJG sold the games parallel in the 90s -- it wasn't until the early 00s that they marketed the miniatures game as a replacement. It just seems to me that OGRE's core strength is its accessibility, both in rules and in price point, and a miniatures game moves away from this strength.

OGRE has been on hiatus for a few years as SJG has focused the majority of their efforts on the wildly successful Munchkin card game. SJG has a history of focusing like a laser on their most successful titles while leaving less attention for other products.

But this year seems to be the year that SJG, after two years of excellent non-Munchkin offerings, is resurrecting the OGRE. The sixth edition of the game has components that fall somewhere between the map and counter game of old and the more recent miniatures game. This edition will feature "chipboard" playing pieces that the players construct for use in play. This is an approach that takes advantage of the cost savings of a "printed" rather than a "cast" product line, while having greater aesthetic appeal than looking at square counters bearing numbers.

I think it is the right direction for the game, and I hope that it is a successful venture for Steve Jackson Games.

I know that I am eagerly awaiting this edition and will proudly place it next to my OGRE/GEV boxed set, OGRE mini-game, OGRE Book (first and second editions), and OGRE Deluxe Edition (non-miniature) versions of the game.

If all goes well, I should be able to purchase and play the game at this year's GENCON -- though they don't include OGRE in their list of official releases yet.

Tuesday, October 16, 2012

[Vintage RPGs] CHAMPIONS 1st Edition -- A Blast from the Past

The CHAMPIONS super hero role playing game is one of the best super hero role playing games ever designed, and the game to which all super hero rpgs are compared. CHAMPIONS wasn't the first role playing game in the super hero genre, that honor goes to the game SUPERHERO 2044 which I discussed in an earlier blog post. CHAMPIONS even builds upon some of the ideas in SUPERHERO 2044. CHAMPIONS used the vague point based character generation system of SUPERHERO 2044 -- combined with house rules by Wayne Shaw -- as a jumping off point for a new detailed and easy to understand point based system. CHAMPIONS was also likely influenced by the melee combat system in SUPERHERO 2044 in the use of the 3d6 bell curve to determine "to-hit" rolls in combat.

While CHAMPIONS wasn't the first super hero rpg, it was the first that presented a coherent system by which a player could design the superheroes they read about in comic books. The first edition of VILLAINS & VIGILANTES, which predates CHAMPIONS, did a good job of emulating many aspects of comic book action but the ability to model a character in character design wasn't one of them. CHAMPIONS was released at the Origins convention in the summer of 1981, and it immediately captured the interest of Aaron Allston of Steve Jackson Games. Allston gave CHAMPIONS a positive review in issue #43 of the Space Gamer magazine, wrote many CHAMPIONS articles for that publication, and became one of the major contributors to the early days of CHAMPIONS lore.

Reading through the first edition of the game, as I have been doing the past week, can have that kind of effect upon a person. The writing is clear -- if uneven in places -- and the rules mechanics inspire a desire to play around in the sandbox provided by the rules. George MacDonald and Steve Peterson did more than create a great role playing game when they created CHAMPIONS, they created a great character generation game as well. Hours can be taken up just playing around with character concepts and seeing how they look in the CHAMPIONS system.

There are sites galore about CHAMPIONS and many reviews about how great the game is, and it truly is, so the remainder of the post won't be either of these. Rather, I would like to point out some interesting tidbits about the first edition of the game. Most of these will be critical in nature, but not all. Before going further I will say that though CHAMPIONS is now in its 6th edition and is a very different game today in some ways, the 1st edition of the game is highly playable and well worth exploring.

While CHAMPIONS wasn't the first super hero rpg, it was the first that presented a coherent system by which a player could design the superheroes they read about in comic books. The first edition of VILLAINS & VIGILANTES, which predates CHAMPIONS, did a good job of emulating many aspects of comic book action but the ability to model a character in character design wasn't one of them. CHAMPIONS was released at the Origins convention in the summer of 1981, and it immediately captured the interest of Aaron Allston of Steve Jackson Games. Allston gave CHAMPIONS a positive review in issue #43 of the Space Gamer magazine, wrote many CHAMPIONS articles for that publication, and became one of the major contributors to the early days of CHAMPIONS lore.

Reading through the first edition of the game, as I have been doing the past week, can have that kind of effect upon a person. The writing is clear -- if uneven in places -- and the rules mechanics inspire a desire to play around in the sandbox provided by the rules. George MacDonald and Steve Peterson did more than create a great role playing game when they created CHAMPIONS, they created a great character generation game as well. Hours can be taken up just playing around with character concepts and seeing how they look in the CHAMPIONS system.

There are sites galore about CHAMPIONS and many reviews about how great the game is, and it truly is, so the remainder of the post won't be either of these. Rather, I would like to point out some interesting tidbits about the first edition of the game. Most of these will be critical in nature, but not all. Before going further I will say that though CHAMPIONS is now in its 6th edition and is a very different game today in some ways, the 1st edition of the game is highly playable and well worth exploring.

- One of the first things that struck me reading the book was how obviously playtested the character design system was. This is best illustrated in the section under basic characteristics. In CHAMPIONS there are primary and secondary characteristics. The primary characteristics include things like Strength and Dexterity. The secondary statistics are all based on fractions of the primary statistics and represent things like the ability to resist damage. Where the playtesting shows here is in how players may buy down all of their primary statistics, but only one of their secondary statistics. A quick analysis of the secondary statistics demonstrates that if this were not the case a buy strength then buy down all the secondary stats related to strength infinite loop would occur.

- It's striking how few skills there are in 1st edition CHAMPIONS. There are 14 in total, and some of them are thinks like Luck and Lack of Weakness. There are no "profession" skills in 1st edition. To be honest, I kind of like the lack of profession skills. Professions in superhero adventures seem more flavor than something one should have to pay points for, but this is something that will change in future editions.

- There are a lot of powers in CHAMPIONS, but the examples are filled with phrases like "a character" or "a villain" instead of an evocative hero/villain name. It would have been more engaging for the folks at Hero Games to create some Iconic characters that are used throughout the book as examples of each power. The game does include 3 examples of character generation (Crusader, Ogre, and Starburst), but these characters aren't mentioned in the Powers section. An example using Starburst in the Energy Blast power would have been nice.

- The art inside the book is less than ideal. Mark "the hack" Williams has been the target of some criticism for his illustrations, but his work is the best of what is offered in the 1st edition book. It is clear why they decided to use his work in the 2nd edition of the game. Williams art is evocative and fun -- if not perfect -- while the work Vic Dal Chele and Diana Navarro is more amateurish.

- The game provides three examples of character generation, but the designs given are less than point efficient and one outclasses the others. The three sample characters are built on 200 points. Crusader can barely hurt Ogre if he decides to punch him (his punch is only 6 dice), and his Dex is bought at one point below where he would receive a rounding benefit. Ogre has a Physical Defense of 23. This is the amount of damage he subtracts from each physical attack that hits and it is very high. Assuming an average of 3.5 points of damage per die, Ogre can resist an average of 6.5 dice of damage per attack. Yes, that's an average but the most damage 6 dice could do to him would be 13. That would be fine, except Crusader has that 6d6 punch, and Starburst...oh, Starburst. All of Starburst's major powers are in a multipower which means that as he uses one power he can use less of the other powers in the multipower. The most damage he can do is 8d6, but only if he isn't flying and doesn't have his forcefield up. Not efficient at all. One might hope that character examples demonstrate the appropriate ranges of damage and defense, these don't quite achieve that goal.

- The combat example is good, if implausible. Crusader and Starburst defeating Ogre? Sure.

- The supervillain stats at the end of the book -- there are stats for 8 villains and 2 agents -- lack any accompanying art. The only exception is Shrinker.

- Speaking of artwork and iconics. Take that cover.

- Who are these people?! I want to know. The only one who is mentioned in the book is Gargoyle. It's pretty clear which character he is, but I only know his name because of a copyright notice. Who are the other characters? Is that "Flare"? Someone once told me the villain's name was Holocaust, but that could just be a Bay Area rumor. If you know, please let me know. I'd love to see the stats for that guy punching "Holocaust" with his energy fist.

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

Sword and Skull -- A Boardgame Review in Honor of Talk Like a Pirate Day

Today is International Talk Like a Pirate Day in honor of which ABC's Wife Swap featured the Baur family last night (John Baur is a co-founder of Talk Like a Pirate Day). It is only fitting that on such an auspicious day we here at Cinerati should do a review of material related to pirates and piracy. One could easily do a positive review of Pirates for the PC/Xbox, but if you don't own the game you are no true pirate fan! It is a must have.

No...we here at Cinerati want to guide you into places you may not have looked before to be entertained, while at the same time not being so obscure as to be overly arcane and alienate the novice gamer. With that in mind, we would like to present the following review of the Sword and Skull boardgame published by Hasbro under their Avalon Hill label.

Sword and Skull is a simple "Track Game" for two to five players with an entertaining premise:

The nefarious Pirate King has stolen Her Majesty's Ship, the Sea Hammer, pride of the Royal Navy. Furious, the Queen has offered a great reward to the person who can retrieve it. As one of the advisors to the Queen, you have chosen an officer of the Royal Navy to pursue the Pirate King. Of course, it might take a thief to catch a thief, so you've also conscripted a vicioius pirate from the Queen's dungeons.

Now they are preparing to enter the dreaded Lair of the Pirate King. Will one of them be the first to recover the Sea Hammer? Or will one of your rivals receive the Queen's reward instead?

Each player in the game is in control of two "Avatars," one Pirate and one Loyal Captain, who must find a way to bring the Sea Hammer back to the Queen. There are two ways to achieve this goal. The player can either raise enough gold to bribe the Pirate King to return the ship, or the player can defeat the Pirate King in combat forcing him to return the ship. The goals may be simple, but the accomplishing of them is not for it is good to be the Pirate King. Player's start out with little money and even less skill at arms. So each player must work their way around the track encountering various fortunes/dangers until they have sufficient lucre or puissance to attain the goal.

The "track" element of the game requires the players to move around the track in a clockwise fashion and encounter the "space." This element of the game is like a combination of Monopoly and Games Workshop's famous questing game Talisman. Sword and Skull at the same time lacks the complexity of either the games it borrows from, and adds innovation to each. It is an interesting paradox, but one that is true. As the players work around the board (pictured below), they encounter various "space" types. The two most common are "settlements" and "caves."

At settlement squares the player can recruit crew to assist in the defeat of the Pirate king. These crew members are an absolute necessity and come in three types. "Money grinders," which are similar to property in Monopoly, provide the player with gold each time another player lands on a settlement matching the color of the money grinder and everytime the player passes the fort (think Go in Monopoly. What separates money grinders from property is that only the color of space matters and not the specific name of the individual square. Some settlements have three or four squares and if you have a money grinder for the settlement you are paid by the player landing their. Naturally, multiple players may have grinders at the same settlements. The second type of character is the "buffer" who adds combat skill to either your Navy Captain or your Pirate Captain (this is distinguished by a symbol on the card). Finally, there are crew who are both money grinders and buffers. Recruiting the right crew can lead to rapid victory, but it can also irritate other players.

At caves players encounter various "monsters." These range from the simple Crocodile to Pirate Skeletons. This type of encounter is nothing surprising to your average "quest game" fan, but they have added an innovation. The difficulty of defeating each challange is based on the size of your crew, your total crew. So if your Pirate Captain has to battle a Siren and you have 6 crew members you will have a tough challenge. This is especially true if all 6 of your crew are money grinders or Navy Captain buffers. So it helps to have a balanced crew. Defeating challenges gets you items and gold, items usually help you in combat and gold helps the bribe victory.

The games that I have played were fast and furious. The rules were clear enough that any inter-player bickering was due to cards which allow one player to "steal" items from another player (note: while this adds variety to games it can add "meanness"). The end game was close and all players had a chance to win during the last stages of the game. The game is simple and combines elements from board game classics. Of the two possible victory outcomes, the most rewarding seems to be combatting the Pirate King. This is true even though the more innovative of the two is to win by bribery. At the beginning of the game everyone knows how tough the Pirate King is, but no one knows how much it will take to bribe him until the end of the game.

Click on Photo of Game Box for PDF copy of the rules from the Hasbro site.

Click on Photo of Game Box for PDF copy of the rules from the Hasbro site.

No...we here at Cinerati want to guide you into places you may not have looked before to be entertained, while at the same time not being so obscure as to be overly arcane and alienate the novice gamer. With that in mind, we would like to present the following review of the Sword and Skull boardgame published by Hasbro under their Avalon Hill label.

Sword and Skull is a simple "Track Game" for two to five players with an entertaining premise:

The nefarious Pirate King has stolen Her Majesty's Ship, the Sea Hammer, pride of the Royal Navy. Furious, the Queen has offered a great reward to the person who can retrieve it. As one of the advisors to the Queen, you have chosen an officer of the Royal Navy to pursue the Pirate King. Of course, it might take a thief to catch a thief, so you've also conscripted a vicioius pirate from the Queen's dungeons.

Now they are preparing to enter the dreaded Lair of the Pirate King. Will one of them be the first to recover the Sea Hammer? Or will one of your rivals receive the Queen's reward instead?

Each player in the game is in control of two "Avatars," one Pirate and one Loyal Captain, who must find a way to bring the Sea Hammer back to the Queen. There are two ways to achieve this goal. The player can either raise enough gold to bribe the Pirate King to return the ship, or the player can defeat the Pirate King in combat forcing him to return the ship. The goals may be simple, but the accomplishing of them is not for it is good to be the Pirate King. Player's start out with little money and even less skill at arms. So each player must work their way around the track encountering various fortunes/dangers until they have sufficient lucre or puissance to attain the goal.

The "track" element of the game requires the players to move around the track in a clockwise fashion and encounter the "space." This element of the game is like a combination of Monopoly and Games Workshop's famous questing game Talisman. Sword and Skull at the same time lacks the complexity of either the games it borrows from, and adds innovation to each. It is an interesting paradox, but one that is true. As the players work around the board (pictured below), they encounter various "space" types. The two most common are "settlements" and "caves."

At settlement squares the player can recruit crew to assist in the defeat of the Pirate king. These crew members are an absolute necessity and come in three types. "Money grinders," which are similar to property in Monopoly, provide the player with gold each time another player lands on a settlement matching the color of the money grinder and everytime the player passes the fort (think Go in Monopoly. What separates money grinders from property is that only the color of space matters and not the specific name of the individual square. Some settlements have three or four squares and if you have a money grinder for the settlement you are paid by the player landing their. Naturally, multiple players may have grinders at the same settlements. The second type of character is the "buffer" who adds combat skill to either your Navy Captain or your Pirate Captain (this is distinguished by a symbol on the card). Finally, there are crew who are both money grinders and buffers. Recruiting the right crew can lead to rapid victory, but it can also irritate other players.

At caves players encounter various "monsters." These range from the simple Crocodile to Pirate Skeletons. This type of encounter is nothing surprising to your average "quest game" fan, but they have added an innovation. The difficulty of defeating each challange is based on the size of your crew, your total crew. So if your Pirate Captain has to battle a Siren and you have 6 crew members you will have a tough challenge. This is especially true if all 6 of your crew are money grinders or Navy Captain buffers. So it helps to have a balanced crew. Defeating challenges gets you items and gold, items usually help you in combat and gold helps the bribe victory.

The games that I have played were fast and furious. The rules were clear enough that any inter-player bickering was due to cards which allow one player to "steal" items from another player (note: while this adds variety to games it can add "meanness"). The end game was close and all players had a chance to win during the last stages of the game. The game is simple and combines elements from board game classics. Of the two possible victory outcomes, the most rewarding seems to be combatting the Pirate King. This is true even though the more innovative of the two is to win by bribery. At the beginning of the game everyone knows how tough the Pirate King is, but no one knows how much it will take to bribe him until the end of the game.

Click on Photo of Game Box for PDF copy of the rules from the Hasbro site.

Click on Photo of Game Box for PDF copy of the rules from the Hasbro site.

Monday, September 19, 2005

Swords and Skulls --- A Boardgame Review in Honor of Talk Like a Pirate Day

As was mentioned in a previous post, today is International Talk Like a Pirate Day. It is only fitting that on such an auspicious day we here at Cinerati should do a review of material related to pirates and piracy. One could easily do a positive review of Pirates for the PC/Xbox, but if you don't own the game you are no true pirate fan! It is a must have.

No...we here at Cinerati want to guide you into places you may not have looked before to be entertained, while at the same time not being so obscure as to be overly arcane and alienate the novice gamer. With that in mind, we would like to present the following review of the Sword and Skull boardgame published by Hasbro under their Avalon Hill label.

Sword and Skull is a simple "Track Game" for two to five players with an entertaining premise:

The nefarious Pirate King has stolen Her Majesty's Ship, the Sea Hammer, pride of the Royal Navy. Furious, the Queen has offered a great reward to the person who can retrieve it. As one of the advisors to the Queen, you have chosen an officer of the Royal Navy to pursue the Pirate King. Of course, it might take a thief to catch a thief, so you've also conscripted a vicioius pirate from the Queen's dungeons.

Now they are preparing to enter the dreaded Lair of the Pirate King. Will one of them be the first to recover the Sea Hammer? Or will one of your rivals receive the Queen's reward instead?

Each player in the game is in control of two "Avatars," one Pirate and one Loyal Captain, who must find a way to bring the Sea Hammer back to the Queen. There are two ways to achieve this goal. The player can either raise enough gold to bribe the Pirate King to return the ship, or the player can defeat the Pirate King in combat forcing him to return the ship. The goals may be simple, but the accomplishing of them is not for it is good to be the Pirate King. Player's start out with little money and even less skill at arms. So each player must work their way around the track encountering various fortunes/dangers until they have sufficient lucre or puissance to attain the goal.

The "track" element of the game requires the players to move around the track in a clockwise fashion and encounter the "space." This element of the game is like a combination of Monopoly and Games Workshop's famous questing game Talisman. Sword and Skull at the same time lacks the complexity of either the games it borrows from, and adds innovation to each. It is an interesting paradox, but one that is true. As the players work around the board (pictured below), they encounter various "space" types. The two most common are "settlements" and "caves."

At settlement squares the player can recruit crew to assist in the defeat of the Pirate king. These crew members are an absolute necessity and come in three types. "Money grinders," which are similar to property in Monopoly, provide the player with gold each time another player lands on a settlement matching the color of the money grinder and everytime the player passes the fort (think Go in Monopoly. What separates money grinders from property is that only the color of space matters and not the specific name of the individual square. Some settlements have three or four squares and if you have a money grinder for the settlement you are paid by the player landing their. Naturally, multiple players may have grinders at the same settlements. The second type of character is the "buffer" who adds combat skill to either your Navy Captain or your Pirate Captain (this is distinguished by a symbol on the card). Finally, there are crew who are both money grinders and buffers. Recruiting the right crew can lead to rapid victory, but it can also irritate other players.

At caves players encounter various "monsters." These range from the simple Crocodile to Pirate Skeletons. This type of encounter is nothing surprising to your average "quest game" fan, but they have added an innovation. The difficulty of defeating each challange is based on the size of your crew, your total crew. So if your Pirate Captain has to battle a Siren and you have 6 crew members you will have a tough challenge. This is especially true if all 6 of your crew are money grinders or Navy Captain buffers. So it helps to have a balanced crew. Defeating challenges gets you items and gold, items usually help you in combat and gold helps the bribe victory.

The games that I have played were fast and furious. The rules were clear enough that any inter-player bickering was due to cards which allow one player to "steal" items from another player (note: while this adds variety to games it can add "meanness"). The end game was close and all players had a chance to win during the last stages of the game. The game is simple and combines elements from board game classics. Of the two possible victory outcomes, the most rewarding seems to be combatting the Pirate King. This is true even though the more innovative of the two is to win by bribery. At the beginning of the game everyone knows how tough the Pirate King is, but no one knows how much it will take to bribe him until the end of the game.

Click on Photo of Game Box for PDF copy of the rules from the Hasbro site.

Click on Photo of Game Box for PDF copy of the rules from the Hasbro site.

No...we here at Cinerati want to guide you into places you may not have looked before to be entertained, while at the same time not being so obscure as to be overly arcane and alienate the novice gamer. With that in mind, we would like to present the following review of the Sword and Skull boardgame published by Hasbro under their Avalon Hill label.

Sword and Skull is a simple "Track Game" for two to five players with an entertaining premise:

The nefarious Pirate King has stolen Her Majesty's Ship, the Sea Hammer, pride of the Royal Navy. Furious, the Queen has offered a great reward to the person who can retrieve it. As one of the advisors to the Queen, you have chosen an officer of the Royal Navy to pursue the Pirate King. Of course, it might take a thief to catch a thief, so you've also conscripted a vicioius pirate from the Queen's dungeons.

Now they are preparing to enter the dreaded Lair of the Pirate King. Will one of them be the first to recover the Sea Hammer? Or will one of your rivals receive the Queen's reward instead?

Each player in the game is in control of two "Avatars," one Pirate and one Loyal Captain, who must find a way to bring the Sea Hammer back to the Queen. There are two ways to achieve this goal. The player can either raise enough gold to bribe the Pirate King to return the ship, or the player can defeat the Pirate King in combat forcing him to return the ship. The goals may be simple, but the accomplishing of them is not for it is good to be the Pirate King. Player's start out with little money and even less skill at arms. So each player must work their way around the track encountering various fortunes/dangers until they have sufficient lucre or puissance to attain the goal.

The "track" element of the game requires the players to move around the track in a clockwise fashion and encounter the "space." This element of the game is like a combination of Monopoly and Games Workshop's famous questing game Talisman. Sword and Skull at the same time lacks the complexity of either the games it borrows from, and adds innovation to each. It is an interesting paradox, but one that is true. As the players work around the board (pictured below), they encounter various "space" types. The two most common are "settlements" and "caves."

At settlement squares the player can recruit crew to assist in the defeat of the Pirate king. These crew members are an absolute necessity and come in three types. "Money grinders," which are similar to property in Monopoly, provide the player with gold each time another player lands on a settlement matching the color of the money grinder and everytime the player passes the fort (think Go in Monopoly. What separates money grinders from property is that only the color of space matters and not the specific name of the individual square. Some settlements have three or four squares and if you have a money grinder for the settlement you are paid by the player landing their. Naturally, multiple players may have grinders at the same settlements. The second type of character is the "buffer" who adds combat skill to either your Navy Captain or your Pirate Captain (this is distinguished by a symbol on the card). Finally, there are crew who are both money grinders and buffers. Recruiting the right crew can lead to rapid victory, but it can also irritate other players.

At caves players encounter various "monsters." These range from the simple Crocodile to Pirate Skeletons. This type of encounter is nothing surprising to your average "quest game" fan, but they have added an innovation. The difficulty of defeating each challange is based on the size of your crew, your total crew. So if your Pirate Captain has to battle a Siren and you have 6 crew members you will have a tough challenge. This is especially true if all 6 of your crew are money grinders or Navy Captain buffers. So it helps to have a balanced crew. Defeating challenges gets you items and gold, items usually help you in combat and gold helps the bribe victory.

The games that I have played were fast and furious. The rules were clear enough that any inter-player bickering was due to cards which allow one player to "steal" items from another player (note: while this adds variety to games it can add "meanness"). The end game was close and all players had a chance to win during the last stages of the game. The game is simple and combines elements from board game classics. Of the two possible victory outcomes, the most rewarding seems to be combatting the Pirate King. This is true even though the more innovative of the two is to win by bribery. At the beginning of the game everyone knows how tough the Pirate King is, but no one knows how much it will take to bribe him until the end of the game.

Click on Photo of Game Box for PDF copy of the rules from the Hasbro site.

Click on Photo of Game Box for PDF copy of the rules from the Hasbro site.

Tuesday, April 03, 2012

[Gaming History] Starleader: Assault! and Publisher vs. Creator Squabbles

Gamers who have only experienced the "edition wars" of the modern era might believe that the story of how Paizo Publishing became successful as a role playing game company is a unique occurrence. After all, it isn't every day that a major role playing game publisher decides to make some internal changes and those changes provide a perfect opportunity for a new game publisher to secure a market segment releasing a revised version of the older company's game.

In the case of Wizards of the Coast, their creation of the Open Gaming License, combined with their decision to abandon Dungeons & Dragons 3.5 in order to produce a 4th edition of the game, provided a perfect opportunity for Paizo Publishing to release the Pathfinder Role Playing Game. Those who played 3.5 know that Pathfinder is an update of the earlier Wizards of the Coast game, that features various improvements based on playtesting, an update that was much demanded by fans who felt abandoned by Wizards of the Coast for a variety of reasons. Not only was Paizo filled with talented game designers who understood the 3.5 edition of D&D, many of those same designers worked for Wizards at one time or another. In fact, many of Wizards most talented former game designers worked on the Pathfinder game. To state what happened in a very reductive manner (that isn't exactly true but is useful for illustrative purposes), Paizo effectively secured a market segment by releasing a product that a competitor had abandoned or improperly developed.

Paizo's rise as a major publisher in the industry is very interesting. I'm a big fan of their products, I was a first wave "Superscriber" of their merchandise, and I am a fan of Wizards of the Coast's 4th edition game. As a fan, I didn't pick sides in the fight. Many did. I am also a long time gamer who has been playing role playing games for over 20 years, and who has an obsessive desire to study the hobby and learn its history.