How Not to Design a Street Fighter Role Playing Game

Strange Licensed Role Playing Games Selection #7

Strange Licensed Role Playing Games and Me

As this is the seventh in an ongoing series of “strange” licensed role playing games, it should be pretty clear to all of you that I own a lot of role playing games and have very broad interests in terms of genre. The most common factor that will be mentioned in this series is that the game didn’t take into consideration a connection between the existing role playing game audience and the likelihood of buying a game based on a particular intellectual property. In other words, are there enough people interested in the idea in your existing pool of fans to take the risk of publishing a game on that idea?

I’ll be going into the underlying logic of this decision a little bit more below, but I found that this logic applies not only to publishing games but to my Newsletter posts as well. There are certain topics that do very well at Geekerati. Film and Television reviews (Luke’s and mine), role playing game discussions, and the Weekly Geekly Rundowns, not only have interest among current subscribers, they often bring in new subscribers. Then there are certain topics that do less well and last week had one of these posts. I did a book review of a Police Procedural written by Ed McBain that received about 70% of the normal readership and the interaction on the Note I shared about the post was among the least interacted with Notes I’ve written.

The message to me was clear, that I should take the post as an example of what those of us with MBAs call A/B testing and realize that this particular kind of article doesn’t vibe with readers as much as normal. After all, I cannot assume that all of you are as obsessed with the entirety of pop-culture as I am. I love everything from Flash Gordon to Midsomer Murders and from The Bachelor to La Bohème. As a writer, this is great as I always have something I can write about, but for you readers it sometimes means that there is something less interesting that shows up in your mailbox. I apologize for those moments and I will strive to keep things interesting.

I thought Ed McBain might fit a little bit more with the vibe here because McBain, under his birthname Salvatore Albert Lombino wrote a number of Science Fiction stories in leading pulp science fiction magazines. He eventually moved into crime and mystery full time, but he made some interesting contributions there. The post might have performed better if I’d given it a better headline that stressed the science fiction connection, or the Akira Kurosawa film connection, but that would require another A/B test.

The post and Note might also have been algorithmically suppressed the story is on a topic that might flag certain censorial actions, but given that the email open rate was low I think it was either the topic itself or my lack of connecting the topic to the things most of you like to read about. After all, there is a reason there aren’t a lot of successful police procedural role playing games. If pulp themed role playing games are the “fetch” of the hobby, police procedurals aren’t even that cool. There are reasons beyond the mechanics that Task Force Games’ Crime Fighter didn’t succeed back in the day or that the excellent French RPG C.O.P.S. wasn’t translated into English.

All of which is to say that while I think these might be “strange” choices for companies to make from a profit or interest based perspective, I totally understand it from a “I geek out about it” perspective. I’m probably not going to stop writing about things that might not fit with the typical post here, but I will work harder to connect any such posts to the themes that connect most with all of you.

The Logic of Licensing Games

Last week was GENCON, one of the largest and longest running gaming conventions in America and a number of readers are likely still in post-convention recovery mode. This means that today is probably not the best time to be publishing an article about a role playing game, but that’s just how I roll here at Geekerati. I aim to maximize topicality and timeliness. Speaking of which, that might also explain the lower numbers on the McBain article. Yeah, that’s it. It wasn’t that it was out of touch with most of my readers, it’s that my readers where busy. Just kidding.

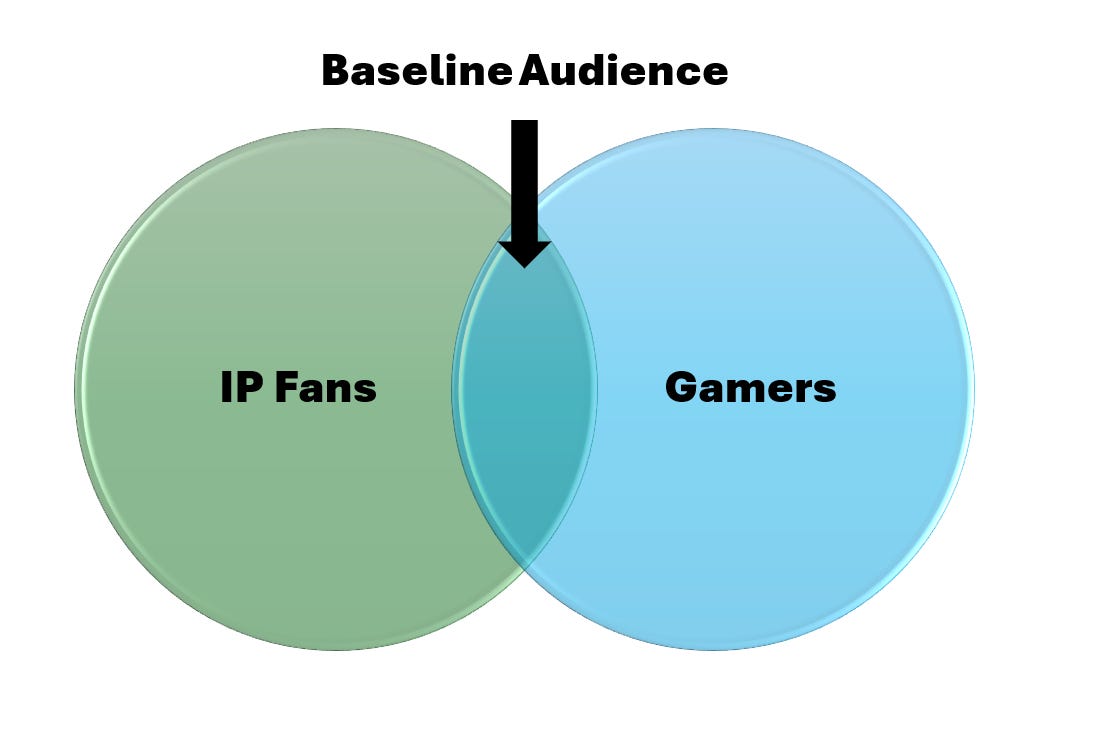

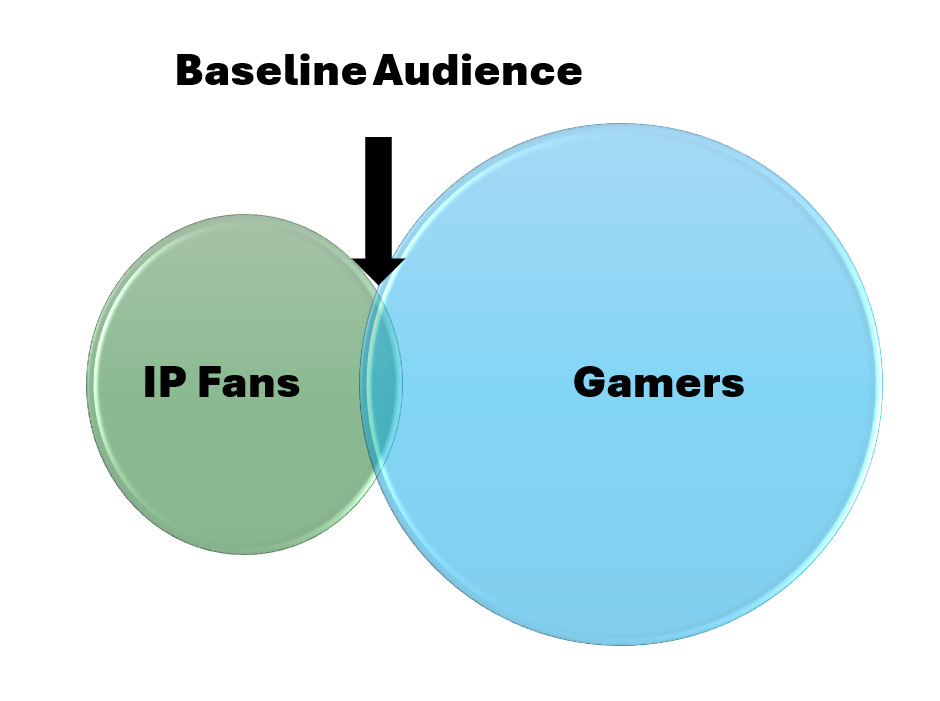

This past month, I started writing a series of articles about “Strange Licensed Role Playing Games” where I use each article to highlight a game that was “strange” for one reason or another. Sometimes that reason is that the way the game was initially published and marketed was odd (Pokemon Jr.), but most of the time it was because the game failed to balance the needs of the fans of the intellectual property with the desires of gamers who might also be fans of that property. It’s the overlap of existing fan and existing gamer that creates your baseline assumption for your customer base.

The bigger the overlap between the existing gaming community and fans of the IP or theme, the bigger your baseline audience. There are essentially three basic models this combination can follow: that the IP pool and gamer pool are of similar sizes, that the IP pool is larger than the pool of existing gamers, or that the pool of gamers is larger than the existing pool if IP fans. It can make sense to design a role playing game in any of these models, but how you approach the issue will vary.

If the total number of fans of a particular property and the total number of gamers are similar in size, then the size of your baseline audience is as big as the area where they overlap. Let’s imagine that the Highlander movie (there is only one) and the role playing game hobby are of similar total sizes, but that only some percentage of each group likes the other activity. In that case, your sales are going to be limited, of fairly decent size and it probably makes sense to run with the idea, so long as the mechanics and feel of the game match the expectations of the genre fans and the genre fits the preferred mechanics of enough of the gaming community.

Take Dragonlance as an example. Here the Venn Diagram is essentially a circle, and where it isn’t those outside the circle can be won over to into the overlapping area. If a person reads/listens to a Dragonlance novel and loves it, it is only natural to recommend they check out Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 1st Edition because it best captures the world of those books because those books have 1st edition mechanics as narrative elements. The inverse is also true. Those who like 1st edition AD&D are easier to win over because Dragonlance stories feel like D&D stories.

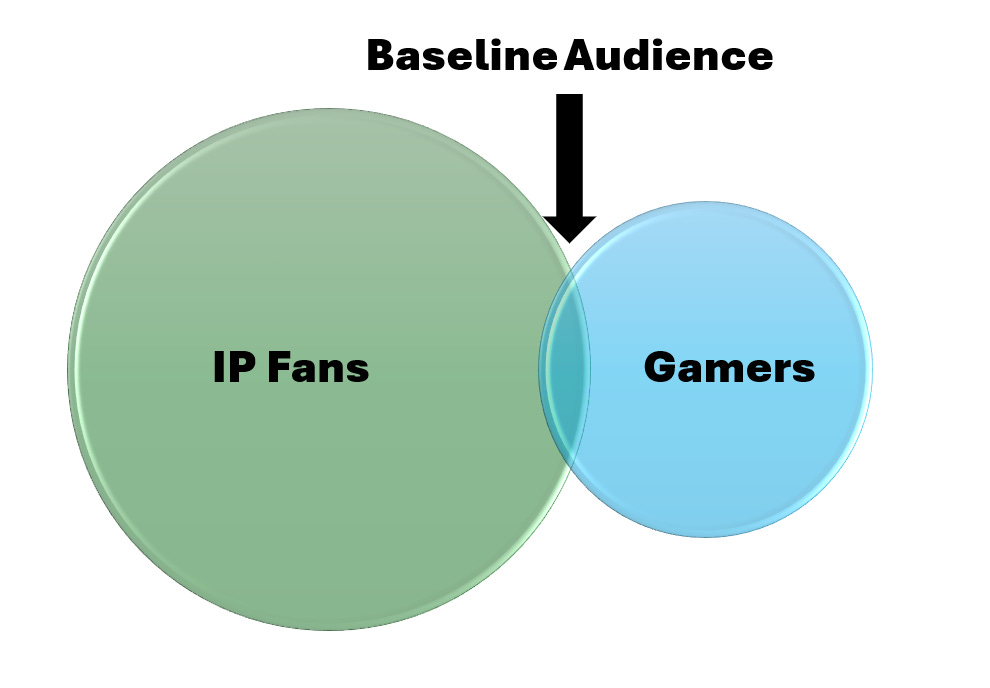

When the fans of the pop culture intellectual property significantly outnumber the number of gamers, it can still make sense to publish a licensed product, but you have to decide which route to take from a design perspective. Do you want to convince fans of your game mechanics to become fans of the setting and stories of the IP or do you want to convince fans of the IP to become gamers. The first strategy can expand a small initial baseline audience and can grow the audience of the IP as well. What isn’t visually displayed in these Venn Diagrams is the fact that after any initial overlap any growth in the baseline audience due to merger actually increases one or the other populations to a maximum of their combined population. Let’s it’s the late 80s/early 90s and you’ve got the opportunity to license Star Wars with its massive fan base. That fanbase significantly outnumbers yours, but if there is significant overlap or growth due to merger, then it makes sense for the IP holder to make a licensing deal.

When the Star Wars role playing game was released it was one of the major ways that Star Wars stories were still being told. Not only is it likely that some number of people became Star Wars fans because of the game, we know that the game shaped the in universe history of the Star Wars universe. It made sense for Lucas to make the deal with West End Games, but it made even more sense for West End Games so long as their rules set and “fluff” was accessible to non-gamers. West End used the mechanics Sandy Petersen, Lynn Willis, and Greg Stafford designed for Ghostbusters as the foundation for their Star Wars game and it worked like a charm. It was easy enough to learn for novice gamers, narrative focused enough for emerging story gamers, and crunchy enough for tactical gamers. It was exactly the right mix. In this case, it was the gaming company using the popularity of the brand to grow their audience and they made sure the mechanics and approach made sense.

When the population of active gamers is larger than the fan base of a pop culture brand, it’s pretty easy to convince the owners of the brand to license their property but it might not make sense for the gaming company. You are always taking a risk when you license a game and when you license a more obscure game the payoff is limited.

I’m pretty sure the fanbase for Steven Boyett’s The Architect of Sleep is pretty much me and thirty other people, so I imagine that Boyett would be pretty happy if someone came up to him offering him a way to make additional residuals on his fantasy novel. It might not make sense for a gaming company though. I don’t know how many gamers are looking to play a role playing game in a semi-grimdark setting populated with anthropomorphic Raccoons. I mean, I’m all in, but you’d have to win over a lot of skeptical gamers and you could probably create your own grimdark setting with anthropomorphic Raccoons that’s unique enough without needing to license the book.

Why the Street Fighter Storytelling Game was “Strange.”

Making a role playing game based on the highly successful Street Fighter franchise seems like a no-brainer. Right? You’ve got compelling characters in a world that is filled with espionage and kung fu battles. Port that combination into a smooth and cinematic game system like Feng Shui or Savage Worlds, or into a highly tactical system like Hero or GURPS, and you’ve got pure win. That’s not what happened here. In this case, the license was secured by White Wolf Publishing. You may know them as the company that:

Brought thousands of emos and goths into the gaming hobby with Vampire the Masquerade and other World of Darkness role playing games.

Fueled a revival of the classic game “rock, paper, and scissors” in the emo/goth community, because that’s how vampires get things done in live action Vampire games like Laws of the Night.

Had a game so popular it had a television series and a video game, based on it. Not to mention a certain film franchise or two that…Under(cough, cough)…that clearly has NOTHING to do with White Wolf’s World of Darkness. Wink, wink.

That list demonstrates one thing very clearly. White Wolf Publishing is masterful at creating games that depict a horrific gothic milieu in which young gamers can immerse themselves. White Wolf was into vampires and self-loathing before they were cool. They introduced a generation of gamers to Joy Division and a generation of Joy Division fans to gaming. I would argue that they were a part of the movement that helped to make those things cool. The storyteller system designed by White Wolf fosters wonderful role-playing experiences.

Each game within the overarching system has a core statistic that covers the internal struggle that various monsters face. Depending on the game, player characters have to grapple with personal stakes (Humanity, Rage, Banality) as they engage with a grim world. Each of these statistics make objective and mechanical the internal horror that each supernatural being faces. This helps players to experience a bit of the anxiety their characters face by giving consequences to their actions. White Wolf games, as the system’s name might give a clue, focus more on story than action. The inclusion of traits like Humanity and Banality magnify that the stakes are personal and internal.

What the heck does that have to do with bashing in the skulls of Zangief and M. Bison? At the time White Wolf released the Street Fighter game there was a tonal disconnect between the system and the licensed IP. That disconnect would be less if they released the game today. White Wolf has since released games like Exalted, Scion, and Aberrant. The fact that the last two games are now published by Onyx Path, and not White Wolf, shows that disconnect is still there. The storyteller system just doesn’t feel right as the basis for a “fight game.” It would have been a masterpiece as a Feng Shui expansion, but it fizzled as a White Wolf one.

What are some ways that the Storyteller System and the Street Fighter property don’t properly mesh?

The first is in the root mechanics of the game. The Storyteller System is a dice pool system where players roll a number of dice based on a combination of Attributes (innate talent) and Abilities (learned skills). You add your rank in an Attribute to your rank in the appropriate Ability and roll that many ten-sided dice. You then compare those dice to a difficulty number (from 2 to 10) and count the number of dice with that number or higher. This is the number of successes you achieve and it takes three successes to score a “complete success” anything less is a “partial success.” See that feels quick and easy just like the video game right? We haven’t even gotten to the combat system which expands on this basic system in order to add all of the cool special maneuvers Street Fighter is known for.

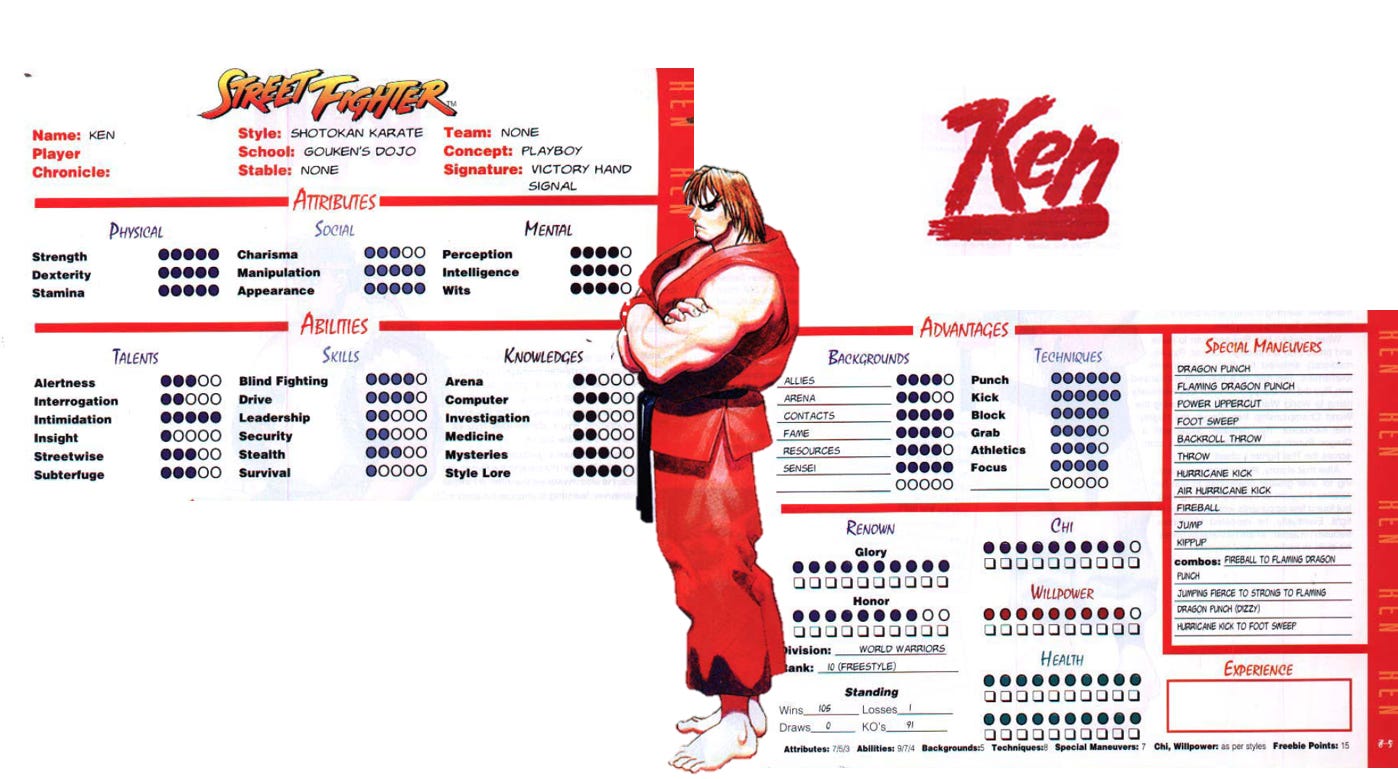

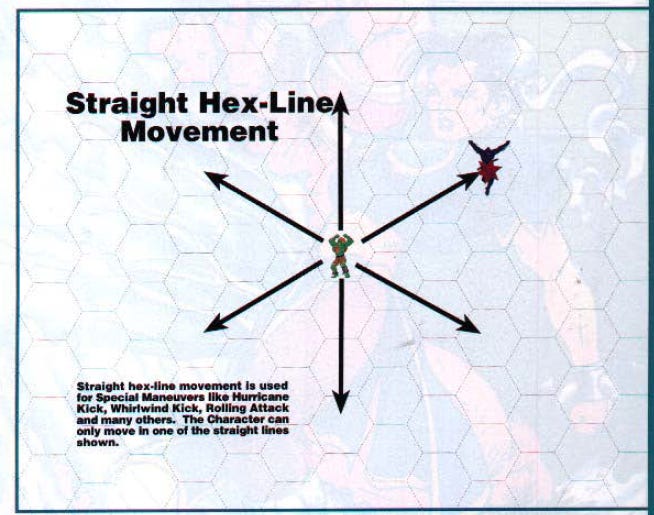

Let’s take a quick look at one of the core Street Fighters, Ken, too see how this looks on a sheet. For a gamer, especially one familiar with Storyteller System games, this is a fairly clean sheet, but for a non-gamer it can be intimidating. Add to that that how special maneuvers work isn’t explained and the intimidation factor gets dialed to 11. These maneuvers cost either Chi or Willpower to use, depending on if they are mystical or not, and each has particular limitations or bonuses associated with them. The system gets very granular and while Storyteller System games don’t frequently recommend using a map/grid for play, Street Fighter pretty much requires one.

The second oddity for non-gamers is the use of the Renown and Chi/Willpower factors. Chi and Willpower are expendable resources that affect not only how often you can use certain abilities, but like the Humanity ability for Vampire they also measure a core psychological/spiritual reserve. This wouldn’t matter if the game was primarily a fighting game, but White Wolf expanded Street Fighter-verse into a full role playing game setting and these abilities matter for social interactions and more.

I know it sounds like I’m being hypercritical of this game and I kind of am, but that’s primarily because it’s a fantastic game that failed to connect with either of its audiences. The combat system was too complex for a lot of Storyteller fans, though it was eventually adapted to the broader Storyteller system in the Combat book after the release of Werewolf: The Apocalypse. The Werewolf game was more combat oriented than Vampire and it made sense to broaden the system using the Street Fighter mechanics. The combat system does a very good job of capturing the subtleties of Street Fighter combinations and action, but it turns a 30 second fight into a 30 minute die rolling session. That’s not exactly what fans of the game want.

The Street Fighter Storytelling Game was strange because it was a theme change for the company, it wasn’t a great mechanical fit for new gamers, and made combat very tactical for a core gaming group that wanted narrative stories over action. I think that Street Fighter would have sold better using the Feng Shui or GURPS system, but that’s an unprovable counterfactual. It’s a great game that deserved a bigger audience, but its strangeness hindered that.

Is there a Strange game you’d like me to cover as this series continues?

More about Les COPS s’il vous plait?

The next weird licensed rpg I would like to see is Dallas! 😅