Wolf Man (2024) Review: Furry's a Jolly Bad Fellow

How does Brundle-wolf eat, anyway?

Lycanthropy, or werewolfism, as depicted in most modern cinema, is transmitted to its victim by a bite, like rabies, giving it all the characteristics of a disease. Yet it has not, in my recollection, really been depicted as a disease the way it is in Leigh Whannell's Wolf Man. As opposed to zombie-ism, also transferred by a bite, lycanthropy is more of a mixed blessing, usually seeming to add power and body mass rather than subtraction and submission to a horde. Virtually every piece of zombie fiction that's popular features a character committing suicide, or assisted death, rather than turn undead, but that approach is rare enough in werewolf movies that it's most notable as a suggested course of action in An American Werewolf in London, where it's played for humor.

Perhaps that's because the wolf curse, or sickness, is usually something that only lasts for one night a month, on the full moon, giving the protagonist hope that while human, he can at least mitigate the damage, perhaps by restraining himself on the key night. Inevitably, though, the story usually ends with the werewolf getting shot and turning human in death, a twist that carries over to purely metaphorical, “scientific” werewolves like the Invisible Man or Mr. Hyde. Just as Whannell removed that tradition from his Invisible Man, however, he now offers a take on the werewolf that's based more on David Cronenberg's The Fly than anything from, say, Underworld. Here, the lycanthropy is as plague-based and irreversible as any zombie virus, even as it also heightens the senses.

There's more on his mind than body horror, though. I wouldn't be surprised if this take were somewhat inspired by COVID, but the film outright tells us multiple times, in so many words, that it's about generational trauma. Blake Lovell (Christopher Abbott) had a father who acted like a drill instructor, all in the service of supposedly protecting his kid from whatever it was that caused no mother to be in the picture. The opening sequence, depicting a child Blake and his dad on a hunting trip into woods where all things wicked this way come, is Whannell at his minimalist best, relying on liminal spaces and clever sound design to convey the threat. As in The Invisible Man, he knows he has to show you the scary thing eventually, but the build-up doesn't feel like deliberate stalling or a cheat.

The movie skips ahead thirty years with Blake learning that his father, missing for some time, has finally been declared legally dead, requiring a return visit to the old isolated compound in the woods of Oregon. In a stunningly ill-considered, albeit perhaps necessary decision, he tries to make the whole thing a fun family vacation to restore the ties that bind. Blake and wife Charlotte (Julia Garner) stress each other out – in the movie's most unintentional laugh, we learn that he is an unemployed writer, she a journalist, and they somehow have a massive city apartment. I don't know whether to LOL or break stuff, but I'll probably just keep begging for subscriptions to my personal Substack.1

On the other hand, Blake is a near-perfect dad to young Ginger (Matilda Firth, an English girl convincingly playing American), saying and doing all the right things and apologizing when he should. We get the hint of a temper early on, as he yells at her not to do something unsafe, but he follows that by lecturing himself, in front of her, about how parents can scar you by trying to avoid scarring you. A slightly deeper read of the film suggests this Wolf Man may not just be a metaphor for the abused who end up abusing, but also the superficial “nice guy” who's ultimately a predator. (The Gai-Man, perhaps?)

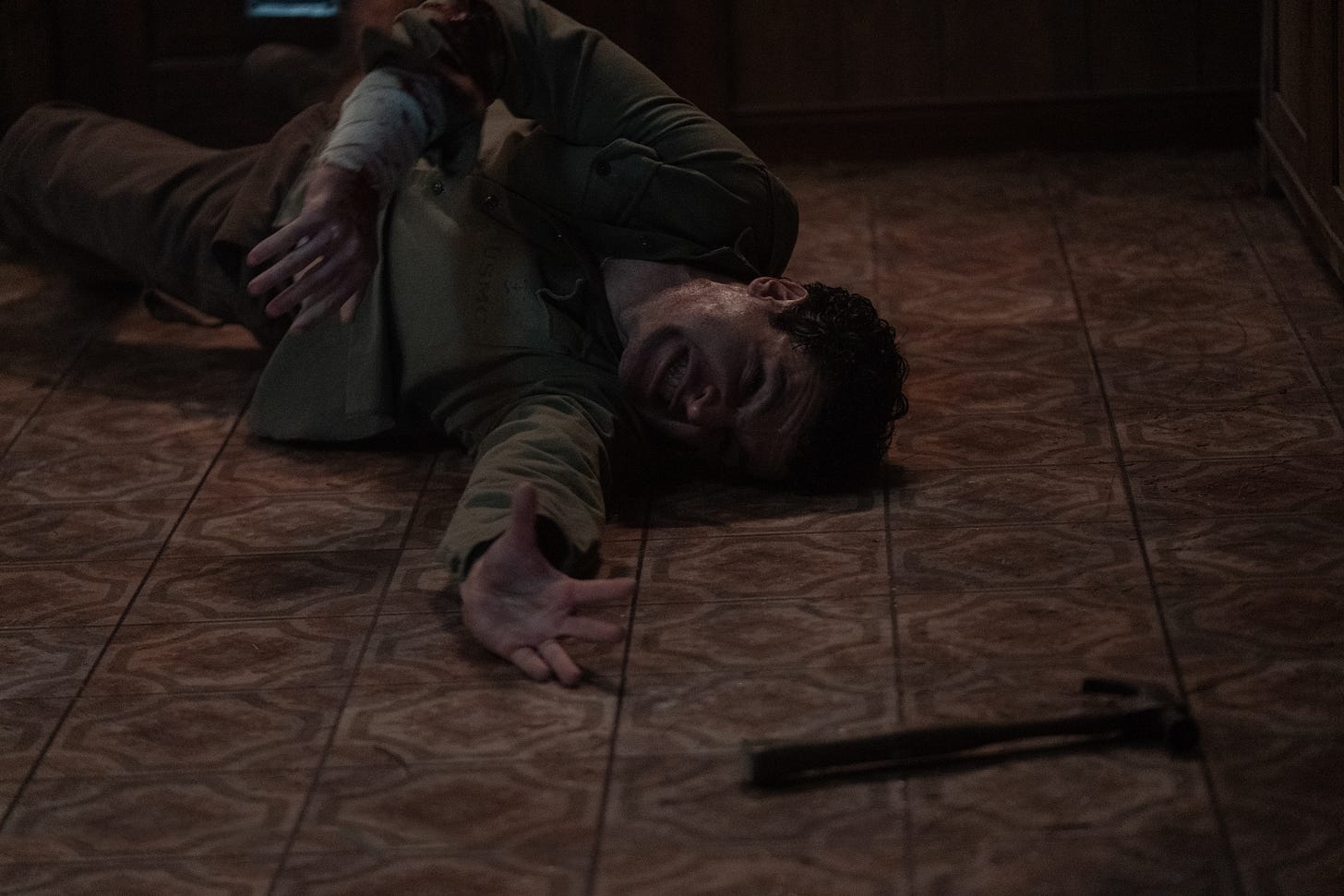

Shit happens, there's a Wolf Man [spoiler!], and Blake gets bitten. About halfway through, we finally get to see what it looks like, and while it's not as terrible as that premature costume from Universal Halloween Horror Nights, it's not totally in a different realm either. I suspect it wouldn't look great in broad daylight, so we never actually see it that way.

The classic Blumhouse formula, in the beginning, had protagonists, usually a family, wandering around a single-house location for the whole movie, trying to find the source of the evil thing doing scary stuff. They find it at the very end, and either prevail or don't. Here, while we have the house and the family, we know the threat, and for much of the movie, it's coming from outside the house, even as Blake begins to devolve into one inside. Again, Whannell does clever things with sound to show the transformation, from making human speech incomprehensible – his family start to sound like characters from The Sims -- to enhancing what Blake hears for one of the movie's most creative fake-outs. Blake also develops his own wolf-vision mode, which is a bit like Predator-vision if Predators lived on planet Pandora and loved shades of blue accordingly.

Classic werewolf mythology is all over the place, but in the form we best know it today, it seems to have loosely come about as a result of zealous Christianity demonizing pagan beliefs, holding werewolf trials as the male version of witch trials, and superimposing evil and Satanic superstitions over tribal legends like skinwalkers and wolfwalkers. An opening text screen nods to this mixed heritage by mentioning Indian tribes who saw the infected and presumed they were wolf-people.

Pagan wolf-people weren't necessarily cursed or bad in the lore, but the classic Universal Wolf Man is a tragic figure, doomed to become an evil monster despite his best intentions (this is true of most Universal monsters, save Dracula, who is unapologetically evil). Whannell's Wolf Man goes out of its way to show how much Blake loves his family so his eventual fall will be all the more tragic, but the director also suggests that dealing with a very sick loved one is its own kind of monstrous nightmare, for both parties sometimes. [Not untrue.]

It's gauche to review other critics' reviews, but some of the general negativity I've seen towards this film appears to stem from knowing too much about the development process2. The average moviegoer won't care that there might have been a version of this starring Ryan Gosling, and it's best not to wonder what might have been, since there'll undoubtedly be more opportunities. [If you think this is the last remake of The Wolf Man you'll see in your lifetime, or even the next decade, bless your heart.] Aside from one hare-brained scheme by Charlotte that's easily attributable to panic, it's a pretty concise story, and the generational trauma theme lends itself to many possible sub-themes – if Bad Dad is clearly a militia/survivalist type, is this also about the political divide? Is Blake a former Biden voter who turned to Trump? If it's borrowing heavily from The Fly (it is), does that make it a metaphor for AIDS too? Does it better apply to fibromyalgia, an auto-immune disease that has some correlation to childhood abuse?

None of that actually matters if it doesn't work as tragic horror first and foremost, and seeing the family bonds deteriorate due to forces beyond their individual control certainly made me feel bad for them. It may also be the first horror movie I've seen in a long time where the family lets their infected loved one inside, and you don't want to scream at them that they're idiots not to kill him immediately. Because there is a legitimate chance that his turn won't be completely feral, and you sense it. I do want to yell at whoever chose that horrible blonde-curls hairdo for Garner that does her no favors – it looks like a bowl of fake spaghetti on her head, though I confess I am not one to blame an alleged journalist for getting a distinctive coif in order to be noticed.

The Invisible Man remains the superior of the two movies, but then the Invisible Man is an intellectual monster while the Wolf Man's a savage. The smaller scale of these movies suits both – horror, generally, isn't served by having the budget of a superhero film. It does tend to require gore, especially from a carnivore, and this Wolf Man delivers plenty, despite its small cast and low body count.

You won't go too wrong with this one unless you're expecting something drastically different.

Wolf Man is now playing in theaters.

I too find this hilarious and want to take a moment to ask you to like and subscribe and consider a paid subscription. — Christian Lindke (Just Kidding, but…)

This reminds me of Heaven’s Gate. The film itself is long, but amazingly powerful. The critics lambasted it, but the critiques seemed so in step with the studio’s complaints that I wondered if it was a PR campaign against Cimino.

I will definitely have some comments on this review, which I think is the most thoughtful review I've read of the movie. I've often said that horror movies try to address society's underlying fears. It looks like this version of the Wolf Man expands the fears it is addressing and might get a bit muddled in the process as it addresses so many. Making horror in an anxious time might be a bigger challenge than in calmer moments.

Lovely review.

I think this could be the kind of horror movie that I enjoy... but this subject matter make it one that I don't think I CAN see; there are some buttons that are just too powerful and personal, and the idea of turning from someone who legitimately cares for their family into the thing that threatens them is one of those fears that really messes with me.

I can see that this would be fertile ground for horror, but man, there are some psychological places I just really don't need to go, no thank you.