The Preamble

Like many fans of genre fiction, mystery and suspense fiction in particular, I was excited to watch the new Perry Mason series on HBO. I really enjoyed the series and found that for me the episodes could not be released fast enough. In an era where streaming services like Netflix drop entire seasons of shows, having to wait a week to watch the next episode of a show can add a kind of excited tension to a show. This was certainly true for me with the new Perry Mason show, a show which provided an interesting mystery with rich characters.

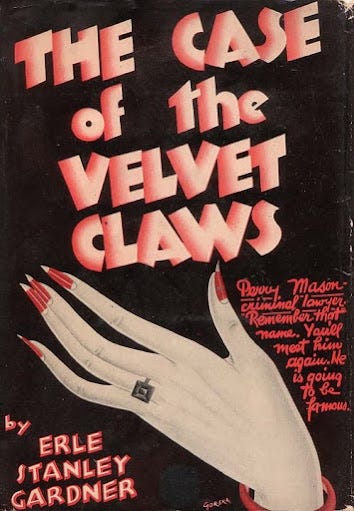

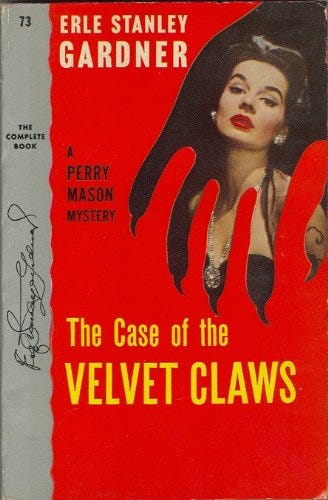

It also presented a vision of Perry Mason that was entirely new to me. Though I was familiar with how many represented Raymond Burr's version of Mason, I had never watched an episode of the original 1957 series in which he starred (this has changed recently). I had also never read a single volume of Erle Stanley Gardner's long running series that began in 1933 with the publication of The Case of the Velvet Claws. My understanding of the character was that he was morally forthright and facilitated cross-examination confessions from the actual perpetrators of crime. In fact this image of the cross-examination confession had become so deeply engrained in society that it has become a trope of the legal procedural genre, the genre that Gardner helped to found.

Instead of the modern day elderly knight in shining armor, a kind of legal Obi Wan, the HBO series showed a character who was not yet an attorney and who was far more hard boiled than the character in the TV movies. In fact, hard boiled references abound in the show and especially alludes to the fiction of Dashiell Hammett. Mason's status as a veteran and work as a Private Investigator evokes Dashiell Hammett's real life biography and the use of the name Effie for Mason's mom in the HBO show evokes Hammett's classic novel The Maltese Falcon. Such connections are clearly intentional and they show a reverence and knowledge of Erle Stanley Gardner's original novels and an appreciation for the American detective fiction genre. The first season of Perry Mason presents an origin story for Perry Mason and it ends with a woman named "Eva Griffin" walking into Mason's office with an offer of employment. This moment is the opening scene of The Case of the Velvet Claws.

The Case of the Velvet Claws was published in 1933 and marks Perry Mason's introduction to the wider world. Though Erle Stanley Gardner had been writing for the pulps for years, it was the publication of The Case of the Velvet Claws that vaulted him into a long and successful career as one of the most widely sold authors of all time. Perry Mason stories also provided the fertile soil from which the genre of Courtroom Procedural grew. It wasn't the first Courtroom Procedural, Arthur Cheney Train's character Ephraim Tutt predates Mason by over a decade. In fact, The Case of the Velvet Claws doesn't even involve a trial and it presents a Mason far different from my elderly knight in shining armor assumptions.

What The Case of the Velvet Claws does is establish a core cast of characters and a plot formula that provides a solid foundation that is entertaining and easily adapted by other authors. In a way, Perry Mason and Crew are the Justice Society/Justice Inc. of mystery fiction. Where Sherlock Holmes introduced the "sidekick" to mystery fiction, The Case of the Velvet Claws added the "team" and the "legal system" to the genre. Yes, Holmes dealt with the police, but Mason and his team navigate mysteries from before the inciting incident through the full legal resolution.

We know that Erle Stanley Gardner became a successful writer and that Perry Mason has become one of the most popular and influential characters in mystery and suspense fiction, but how well does The Case of the Velvet Claws stand up as a work of fiction?

The "TL;DR" answer is that the book is fantastic and that you should pick it up immediately. The longer answer follows and includes comparisons to the Perry Mason of the HBO Show and the 1957 series (which I've also begun watching post-HBO series).

The Plot

The Case of the Velvet Claws opens with "Eva Griffin" coming to Perry Mason's office with an appeal that he represent her in a delicate matter. It so happens that the night before visiting Mason, Eva Griffin had been attending a private dinner at the Beechwood Inn and that there had been a hold up at the location. She had been attending the event with a politician who's name had been left out of the list of those interviewed at the robbery and that a scandal magazine called Spicy Bits has received information that this politician was there and that his name had been held back and will likely publish this information in their next issue.

Ms. Griffin has two main concerns. The first is that the politician's life will be ruined when it is discovered that he was having dinner with a mysterious woman and that police were willing to cover up this fact to protect him. The second is that her husband will find out that she's having an affair. She wants to protect the politician and herself and wants Perry Mason to work it out with the scandal rag that they take a payoff to not run the story. Mason agrees to take the case.

While the 1990s Perry Mason movies included stories that featured Spicy Bits style papers, the thought of Mason being used as a go between to stop the publication of a story didn't quite seem to match with my memories of how people presented the character. However, this story very much fits with the Mason of the 1957 series I’ve been watching over the past year and especially fits the Mason of the HBO show. One can see echoes of this basic plot in the Hammersmith Pictures storyline in the first episode of the new show. HBO's Mason understands the motivation of blackmail and how to deal with blackmailers because he's been one himself. The Mason of The Case of Velvet Claws has probably never attempted blackmail himself, but he's used to dealing with the kinds of people who engage in blackmail.

The Pugilist

Contrary to my earlier assumption that Perry Mason was a morally forthright character who was squeaky clean and honest, the Perry Mason of the books is a hard boiled character. He is as morally ambiguous as any character Dashiell Hammett or any of the authors of Black Mask wrote to thrill readers. Rather than being presented only as a passive academic character, Mason is described as a ruthless and efficient fighter:

"He gave the impression of being a thinker and a fighter, a man who could work with infinite patience to jockey an adversary into just the right position, and then finish him with one blow."

Gardner, Erle Stanley. The Case of the Velvet Claws (Perry Mason Series Book 1) (p. 8-9). Della Street Press. Kindle Edition.

Gardner refers to Mason as a fighter more several times in the novel and has Mason refer to himself that way as well, but Mason's fighting spirit is more than just in words and descriptions. It's also made manifest in his actions. His actions in defense of his client, in defense of himself, and when punching reporters for Spicy Bits in the face:

“Don’t get hard,” he said, “because it won’t buy you anything.” “The hell it won’t,” said Perry Mason. He measured the distance, and slammed a straight left full into the grinning mouth. Crandall’s head shot back. He staggered for two steps, then went down like a sack of meal.

Gardner, Erle Stanley. The Case of the Velvet Claws (Perry Mason Series Book 1) (p. 42). Della Street Press. Kindle Edition.

Let’s just say that a Perry Mason who slugs someone so hard that they go down like a sack of meal is vastly different from my expectations. The Perry Mason of The Velvet Claws is a man of intelligence, to be sure, but he is a man of action and so is the private eye he most frequently hires, Paul Drake. Not only is Mason a man of action, he’s also shady as hell. I won’t get into particulars, because I don’t want to spoil the story, but the Perry Mason of the books pushes legal boundaries as far as they can go without breaking the law…and I’m pretty sure he breaks the law a couple of times.

The early episodes of the 1957 series don’t have Mason get physical, though the younger Raymond Burr in the show looks like a linebacker and they certainly could have, but they do have him act shady from time to time. Not shady enough to justify the continued skepticism of the police, but shady nonetheless. Literary Mason though? Oh yea, I get why the police don’t trust him. He’ll have a client “go on a trip” as quick as shit to prevent them from testifying. He’ll alter a crime scene to make a point about a witness and he’ll go even further.

The only thing that justifies Mason’s actions is the fact that universally, in The Velvet Claws and every other Mason novel, the client is not guilty of the crime they are accused of. Read that sentence again. Not guilty of the crime they are accused of. They might be guilty of something else, but it’s not the crime for which Mason is defending them. They also have often had their rights violated by the police. While the police in the Mason novels aren’t as incompetent as the police in the 1957 show, OMG is Tragg bad at his job, but they are just as willing to bend the rules as Mason. That’s why Mason is willing to bend the law in defense of his clients.

Mason tells his clients continually not to lie to him, to be honest so he can give them the best defense. Like Dr. House though, he knows they are all liars…even the innocent. When the truth can set them free, they still often choose to lie and Mason has to find out why and in finding out why he typically finds the way to win.

The Prognosis

The Velvet Claws is one helluva good novel and the closing scene of the book is the opening scene for the second. Gardner writes the first few books as if they are a serial. You get the mystery solved by the end of the book, but the book ends at the edge of a cliff with a new problem. We don’t often know what the problem is, but we know it’s lurking right out side Perry’s office waiting for Della Street to invite them in.