Ed McBain's "The Mugger" is a Tale Worth Reading

A Review of Ed McBain's Second 87th Precinct Novel

When I first listened to Professor David Schmid’s series of lectures on The Secrets of Great Mystery and Suspense Fiction for the Great Courses series, I had only a vague idea of who Ed McBain was. I’d seen the name on books at the airport, but I had never read a novel or story by the author and so I had no idea how important a writer McBain was in the mystery genre. To be fair, Dr. Schmid introduced me to a lot of fiction in that series of lectures, but looking back I really think I should have been more familiar with Ed McBain long before I listened to that lecture series.

Ed McBain is one of the many pseudonyms used by the prolific author Evan Hunter. Hunter was born with the name Salvatore Albert Lombino before legally changing his name to Evan Hunter in 1952. I’m not one to judge name changes, since I took my wife’s last name in 2008. As the many mis-sent emails I receive can attest, there are a lot of Christian Johnson’s in the world, but there is only one Christian Lindke. Having a unique name has advantages and drawbacks and given that Salvatore Albert Lombino had previously published Science Fiction stories under his birthname, that could have presented difficulties if and when he desired to publish in more mainstream publications.

Lombino’s first published science fiction story (near as I can tell based on a search of the internet speculative fiction database) was “Reaching for the Moon” in the November 1951 issue of Science Fiction Quarterly. Wikipedia credits “Welcome Martians” from the May 1952 issue of IF magazine as his first sale and even though that’s a year later, the vagaries of the publishing industry might mean that’s true. The 1951 issue of Science Fiction Quarterly includes a story by dynamic pulp duo C.L. Moore and Henry Kuttner (under their C.H. Liddell pseudonym), a short story by future SF/F publisher Lester del Rey, and an essay on a potential “esoteric meaning” to the Pyramids by L. Sprague de Camp. From a pulp fiction luminary perspective, that’s great company. From the perspective of an aspiring mainstream writer who sought “legitimacy” and wanted to sell a novel based on his 17 day stint as a teacher at Bronx Vocational High School, the science fiction past might be viewed as baggage.

Since Lombino (referred to as Hunter after this) had worked as an executive editor for the Scott Meredith Literary Agency since 1951, he understood the importance of name and brand and had already created the name Evan Hunter, which may be derived from Hunter college where he studied English Literature and Psychology, as a pen name for writing detective fiction. He legally changed his name to Evan Hunter in 1952 and that was the name he used when his novel The Blackboard Jungle was published in 1954. That novel was adapted into a film that examined “The Teenage Terror in the Schools!” Quite a claim from someone who spent SEVENTEEN DAYS as a teacher. That snark aside, the book and movie are quite excellent and Blackboard Jungle (the film drops the The) was nominated for four Academy Awards and is an inductee to the National Film Registry.

Blackboard Jungle was culturally important for its discussion of teacher expectations and teacher pay and it has also served as the thematic inspiration for films across the spectrum of film genres. You can see echoes of it in dramatic films like To Sir, with Love (which is a kind of high concept mashup of Blackboard Jungle with Goodbye, Mr. Chips) and Teachers, as well as in Teachsploitation films like Only the Strong and The Substitute.

When Hunter decided to write police procedural novels, he created the Ed McBain pseudonym for that purpose. Under the Ed McBain name, Hunter wrote over 50 novels telling the story of the detectives and foot patrol officers of a fictional police precinct. In the introduction to the second volume, The Mugger, he claimed that the reason he chose to write a police procedural is that he wanted narratively answer the question of what it would be like if a police precinct was the protagonist, rather than a single character.

While Hunter had written a number of private eye detective stories in magazines like Manhunt, one of the great crime magazines of the mid-20th century, Hunter (as McBain) has often been quoted as saying, as he was in this 2005 Slate Magazine story, that “the last time a private eye solve a murder was never.”

“The last time a private eye solved a murder was never.” — Ed McBain

It’s a great quote, but I’ve never found an interview with that exact statement. I’ve found lots of articles quoting past articles with the quote, but never a primary source. This initially led me to believe that it was apocryphal but now I believe it to merely be a slight misquote based on memory. It looks like one of those cases where a person remembers reading something and restates it, but where the paraphrase is slightly off. There is a similar quote in Long Time No See, the 32nd novel in the 87th Precinct series, where Detective Steve Carella says something very similar.

He did not subscribe to the theory that all homicides were rooted in the distant past; he would leave such speculation to California mystery writers who seemed to believe that murder was something brewed in a pot for half a century, coming to a boil only when a private detective needed a job. The last time Carella had met a private detective investigating a homicide was never. — Steve Carella in Long Time No See, 87th Precinct Series #32 by Ed McBain

As with The Blackboard Jungle, the 87th Precinct novels have been extremely influential. Not only have there been a television series and TV movies based on the project, but there have been major films as well. The television influence has ranged from police dramas like Starsky and Hutch, Hill Street Blues, and NYPD Blue, to comedies like Brooklyn 99. There were even two Columbo movie episodes based on 87th Precinct stories, but given the tonal differences between the properties they are among the weakest Columbo entries. The Columbo-verse is about the everyman bringing down arrogant elites and the 87th Precinct is about multiple storylines overlapping with the private lives of police officers. Both are great, but they are very different.

Even an Akira Kurosawa film. High and Low (which is being remade by Spike Lee this year) was based on an 87th Precinct novel titled King’s Ransom. Given that Hunter was a screenwriter, he wrote the screenplay for The Birds for Alfred Hitchcock, it isn’t surprising his work might get adapted to visual media, but it is remarkable how wide ranging his influence is.

Which brings me to my review of the 2nd novel in the 87th Precinct series, The Mugger. Where the first novel, Cop Hater, drew heavily on film noir tropes from films like Double Indemnity, The Mugger draws more on Hunter’s own experience as a school teacher, the same experience that inspired him to write The Blackboard Jungle.

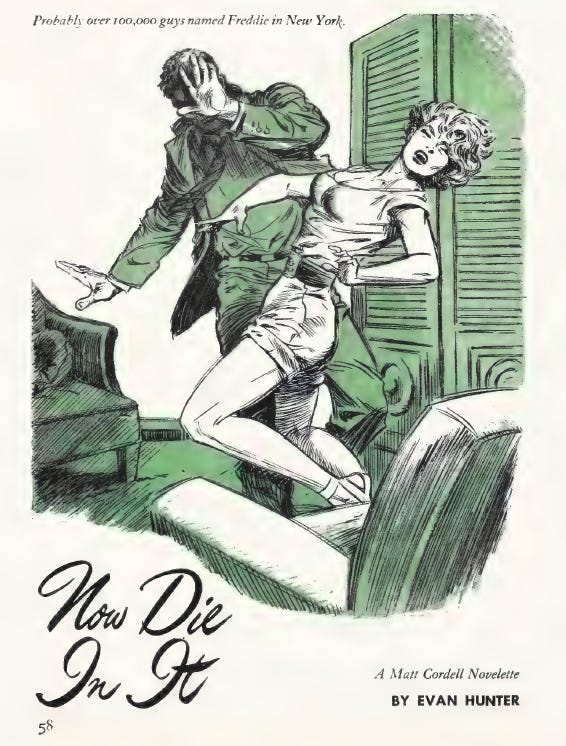

The Mugger is based on Evan Hunter’s novelette “Now Die in It!” published in the May, 1953 issue of Manhunt Magazine. “Now Die in It!” was an entry in Hunter’s “Matt Cordell” series of detective tales, but as McBain he reworked the story to fit within the narrative dynamics of a Police Precinct. This meant the addition of an additional plot line (the book has an A and B storyline and most 87th Precinct novels have multiple arcs) as well as the changing of a number of minor details.

Where Matt Cordell was a private eye investigating a murder in the short story, take that Steve Carella, the investigator here is a beat cop by the name of Bert Kling who aspires to be a detective some day. Kling has been asked by an old high school acquaintance to talk with that acquaintances sister-in-law because she might be seeing a bad crowd. Shortly after Kling talks to the woman, she is murdered.

This murder happens in the context of two other mysterious crime waves occurring in The City. There’s a person stealing and murdering people’s cats in the 33rd Precinct and there is a serial mugger victimizing the citizens in the 87th Precinct. When sunglasses similar to those worn by the mugger are found at the murder scene, the police suspect that the mugger and the murderer are likely to be the same person.

The novel directly follows Kling as he investigates the murder on his free time and the mugger investigation by the detectives of the 87th Precinct. The investigation of the cat killings is covered in the background of the story as is the footwork of the Homicide division who are also investigating the murder. By having readers experience some narratives first hand, while leaving others to the background, McBain makes the world feel real. The books are short (around 200 - 250 pages), but the world feels deep. When Kling finally has a clash with the Homicide division, because he is stepping into their territory and might be screwing up there investigation, the world gets even more realistic as interdepartmental politics come to the fore.

One of the things I love so far about the 87th Precinct books, I’m only two in so this might change, is how many false leads the police follow in the mysteries. It gives the stories a nice sense of realism as you are watching them actually solve a crime in a way that discourages trying to outsmart the detectives. In the first novel, Cop Hater, the killer and motive were obvious, but you kept reading because the story was about the police figuring it out. These aren’t genius detectives, these are hard working people doing there best.

Though the story is an adaptation of Hunter’s previously written tale, “Now Die in It,” the added narrative lines change the story significantly. But McBain did more that change just the narrative arcs, he changed the entire worldview of the main character. Matt Cordell, Evan Hunter’s Private Eye, is a hardboiled figure who sees the world from a pessimistic view point. When he thinks about “Freddie,” the murderer, he sees a world around him that is dying and filled with naive individuals who are seduced by Spring even though Winter (and death) is Coming.

Freddie.

Just a name. Juse one Freddie out of the thousands of Freddies in the city, the millions of Freddies in the world. Gather them all together, shuffle them, cut, and then pick a Freddie, any Freddie.

It was not a day for picking Freddies.

There was a mild breeze on the air, and it searched my face and the open throat of my shirt. The streets were crowded with people seduced by Spring. They breathed deeply of her fragrance, flirted back at her, treated her like the mistress she was, the wanton who would grow old with Summer’s heat and die with Autumn’s first chill blast. The man with his hot dog cart stood in the gutter, and the sun-seekers crowded the sauerkraut pot, thronged the umbrella-topped stand. The high school girls ambled home with all the time in the world, with all their lives ahead of them, senior hats perched jauntily on their heads, young breasts thrusting at loose sweaters. The men stood around the candy stores, or the delicatessens, and they talked about the fights, or the coming baseball season, and they looked at silk-stockinged legs and wished for a stronger breeze.

Or they went about their jobs, delivering mail, washing windows, fixing cars, and they drew in deeply of the warm air and sighed a little. It was Spring for them, at last.

And one of them was Freddie.

And Freddie was just a name.

I walked along Burke Avenue, wondering how long it had been since I’d eaten a hot dog, since I’d seen a baseball game, since I’d cared. A long time. A long, long time. And how long ago to seventeen? How many years, how many centuries?

What does a seventeen year kid think like?

Matt Cordell is a person who is so jaded that he has forgotten what seventeen is like, a fact that hinders his investigation for a time. Bert Kling is a very different figure and much easier to sympathize with and root for. You want him to win, not just in his investigation but in his personal life as well. Here is the adapted version of the passage from “Now Die in It” as it is presented in The Mugger.

At 10:00 that night, Kling stepped off an express train onto the Peterson Avenue station platform of the Elevated Transit System. He stood for a moment looking out over the lights of the city, warm and alive with color against the tingling autumn air. Autumn did not want to die this year. Autumn refused to be lowered into the grave of winter. She clung tenaciously (Tenacious, anyone? he thought, and he grinned all over again) to the trailing robes of summer. She was glad to be alive, and humanity caught some of her zest for living, mirrored it on the faces of the people in the streets.

One of the people in the streets was a man named Clifford.

Somewhere among people who rushed along grinning, there was a man with a scowl on his face.

Somewhere among the thousands who sat in movie houses, there might be a murderer watching the screen.

Somewhere where lovers walked and talked, he might be sitting alone on a bench, brooding.

Somewhere where open, smiling faces dispelled plumed, brittle vapor on to the snappish air, a man walked with his mouth closed and his teeth clenched.

Clifford.

How many Cliffords were there in a city of this size? How many Cliffords in the telephone directory? How many unlisted Cliffords?

Shuffle the deck of Cliffords, cut, and then pick a Clifford, any Clifford.

This was not a time for picking Cliffords.

This was a time for walks in the country, with the air spanking your cheeks, and the leaves crisp and crunching underfoot, and the trees screaming in a riot of splendid color. This was a time for brier pipes and tweed overcoats and juicy red McIntosh apples. This was a time to contemplate pumpkin pie and good books and thick rugs and windows shut tight against the coming cold.

This was not a time for Clifford, and this was not a time for murder.

But murder had been done, and the Homicide cops were cold-eyed men who had never been seventeen.

Kling had once been seventeen.

Note that the season has changed. In the short story it was Spring and the world was filled with naive residents who didn’t know death was coming for them. In The Mugger, it’s fall and the world is beginning to die as it does every year, yet Kling is optimistic and the world is fighting to live. It is the world view of an optimist, of a man who is in love and Bert Kling is falling in love. The evil that is out there is still a threat, but Kling is going to stop him because Kling had once been seventeen and he remembers what joy feels like. The sentiments of Matt Cordell are shifted onto the Homicide cops, men whose hardness we have yet to see directly at this point in the novel, but when we do meet them we see why it is Bert and not them who are seeing the real motive behind the murder. The way Kling’s compassion and optimism is revealed is poetic.

The dichotomy of dread and hope, fear and joy, desperation and humor are sprinkled throughout the novel and they make it a quick read. As with Cop Killer, the mystery is no great puzzle. You may or may not solve it before Kling, but when the killer and motive are revealed it makes perfect sense. There are plenty of false leads, but McBain doesn’t cheat in his solution. It’s a murder motive that feels real, because you’ve read things like that before in the newspapers. Underlying all the tension in this case is an examination of what the transition from kid to adult might look like for some of those kids in The Blackboard Jungle.

4/5 Stars.

Hunter/McBain was an interesting storyteller at any word length.