Wait! What?! Lin Carter Wrote a Flash Gordon Role Playing Game?

Strange Licensed Role Playing Games Selection #8

When a Good Licensing Idea Goes Bad

Fantasy Games Unlimited was one of the most popular small publishers in the early days of the role playing game hobby. They produced a number of classic, if now obscure, role playing games that included games of pulp influenced heroic action (Daredevils), swashbuckling daring do (Flashing Blades), Cronenbergian dystopian science fiction horror (Psi World), cutting edge Fantasy/Sword & Sorcery (Swordbearer), post-apocalyptic adventures (Aftermath!), the Watership Down influenced Bunnies and Burrows, and one of the best superhero role playing games ever produced (Villains & Vigilantes this links a module for reasons that will soon become clear).

Like many small and mid-sized companies in the early role playing game scene they were not always the best run business, monetarily or ethically. This lack of solid business sense led the original creators of Villains & Vigilantes to sue Fantasy Games Unlimited to secure ownership of the Villains & Vigilantes game. That’s a story for another time because the underlying legal conflicts, and the morals underpinning them, are complex.

Each of the games Fantasy Games Unlimited produced had a bespoke game system, a sadly dying trend in the industry, and they were very much on the cutting edge of the role playing game industry by the mid-1980s. But every company has to start somewhere and when Scott Bizar launched Fantasy Games Unlimited one of his first products was a rarely discussed licensed wargame called Royal Armies of the Hyborian Age. The rules were written by Lin Carter (editor of the Ace Conan series of novels) and is still available in pdf from FGU today. Lin Carter was Bizar’s roommate at the time he wrote the book and while I have no idea what the particulars of the licensing deal were at the time, I’m going to guess that they were pretty generous. After all, when your roommate is partially in control of the license, it follows that the terms might be in your favor.

Royal Armies of the Hyborian Age was not the first set of rules to use Robert E Howard’s setting. British wargaming enthusiast Tony Bath, whose own medieval miniature rules would go on to influence Gary Gygax and others, ran a miniatures based wargame campaign for his friends that took place in a variation of Conan’s Hyboria as far back as 1957. I’ve written about the influence of Tony Bath’s campaign on the hobby in the past, but as influential as his Hyboria setting was it was never made commercially available. Lin Carter’s 1975 wargaming rule are the first commercial game to take place in Conan’s world, but TSR would soon follow in 1976 when their Gods, Demigods, and Heroes supplement would include rules for Hyborian heroes and gods. I’ll discuss those rules in a later column, but I will note that reprints of the book lack that chapter because Hasbro lacks the Conan license. Something to consider when wondering what the status of Fantasy Games Unlimited’s license is.

Royal Armies of the Hyborian Age wasn’t the only game product that Lin Carter wrote for Fantasy Games Unlimited. He also wrote a role playing game that is strange primarily for the fact that the author didn’t quite understand everything that players wanted in a role playing game at the time. That second game that Lin Carter wrote was Flash Gordon & The Warriors of Mongo and it is one of my favorite strange licensed role playing games.

Flash Gordon & the Warriors of Mongo was published in 1977 by Fantasy Games Unlimited and it is one of the earliest Science Fiction/Science Fantasy role playing games to ever come to market. The first two games in this genre were TSR’s Metamorphosis Alpha (1976) and Ken St. Andre’s Starfaring (1976), both of which are based on original setting concepts that are very reflective of the vibe of the mid-1970s. The first combined the space arc and post apocalyptic genres while the second was very much gonzo 70s sexploitation SF that combined Playboy style cartoons with a John Carpenter’s early film Dark Star. Flash Gordon was very different from those games in that it was aimed at an existing fanbase outside of the role playing market.

In addition to being one of the first SF role-playing games, Flash Gordon was also one of the first fully licensed role-playing games. In his classic Heroic Worlds, Lawrence Schick claims that the Dallas Role Playing Game was the first officially licensed game (on page 423, if you are wondering). This is a rare case where his invaluable resource is incorrect. Flash Gordon predates Dallas by three years and lists the following under its copyright notice, “This rule booklet is published under license agreement with King Features Syndicate.” I don’t know if Flash Gordon was the first licensed game, but in was one of the first.

The Flash Gordon role playing game was an attempt to create an entirely self contained role playing game complete with campaign setting and campaign in a single 48 page volume. That's quite a daunting thing to attempt and I have been surprised at how well Flash Gordon accomplishes its goal, especially given the low esteem in which the RPG.net review holds the game. Given that I’ve actually read and run the game, I am quite stunned at how many reviewers still paraphrase the assertion made in the one comment on RPG.net that, “This is actually far more of a chase game than an RPG and suffers from the plot being fairly one dimensional, after all to complete it you have to overthrow Ming the Merciless whatever the buildup play.” The comment is untrue and the repetition of it is yet another demonstration more of how often people rely on others for information rather than giving something a look themselves.

In my opinion, Flash Gordon and the Warriors of Mongo is a fully flushed out role playing game with a campaign system that pre-dates the later Savage Worlds Plot Point campaign innovation, but that presages it as well. The events of the game are plotted in zones where certain specific encounters occur, encounters that culminate in a campaign resolution based on the first couple of years of the Alex Raymond run of the Flash Gordon comic strip with the rebellion of the Power Men against Ming.

The book has its flaws, but it also has its brilliance. The flaws lie within the underlying rules in the conflict resolution system. The brilliance lies within the freeform campaign implementation system, which as I mentioned above is a system remarkably similar to the Plot Point and Encounter Generation system mastered by Pinnacle Entertainment Group in their Savage Worlds series of games. Unlike that Plot Point system, Warriors of Mongo is more like a branching railroad than the freeform tool Pinnacle invented, but more on this later. It's time to look at Flash Gordon & the Warriors of Mongo.

System Mechanics

In a brief note at the beginning of the book Lin Carter sets out his chief objective in the drafting of Flash Gordon. "My own personal debt to Alex Raymond, and my enduring fondness and admiration for Flash Gordon made this set of rules a labor of love. I was dead set against Scott's [Scott Bizar] first idea of doing a book of wargame rules and held out for adventure-scenarios, instead."

Carter wanted a game that was able to capture the excitement of the old Flash Gordon serial through the use of a collection of adventure-scenarios bound by a single rules set. Rules that were intended to "provide a simple and schematic system for recreating the adventures of Flash Gordon on the planet Mongo." With regard to their goals, Carter and Bizar both succeeded extremely well and failed monumentally.

The system is simple...and confusing...at the same time.

Characters roll three "average" dice for the following four statistics -- Physical Skill & Stamina, Combat Skill, Charisma/Attractiveness, and Scientific Aptitude. It's an interesting grouping of statistics that demonstrated FGU's willingness to look beyond the "obligatory 6" statistics created by TSR. The inclusion of Combat Skill as a rated statistic is in and of itself an interesting choice.

At no point is it explained what an "average" die is. Is an "average" die a typical six-sided die that you can find in almost every board game ever published, or is it one of those obscure and hard to find "averaging" dice mentioned in the Dungeon Master's Guide? The rules aren't clear regarding this, but the fact that "rolls of over 12 indicate an extremely high ability in the specific category" [emphasis mine] hints that it is the "averaging" die to which they are referring -- later difficulty numbers hint that it might be the regular dice that are used.

The new gamer would have only this clue, but wargamers of the era would know that an "average" die was a six-sided die with the numbers 2, 3, 3, 4, 4, 5 printed on it instead of 1 through 6. This die was used to reduce the influence of uncertainty on outcomes in wargames at the time. More recent games, like Warhammer, rely on regression to the mean and buckets of dice to reduce uncertainty. It may seem counter intuitive, but the more often you roll the less uncertainty influences outcomes because the likelihood that the total distribution of the rolls is normal increases.

Not that it matters much, as you will soon see.

After rolling statistics, players choose from one of the following roles -- Warrior, Leader, and the Scientist. This leads one to wonder which group Dale Arden fits, an oversite similar to that made in early John Carter role playing games as well, but that is another conversation entirely. Though I will state for the record that my vote is for Leader. The primary effect of choosing a particular roll is to add one point to the statistic most related to the profession.

These attributes are later used to determine success based on a very simple mechanic. Stat + d6 > TN. Let’s take a look at a possible conflict the players may encounter.

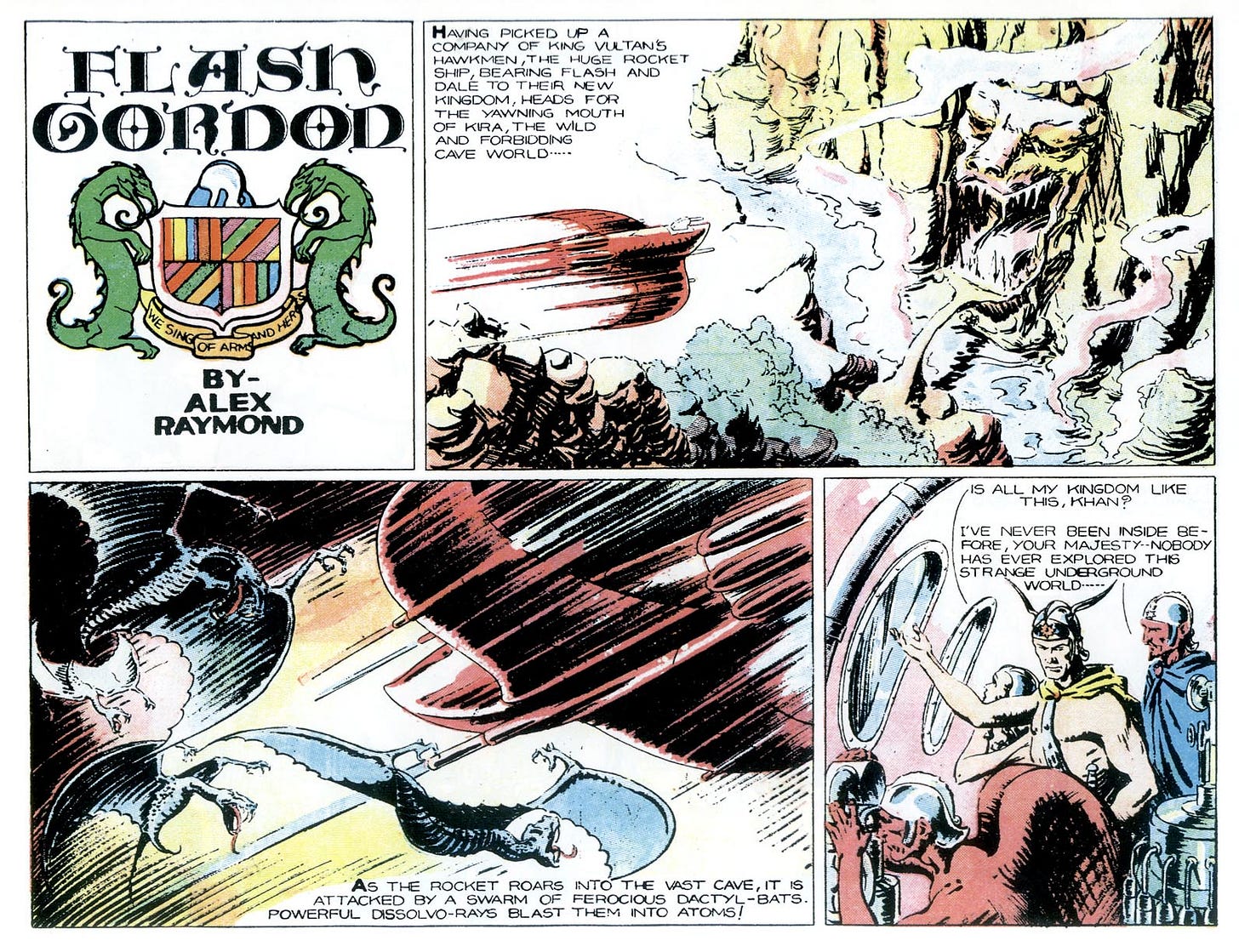

If the characters find themselves in the Domain of the Cliff Dwellers one possibility is that they will encounter the deadly Dactyl-Bats. Let’s say the players decide they want to fight off the Dactyl-Bats. The success or failure of this action will "depend upon the combat skill of the most skilled member of your group. Roll one die and add the result to your military skill. A final total of fourteen or greater is needed to drive off the Dactyl-Bats." Failure indicates the character is wounded and that the party must rest. It's a simple resolution, but one that lacks any significant cinematic quality.

This conflict resolution feels awkward and mildly unsatisfying. Other mechanical resolutions in the game are similarly weak. All conflicts are resolved strictly via single die rolls and the typical punishment for failure on an action is a loss of a certain number of turns. These turns are valuable as players need to recruit enough allies to defeat Ming before he has time to become powerful enough to squash any rebellion. While the statistics of the game are firmly rooted in roleplaying concepts, the resolution and consequence system still echoes board game resolutions and this is probably why many say the game plays more like a board game than a role playing game. This is one of the game’s key weaknesses, as is the inconsistency of resolution techniques. For example, fighting a Snow Dragon is resolved in a different manner than the encounter just discussed.

I imagine one could build a good game conflict resolution system built around the statistics highlighted in Flash Gordon, but this book lacks that system and there are no real rules for how to “role play.” Then again, there weren’t rules for that in most role playing games at the time either. What is intriguing here is the move away from tactical resolution to narrative resolution. Yes, it’s primitive and reviewers are right to critique it, but with only a slight tweak the system is essentially a parallel to Apocalypse World and/or InSpectres.

Rather than adapt the game’s current system, I’d probably just use this series of encounters as the basis for a Savage Worlds campaign. I also think it might be interesting to try to use a modified version of the Dragon Age pen and paper rpg system, the AGE system, as a substitute for the mechanics in the Flash Gordon rpg. There is something about the stunt system within those mechanics that I think really suits the pulp/cliffhanger genre. The AGE system is simple enough that it wouldn't require a lot of work to adapt it. One could also use the OctaNe system, itself a modification of InSpectres, if one wants to stick to the "narrative" feel that Bizar and Carter seem to have been attempting here. OctaNe succeeds where this game fails mechanically -- and OctaNe's system is ridiculously easy to learn and use.

Game Campaign System

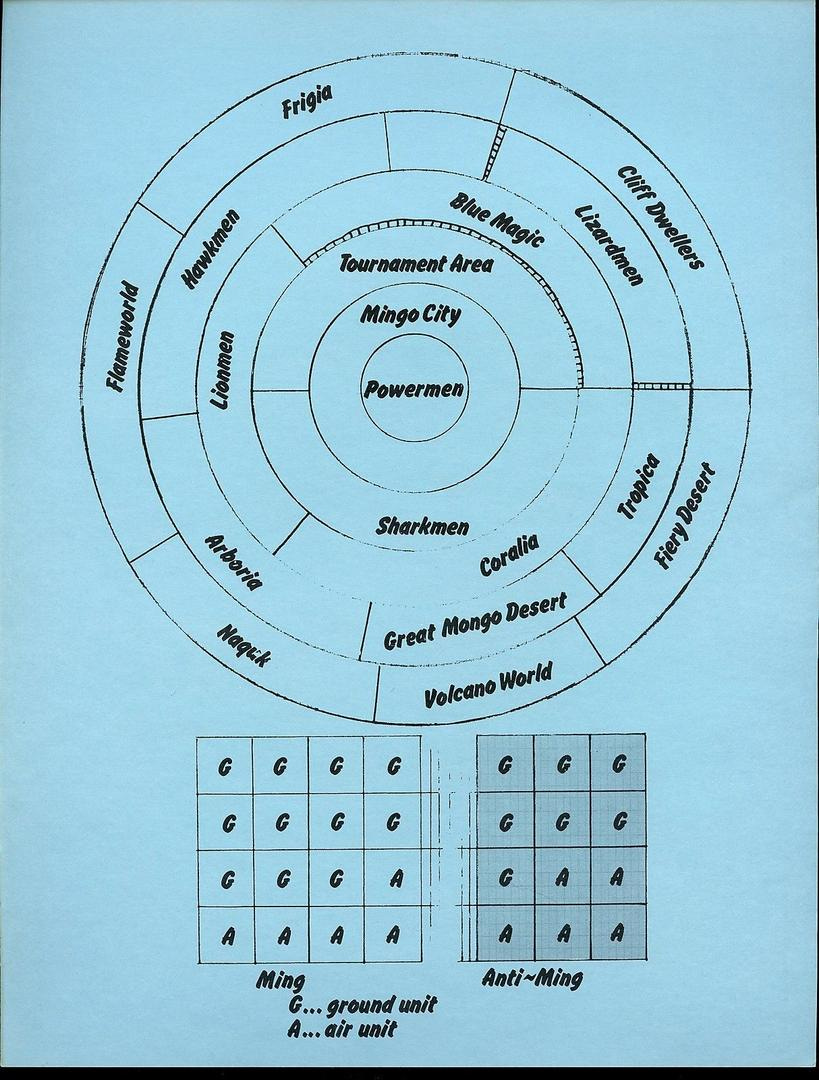

This is where Flash Gordon really shines. The game's basic structure is that of a "recruitment" campaign where the players must journey from land to land -- based on how they are connected on an abstract schematic and not based on actual geography though the schematic takes those into account -- where they encounter various challenges and face various foes. For example, let's say our stalwart heroes find themselves in the Fiery Desert of Mongo. If they are mounted on Gryphs he journey will be easier than if they are not. It is possible, though not guaranteed, that the players will encounter Gundar's Gandits who will attempt to capture the players and sell them into slavery. The players may also encounter a Tropican Desert Patrol made up of troops loyal to Ming. The end goal of the area is for the group to recruit Gundar and his men, but that requires role playing and/or defeating the Tropican Desert Patrol. The description of the Desert and the possible encounters are abstract enough that they could easily inspire several sessions of roleplaying -- with a robust system like Savage Worlds -- all it lacks is a nice random encounter generator like the one found in The Day After Ragnarok to fill in the holes.

In essence, the Flash Gordon role playing game includes one or more major encounters for each geographical region of Mongo. As they players wander from place to place, they can/will face these challenges. What is inspired, and ahead of its time, about this structure is that the encounters are "story plot points" that must be achieved but can be achieved in the order of the player's choosing. There is room for exploration of the world at the same time that the players are succeeding at mandatory plot points. It is a narrative campaign without the railroading. Pinnacle Entertainment Group uses a similar structure in their Rippers, Slipstream, and Necessary Evil campaigns. It is a system that allows for narratively meaningful and fun play without the need for extraordinary planning on the part of the Game Master. All it lacks is a method, like the random encounter generator I mentioned above that is used by most plot point campaign systems, to fill in the scenes between the set pieces. Though it should be noted that there is sufficient information within the Flash Gordon rpg to easily construct a set of encounter generators with very little work.

If it is so great, why is it “strange?”

As much as I love the campaign system and think that Flash Gordon is innovative in this regard, the criticisms regarding the underlying conflict mechanical system, or lack thereof, are spot on. Character generation and conflict resolution lack any feeling of consequence or depth and the game was released at a time when gamers were demanding more and more specificity in how characters were emulated mechanically. With each new Supplement, D&D became less abstract and in turn more playable as a game and players likely wanted other offerings to match that and the game was largely a failure.

This is too bad because if you want a campaign road map to use with another game system, my personal choice would be a fast-furious-and-fun one or a "narrativist" one, then this product is a deep resource. It will save you from having to read pages and pages of the old Alex Raymond strip in order to get an understanding of all of the minor details necessary for the creation of a campaign. You should certainly read the Alex Raymond strips, they are wonderful, but reading them should never be made to feel anything remotely like work. Bizar and Carter have done the work in presenting the campaign setting, all you have to do is adapt it to your favorite quick and dirty rpg mechanical set.

Sword & Planet tales are a perfect milieu for adventure gaming and Flash is one of the premier characters of the genre. It’s also strange to think that Lin Carter had a hand in writing the rules to a role-playing game, but that’s another conversation entirely and that isn’t what makes this game a strange licensed game. As I mentioned what makes Flash such a strange choice is the way the game rules are set up.

This game could have gone down as one of the best licensed games in the history of the hobby. The reason it didn’t is because the designers did not put the time and effort into creating a complete rules set that could be understood by gamers new and old. It’s not a mere one dimensional boardgame, but it is a game that takes a good deal of effort to run as is and it’s a better campaign supplement for your role playing game of choice. The game features all the strengths and weaknesses of the games released in the first few years of the gaming hobby. It is imaginative and inspires creativity, but it is vague and doesn’t quite convey what is being attempted.

Instead of “Flash! Ahhh!,” we get “Flash! Awww….” (Sorry. That had to be done.)

Thanks for writing this up. I've always been curious. I agree that the Flash Gordon world would be an amazing gaming experience, but it would require the GM to do some homework.

I Loved FGU's games, not because they were playable (Bob Charrette never met an overly-complicated mathematical sub-system he didn't like), but because they tried very hard to capture the spirit of the genre they were working towards. I think the only one that really nailed it was V&V (obviously!) but Daredevils had some interesting ideas in the character creation system, including a life path to simulate the knockabout characters who went from one thing to another until they became a bush pilot or whatever. There was a lot to learn from reading those FGU games. They were a big influence on my gaming "journey."

I own this game and your review is spot-on. I bought it years ago, hoping there was enough to adapt to a primarily narrativist game. Sadly, not. However, I have since discovered a 99 cents wonder - https://www.drivethrurpg.com/en/product/114358/flash-arghhhhh

This actually is a narrativist rules-light system. characters are defined by two attributes - Prone & Good which equate to flaw & talent. It gives you a few random tables, one for determining action outcomes and a scene based story structure that can be adapted to multiple adventures.

Now that I think about it, I could probably combine the two games. Hmm...