In 1977, Simulations Publications Inc. (SPI) published a booked entitled

Wargame Design: The History, Production, and Use of Conflict Simulation Games. This book is one of the great artifacts of the wargaming hobby and is an invaluable resource that provides accurate historical information about the state of the wargaming industry up to 1977. At that time, SPI had unit sales of 420,000 games a year to an audience of approximately 100,000-150,000 active gamers (Dunnigan, 140). The average cost of a war game at the time was $8 (in 1977 dollars), meaning that SPI had approximately $3.36 million in annual sales. According to the

Bureau of Labor Statistics, this is about $12,272,400 in 2011 dollars.

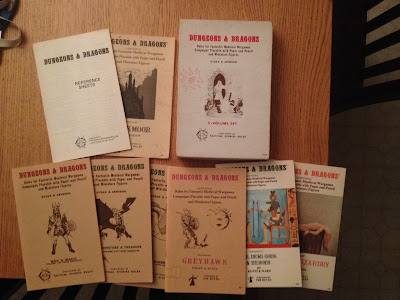

By any standard, SPI was a big business in a small market -- they held a 50% market share by units sold and a 43% market share in percentage of cash spent by gamers. But 1977 was a time of massive transitions in the industry. At that time 10% of wargamers were "miniature" gamers -- in addition to being general wargamers -- though given the cost of miniatures and supplies, these individuals made up 30% of the money spent on war games. This was also the time of the rise of a new kind of game, the fantasy role playing game. 1974 had seen the publication of the first printed role playing game,

Dungeons and Dragons, and that game was altering the gaming landscape forever.

Roleplaying games expanded the gaming market from the small community of 100,000-150,000 gamers, to a community of millions of gamers. By 2000, there were over 2 million people playing table top role playing games on

a monthly basis. Modern sales figures for individual role playing game companies are nigh impossible to find. The revenues are either unpublished -- because the majority of the companies are privately owned -- or they are buried in consolidated reports like Hasbro's annual report. Chris Pramas estimated that the RPG industry had annual sales in the

$30 million range in 2008. That number seems off by a wide margin for a couple of reasons. First, that would mean that the RPG industry is about the size of the wargame industry in 1977, which means that all the growth in the market since 1977 has collapsed -- assuming inflation adjusted dollars the market in 1977 was approximately $25 million. Second, according to their financials, Games Workshop -- a major fantasy miniatures gaming company --

reported £126.5 million in revenue in 2010. This signals that miniatures gaming has exploded since 1977 as a part of the market. One imagines that role playing games lag behind the miniatures market by a significant margin, but this hints that the market may be larger than Pramas fears. There are currently 49,983 members of Wizards of the Coast's "DDI Subscriber Group" which is a good estimate of the number of people who are subscribers to the site's functions. These subscriptions alone provide somewhere around $5 million in revenue. It is likely that the majority of these subscribers have purchased physical products in the year as well. I would guess that the entire rpg market is somewhere skyward of $50 million -- a little better than Pramas' guess. At least, I hopes so because a lower figure would mean that his company Green Ronin -- who publish a number of the best games in the market -- are tragically under appreciated by the market. Needless to say, the market has expanded as these figures don't include the modern war game market -- which is probably similar in size to the 1977 market -- the board game market (

Settlers of Catan alone has sold more than 18 million copies), trading card games, or computer rpgs. All of these are descendants of the old wargaming market place.

For the most part, SPI was a smart company and realized that the market was in flux and that these newfangled role playing games and miniatures games were where the market was headed. They gathered together some of their best and brightest game designers (Eric Goldberg, David James Ritchie, Edward J. Woods, Greg Costikyan, and Redmond A. Simonsen) and produced their own role playing game. The resulting product,

DragonQuest was published in 1980 with much fanfare, but less than stellar reviews.

[15.2]A character who is adjacent to, but not in the Attack Zone of, a Hostile character may employ actions A, B, C, D, E, F, H, J, L, M, P, Q, R, S, T, or X.

He could not implement Action G or W. Further, while he could Fire, he could not Fire at an adjacent character. He could also Hurl a weapon, but, again, not at an adjacent character. -- DragonQuest First Edition pg. 20 Rule 15.2

Forrest Johnson reviewing the game for in Space Gamer magazine, had the following to say:

"1.784 DESIGN IN HASTE, REPENT AT LEISURE. With all its talented staff, SPI has managed to do what companies like TSR and Metagaming did with lesser resources -- mess up a promising new system...DRAGONQUEST is not your dream game, And appearing in 1980, it is at a competitive disadvantage. But it was put together by professionals. Despite its faults, it still presents a pleasing contrast to the sloppiness of TFT, the illogic of D&D, the incoherence of C&S. It borrows good ideas liberally from the older systems, and offers some new innovatiosn of its own. Furthermore, the planned supplements, if only half of them see print, will make this an incredibly rich game."

The Chaosium affiliated magazine

Different Worlds in its 11th issue wrote that the game, "functions as a FRP game the same way a sledge hammer functions as a mousetrap. Both get the job done, but the effort involved in getting it to work is not worth the end result." This review prompted a response from designer Eric Goldberg which stated, "while mice have escaped from conventional mousetraps, none have survived being spattered about by a sledgehammer."

SPI published the combat rules for

DragonQuest as a stand alone game entitled

Arena of Death in SPI's in house

Ares magazine in its 4th issue and later as a stand alone boxed game. The first edition combat rules were bogged down by the fact that the rules structure and design was modeled after traditional war game presentations and not on the more narrative presentation of role playing games. As such, the combat rules were difficult to understand and very mechanical in play.

DragonQuest included many innovations in its magic system and its skill system, as well as its universal attribute test system, but the combat system of the first edition was arcane and overly complex. SPI quickly responded to the need to improve the game and released a second edition in 1981 -- one year after the original. One name stands out among those added to the list of "Game Testing and Advice," that I believe made all the difference in the world. That name is Greg Gorden. Gorden is one of the best designers in the business, and the changes between the two editions -- in addition to seeing Gorden's later work -- lead me to believe he was a major influence in the second edition.

[15.2]Figures with a modified Agility of 22 through 25 are allowed one extra hex of movement when executing any of the following actions: Melee attack, Evade, Withdraw, Pass, and Retreat.

Thus Eaglewing the Elf, whose modified Agility is 25 due to the lack of weight he carried, his natural Agility and his bonus due to being an Elf can move three hexes while preparing his Tulwar instead of two. -- DragonQuest 2nd Edition page 16 rule [15.2]

The second edition of the game kept all of the interesting quirks of the first edition, but cleaned up the play of the combat system -- and made some other minor tweaks as well. It also added images of miniatures in use during play and clearer examples of game play. The game seemed ready to take the market by storm. But then TSR -- the publishers of D&D -- purchased SPI on March 31, 1982. With that purchase support for

DragonQuest was minimal at best as TSR focused on their own games instead of the old SPI games. There were about 6 articles supporting

DragonQuest published in

Dragon magazine, but the "rumored" 4th rule book for the game

Arcane Wisdom never hit the stands. It wasn't just TSR's lack of interest in

DragonQuest that led to the lack of support. It was also the fact that when TSR bought SPI, most of the key SPI designers left the company to work for a new company called Victory Games. Gerard Klug, John Butterfield, and Greg Gorden all went to work for the new company. Within a year of their leaving TSR/SPI for Victory Games, these designers created the

James Bond 007 role playing game which built on some concepts presented in

DragonQuest, but completely abandoned the old school war game rules presentation.

TSR eventually published a cleaned up and revised 3rd edition of

DragonQuest in 1989, but for all of the improvements it made to the mechanics of the game it lost some of the flair of the original. Gone was the "College of Greater Summonings" with its demon bound magicians, and in was a lighter tone similar to many of the "Culture Wars scared" products TSR was publishing at the time. The 3rd edition is a good rules set, but if you're going to play the game you should also have a copy of the 2nd edition. The rich feel of the game's magical colleges is one of the best features of the game.

DragonQuest isn't without a literary legacy either.

James Barclay's "Raven" stories are based on his own

DragonQuest campaign.