The Action Geekshelf: 13 Action Films that Everyone Should Watch

None of my content is behind a paywall, so if want to help me Buy a Book or Game to review please consider visiting my page on Buy Me a Coffee.

What is the Five-Foot Geekshelf?

Welcome to the third in my Five-Foot Geekshelf series where I create lists of 13 entries highlighting what I think are things that every geek should own or experience. These lists aren’t meant to be a comprehensive or “best of” lists, rather they are meant to be starting points. They are meant to include frames of reference that we can use to discuss the category the list represents.

I was inspired to do these lists when I was reading through some old genre magazines last year. I came across a short two article series that ran in the May/June and July/August issues of Twilight Zone Magazine in 1983 entitled The Fantasy Five-Foot Shelf that had some very interesting recommendations and recommenders and I thought it might be fun to attempt a series of lists for all the various parts of pop and geek culture that I love.

The authors of the Twilight Zone magazine articles were themselves inspired by the famous nickname for the Harvard Classics series created by Charles William Eliot when he retired as President of Harvard University. Eliot’s collection of 50 books, which took up approximately Five Feet of shelf space, contained everything that Eliot believed was necessary for a person to read in order to have a “liberal arts” education. Given that one of Eliot’s main efforts as Harvard President was to minimize the status of liberal arts and transform the university experience from a liberal education to a practical scientific research education, you can imagine that Dr. Eliot had some significant holes in the series.

It must be acknowledged that any list, not matter how long, will always have holes within it that anyone with a level of familiarity will notice with minimal effort. Because of this, I am willing to forgive Dr. Eliot for leaving out The Republic of Plato, even if his leaving it out meant that Karl Popper’s analysis became the common opinion of the dialogue for generations. Anyone who has actually read The Republic begins to doubt that Dr. Popper read more than a couple of undergrad papers on the book. I have a great deal of respect for Popper analysis in the Philosophy of Science, but his interpretation of The Republic leaves a lot to be desired.

That’s just my fancy way of saying that my lists, including this one, will have holes in it and that’s where you the discussant come in.

The first two entries in the series were a discussion of 13 Martial Arts films taht belong in everyone’s video/movie library and the second was 13 role playing games from the 1970s I think you should own. As you might guess, I’ll be doing role playing game lists for every decade and for a variety of film genre.

These 13 Martial Arts Films Belong in Your Library

None of my content is behind a paywall, so if want to help me Buy a Book or Game to review please consider visiting my page on Buy Me a Coffee and Buy Me a Book.

Time to Talk About Action Films

This was an amazingly hard list for me to put together for a couple of reasons, not the least of which is that there are so damn many great action films to choose from as films everyone, or more specifically every geek, should watch. I wanted to avoid being an “erm, actually” snob and recommending films like Le Samouraï, which is great but very obscure. I also wanted to avoid recommending films everyone has already seen. “Why yes, everyone should watch Die Hard as a great action film,” isn’t a take.

One of the interesting things about choosing the “Action Film” as the basis for a Geekshelf list is that I had to think about what the definition of an Action Film actually is. Certainly, there have been films with action in them for as long as there have been movies. Edwin S. Porter’s landmark 1903 silent film The Great Train Robbery, had a lot of action and is a major film in the history of editing and how that affects a film’s narrative. The movie was distributed to theaters with instructions that allowed for a shot of an outlaw leader firing at the camera to be placed at either the beginning or the end of the film. Depending on which choice is made, the narrative of the film is slightly different and so is the effect on the audience.

The version of the film that I am sharing includes the shot at the end. I didn’t make this choice for narrative effect, rather because this version is a relatively high quality transfer and the other high quality transfer I added sound effects. Since this was a silent film, any sound effect for gun shots would have had to be created in the theater by the projection team and that would be a live experience based on individual theaters. One thing that is interesting about the Silent Era is how different the experiences of audiences could be due to the use of different scores or because the local exhibitors chose to add sound effects. Such differences in presentation enhanced the “pseudo-environment” of filmic understanding or “pseudo-cultural” influence a film could have.

As much action as The Great Train Robbery has, I don’t count it as a member of the Action genre. To me, it’s clearly a Western, but in 1903 the actual gunfight at the O.K. Corral had happened a mere 20 years earlier and the Joss House Shoot-Out happened in Bakersfield, CA that same year. The Western film wasn’t “Historical Genre Fiction” at the time, it was “Modern Action.” I imagine that at some point, the Modern Action Film will be subclassified in the same way, but that time has yet to happen and so this list will focus on the Modern Action.

In her book The Hollywood Action and Adventure Film, Yvonne Tasker argues that what we now think of as the Modern Action film became a distinct genre in its own right during the New Hollywood movement of the 1960s to 1970s. The action films of that era pulled elements from Gangster films, Westerns, and Film Noir and added a dash of realistic violence to create something entirely new. John Wayne’s early film Stagecoach has action, and influenced later Action films, but like The Great Train Robbery it is a Western through and through.

I asked some of you what your thoughts were regarding the rise of the Modern Action Film and while there was some fuzziness around the edges, most of the responses fit with Yvonne Tasker’s analysis. Retroist thought that the Steve McQueen film Bullitt (1968), The French Connection (1971), and Dirty Harry (1971), helped to set the stage for the genre and I agree and have incorporated some of his logic into the list. Luke Y. Thompson highlighted the importance of Hong Kong films, in particular Jackie Chan’s work, and how that was inspired by Buster Keaton’s films like The General (1926). I’d add to Keaton’s work the efforts of Pearl White in The Perils of Pauline (1914) and Helen Gibson in The Hazards of Helen (1914 - 1917) which took a more melodramatic approach as well as the work of Harold Lloyd whose Safety Last is a banger. Seth Masket offers up Taxi Driver (1976) and highlights the connection between Action films and social commentary, while Ty recommends The African Queen (1951) as a starting point.

While I don’t think Yvonne or the chat has presented the final word on when the Modern Action Film started, I do think it provided a lot of great context and recommendations for those who haven’t seen them. I hope that after reading my list of 13 “Essential” Action Films, you’ll make your own offerings and I hope that you’ll contribute your own thoughts regarding when the genre finally became its own distinct media genre.

So…here are my 13 movies in a list that starts with “proto-action” and ends in full Modern Action. I’m not going to try to be intentionally obscure with the list, but I won’t be including only movies that I know everyone has already seen either. I’m sure that some of my proto-action films might not meet your definition of action, but to me they are quintessential to the development of the genre. At some point, I’ll likely write a post discussing how the Modern Action film, as developed in the US, is a natural development of the dime novels of the 19th century, the pulps of the 20s and 30s, and an extention of the “Men’s Adventure Magazines” that my friend Bill Cunningham has been attempting to revive for the past few years through his company Pulp 2.0 Press.

The Modern Action Five-Foot Geekshelf

1) The Narrow Margin (1952)

Richard Fleischer’s (with additional scenes by William Cameron Menzies) film The Narrow Margin is often classified as a noir film, but I’ve never thought of it as fiting into that genre. While it deals with the darker elements of humanity, as is the cornerstone of noir, it is an overall optimistic film. It is a film about good triumphing over evil and lacks the moral grey of a true noir film. I’d argue that the film is in many ways an anti-noir film. When I think noir, I think of films like Double Indemnity with it’s commentary on greed or In A Lonely Place with its commentary on trust. Where Double Indemnity shows how a great villain (thanks Barbara Stanwyck) can corrupt the seemingly innocent, In A Lonely Place shows that a noir tale needs no villains, it only needs the characters to perceive each other as vile.

The Narrow Margin is in the school of the Hard Boiled tale where the White Knight (the Continental Op for example) has a hard edge, but is still a man of virtue. To quote the Op in The Dain Curse when he described himself. He said he was, “"A monster. A nice one, an especially nice one to have around when you're in trouble, but a monster just the same, without any human foolishness like love in him, and--What's the matter? Have I said something I shouldn't?"

In the case of The Narrow Margin, that White Knight has a particular charm. I’m not going to reveal who the White Knight in the film is, or how that subverts the noir just as the Op subverts it in The Dain Curse, instead, I’ll touch on why this is a key proto-action film. There is a nice balance of stunts and tension in the film that allows for bursts of action within a normally innocent environment. The setting isn’t a battlefield, it’s a train and it establishes a number of tropes (or at least solidifies them) that have influenced Narrow Margin (a remake by Peter Hyams starring Gene Hackman), Under Siege 2: Dark Territory, and the Mission Impossible Franchise. It uses the unity of speace very well.

Charles McGraw is very good as Det. Sgt. Walter Brown and Jacqueline White is solid as Ann Sinclair, but it is Marie Windsor as Frankie Neall who really steals the show. Windsor is one of the great femme fetales of classic Hollywood.

2) Magnum Force (1973)

When discussing the origins of the Action Film in the Geekerati Chat, Retroist mentioned both Bullitt and Dirty Harry as early examples of the genre. They are both excellent films, and you should watch them, but I left both of them off the Geekshelf because they are both tangentially inspired by Dave Toschi, the real world SFPD officer who investigated the Zodiac Killer in the 1960s and 1970s. One could probably do an entire Toschi geekshelf that would include Bullitt, Dirty Harry, Zodiac, The Hard Way, Star Wars (Tosche Station), and So I Married an Axe Murderer. Additionally, both Bullitt and Dirty Harry are in a gray area between police procedural and action film with both falling a bit more in the police procedural circle of the Venn Diagram that includes police procedurals and action.

Magnum Force though is when “Dirty” Harry Callahan shifts from being a “cope on the edge who pushes the boundaries of the system” to a “lone wolf fighting directly against elements of the system he inspired.” Magnum Force engages directly with the critics of Dirty Harry by providing cops who represent what some critics argued Harry stood for and then having Harry gun them down because they would otherwise be above the law. A similar idea had been proposed by Terrence Malick (yes, THAT Terrence Malick) in his early draft for Dirty Harry and this time John Milius (one of the most important figures in American action) and Michael Cimino (dear God this film is stacked with literary talent) are the screenwriters and Ted Post (Hang ‘Em High and Good Guys Wear Black) directs. I was really happy to be reminded that Post directed both this and Good Guys Wear Black because I think that’s a quintessential action film too, but I included it under essential martial arts films (above) because it was revolutionary in the evolution of that genre in America.

The film stars a pre-Starsky and Hutch David Soul, a pre-S.W.A.T. Robert Urich, and a Tim Matheson seeking to differentiate himself from his Jonny Quest/Yours, Mine, and Ours squeaky clean image.

3) Smokey and the Bandit (1977)

Burt Reynold’s was already a star by 1977 having starred in the proto-action films Deliverance, White Lightning, The Longest Yard, and Gator, but Smokey and the Bandit launched him into the stratosphere. The movie made $127 million in the box office (in 1977 dollars, so that’s around $500 million today) on a budget of $4.3 million ($17 million). Let’s say that any time you make a return of 29 times the investment, that’s a tremendously successful film.

The movie also ramped the action up on the bootleg/heist film by incorporting an extremely well edited and paced 60 minutes (at least) of chase sequences. The movie is very much a product of its era. You are getting the undiluted 1970s in every moment of dialogue, from the sexual politics to the use of CB slang to the post-civil rights distrust of local law enforcement. It’s the alcohol film temporal experience of drinking everclear straight. Speaking of the post-civil rights distrust of local law enforcement film, I’m definitely going to have to do an “Evil Sheriff Geekshelf.” It’s one of my favorite genres and while this film will have to be excluded from that list, because it’s in this one, Smokey and the Bandit is a quintessential entry in that genre.

This makes the Action Geekshelf because this film, more than most action and proto-action films of the 1970s and earlier, leans heavily into incorporating humor and that is a central component of a lot of modern action. From the one liners of many action heroes (also inspired by Bond films) to the quips in Die Hard, comedy has become a big part of action film DNA and this film sets the formula. It also breaks my cardinal film rule that “every male screenwriter has a hiest screenplay they want to write…and it should never be made.” Director Hal Needham started his career as a stunt double for a number of actors, including Burt Reynolds, before he directed this film, which in its own way makes this film the John Wick of its era. By which I mean a film directed by a stunt man/stunt coordinator that reinvents what action can be on the screen. Burt Reynolds balances his charming and goofy personalities perfectly in this film, something he rarely managed in later films, and Sally Feed, Jerry Reed, and Jackie Gleason are fantastic. One thing that really stands out when watching Smokey and the Bandit today is how tight the script and action are. There is no shoeleather and yet the film is as much a character driven comedy as it is an action film.

4) The Warriors (1979)

Director Walter Hill is one of the most important and influential directors in the development of the modern action film and because of that I included him twice on this list. I intentionally avoided recommending 48 Hours, even though it is really a canonical action film that everyone should see, because they probably have already seen it. Hill’s action film cred includes writing the screenplay to Sam Peckinpah’s The Getaway (which along with Straw Dogs almost made the list), being an uncredited writer on Alien, directing The Driver, The Long Riders, Southern Comfort, Red Heat, Last Man Standing, Wild Bill, and the pilot episode of Deadwood.

Hill captures the grit that Quentin Tarantino aimed for in Reservoir Dogs, The Hateful Eight, and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, but without the over the top elements that Tarantino adds. Hill’s films can be absurd from time to time, but they are always grounded in a kind of realism that adds depth to the characters. His 1979 film The Warriors is an adaptation of a book by Sol Yurick that takes the tale of Xenophon’s Anabasis and updates it to late 1970s New York. If you want to read a good historical novel based on the Anabasis I recommend Michael Curtis Ford’s The Ten Thousand. I also recomend reading The Landmark Xenophon’s Anabasis (because MAPS!), Leo Strauss’s On Tyranny (which contains a translation of Xenophon’s Heiro), and Xenophon’s The Education of Cyrus (the Ambler translation is very readable). And yes, the fact that I got interested in Xenophon is entirely due to watching The Warriors with my grandfather as a kid and finding out later that it was inspired by a real event.

The Warriors is an extremely influential action film as it takes us out of the world of police procedural, or competant loner, and into the realm of people desperately trying to get home. It’s a pattern that has repeated in many lesser action films, including Judgement Night. The film is also influential for the way it presents a hyper-real gangland version of New York (no-one thinks the Furies are a real gang, but they are still really cool and very scary) that allowed it to engage with real anxieties of the time. There are some gangs in the movie that are more realistic than others, but the inclusion of the surreal ones never detracts from the verisimilitude of the film. It “feels” real, even as you know you are watching a fantasy. The first John Wick film, captures this kind of secret world fantasy realism perfectly and the later films use that introduction to allow us to journey further into the world. The film also has something to say about “America” as a concept and The Warriors are that representation, even as many of the gangs represent groups that have a vision of what America should be. There’s philosophy in this film beyond that in the foundation.

5) First Blood

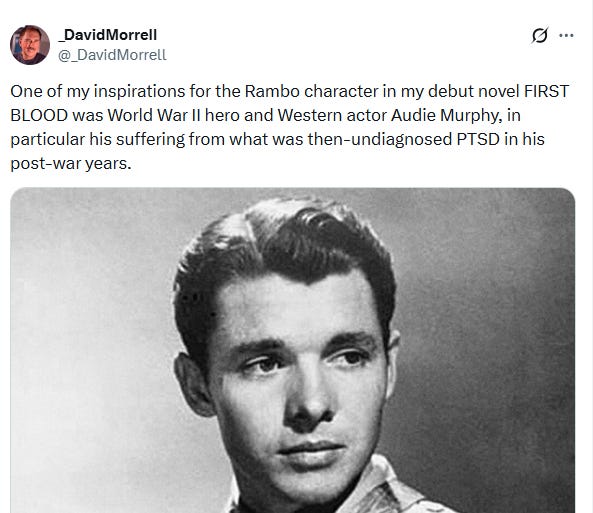

The “corrupt Sheriff” subgenre of action films is probably worthy of its own list of films and it’s one of my favorite subgenres. From the humor of Smokey and the Bandit, the absurdity of James Garner’s Tank, and the conspiratorial Jack Reacher, to the political commentaries of Billy Jack and the recent Netflix film Rebel Ridge, it’s a genre that appeals to people on the political Left and Right of the spectrum. One of the films that best encapsulates how this genre appeals to the full political spectrum is First Blood. Directed by Ted Kotcheff (Uncommon Valor, Weekend at Bernies…you read that right) and starring Sylvester Stallone (Rocky and c’mon this is Sylvester Stallone we are talking about), First Blood was based on David Morell’s book about a troubled Vietnam veteran who is harrassed and abused by a small town Sheriff.

Morell was inspired to write the story by stories he heard of the experiences of students he had who fought in Vietnam and by the post-war life of World War II hero Audie Murphy. Though Murphy is the most decorated soldier in American history, and though he starred in many films, he suffered from severe Post Traumatic Stress and spoke about his experiences to draw attention to problems service members returning from Korea, and then Vietnam, were facing. First Blood is important as an action film (it did become a franchise after all), but it is important for the very real way it dealt with Post Traumatic Stress. It’s a topic often avoided in action films, though it has been touched on in films like The Best Years of Our Lives and The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (the book by Sloan Wilson is even better).

6) Point Blank

John Boorman’s film Point Blank adapts Richard Stark’s novel The Hunter, about a crook named Parker who is betrayed by fellow criminal who wants to get the money he earned in a big score years back. Stark’s Parker is the Mirror Universe version of your typical pulp action hero. He’s the anti-Continental Op, the goateed Philip Marlowe who lacks a traditional moral code. Yet, he does have a code and if it’s violated, those who betray him will be much the worse for wear.

As is typical of Parker adaptations, Parker has been renamed. This time as Walker, but later when Mel Gibson stars in an adaptation of the same story as Porter. I don’t know why they don’t use the character’s real name. Then again, when they have (I’m looking at you Statham), the results aren’t as good. In Boorman’s film, the setting is shifted from New York to Los Angeles and I think this is a brilliant choice. To me, Los Angeles is the “noirest” of cities. Like New York, it is a place where people move to fulfil their dreams, but if things go wrong in New York, the trainride back to Hoboken is short and you probably won’t be able to afford a trainride home from LA. The myth of Hollywood entices people with bright glittering lights, only for those people to find out that the neon lights of Sunset Blvd. are a nuisance as they interrupt your attempts to sleep in the trash strewn alleys.

Obviously, that’s an exaggeration of the grit of Los Angeles for most people. It is, in fact, my favorite city, but it is a city where hope can go do die. As the song Hotel California goes (there’s the urban myth that it was inspired by Camarillo State Hospital just outside the city which has now become Cal State Channel Islands), “you can check out, but you can never leave.” There’s a bit of that not being able to leave in Point Blank and the tension and darkness of the film are palpable. The final confrontation in San Francisco in this film should remind you of the end of John Wick stylistically.

7) Streets of Fire

When I mentioned that Walter Hill had two movies on this list, you were probably wondering what the second film was. It’s Hill’s surreal post-apocalyptic pseudo-1950s musical fantasy action fairy tale Streets of Fire. This is one weird movie, but its one that grows on the viewer the more times you watch it. It stars a young Diane Lane who demonstrates her same ability to captivate the audience as a rock star as she demonstrated in Ladies and Gentlemen: The Fabulous Stains, as well as a scenery chewing Willem Dafoe as the movie’s main antagonist Raven Shaddock.

Screenwriter Larry Gross said that when he and Walter Hill were working on the film, Hill told him he wanted to make a comic book movie without the source being an actual comic book. Streets of Fire is the kind of film that demonstrates that genres can break type while still remaining true to the tropes. A lot of people say that the death of the American comic book is largely due to its focus on Superhero stories and that Manga are crushing them because they are about anything, which doesn’t acknowledge that even Superhero Manga outperform American comics. It isn’t that American comics focus on Superheroes that is the problem, it is the “how” they do it that’s killing them and for that I blame the British invasion and a desire to be “literature” rather than entertainment.

Hill wants Streets of Fire to be raw entertainment and it is. The songs are bangers. The world is a truly dystopian alternative 1950s, what would now be called Dieselpunk (except unlike most things called x-punk this actually has punk elements). Except for the fact that Hill had just made 48 Hours, I don’t see how this got made. It’s too out there. It is fantasy, but not in the way most people would expect it, just as it is a Superhero story without us being any the wiser.

8) Big Trouble in Little China

A big part of the development of what has come to be the traditional American Action film is the influence of the Hong Kong film industry on American directors. I’ve covered this a bit in my Martial Arts Geekshelf (above), but it’s important to note that at almost the first opporunity Burt Reynolds brought Jackie Chan into his Cannonball Run franchise and that Chuck Norris, who worked in Hong Kong before becoming big in America. Hong Kong’s film industry took American ideas, added their own mix of things, and then dialed them to 11. They were also telling their own stories, including adapting wuxia tales like Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain. Zu is one of the best wuxia films ever made and its story and style influenced the look and feel of Big Trouble in Little China, just as Jackie Chan’s Police Story movies would influence Amerian contemporary action films to higher and higher heights of action.

Big Trouble in Little China does something else too. It inverts the hero and the sidekick characters. Though the film stars Kurt Russell in the “lead,” the real hero of the film is Dennis Dun’s character who goes from nice guy, to talented martial artist, to fighting one of the Three Storms in a duel to the death. As Kurt Russell states in the DVD commentary, “We would flip flop the leading man and the sidekick, and the sidekick would act like the leading man and the leading man would act like the sidekick but not know it.”

The inversion was intentional and it is magnificent. Though the film was a box office flop, it has developed a cult following over the years. More importantly, it has gone on to influence a ton of later American action films through its balance of action and comedy.

9) Armour of God (1986)

Just as Hong Kong films have influenced American films, so too have American films influence Hong Kong productions. Take for example Jackie Chan’s take on Indiana Jones (Asian Hawk), the main character of Armour of God, Armour of God 2: Operation Thunderbolt, and CZ12. The Indiana Jones franchise contains a number of wonderful stunt set pieces, but Armour of God takes stunts to the next level and Jackie Chan nearly died in the production. Ironically, his severe injury came during one of his less dangerous stunts in the film.

Armour of God tells the story of Asian Hawk, a treasure hunter, who gets blackmailed by an evil cult into acquiring the final piece of “The Armour of God” that they will use to some nefarious end. Hawk and his allies then proceed to find the Armour and… well, no spoilers. The stunts in this film are next level and I’m particularly fond of the final set piece. The film was directed by Jackie Chan and Eric Tsang and stars Chan, Rosmund Kwan, and Alan Tam. You can see influences from this film in all kinds of places, including Hudson Hawk and the first Tomb Raider film as well as the Mission Impossible franchise. It is hard for me to think of Ethan Hunt without imagining Jackie Chan in the Tom Cruise role.

9) La Femme Nikita (1990)

What is my favorite depiction of a female assassin trained in ballet? The answer to that question is Luc Besson’s classic film La Femme Nikita. While there have been hundreds of movies inspired by this French actioneer in the decades that have followed, very few have had the real heartfelt romance at the core of this movie. The love between Nikita (Ann Parillaud) and Marco (Jean-Hugues Anglade) is subtle, sweet, and very real. They are absolutely charming together, which is what makes the movie all the more powerful when the masturful Tchéky Karyo shows up to disrupt everything.

Luc Besson has made a lot of movies I’ve enjoyed over the years, but he has rarely captured teh wonderful emotional balance that he found in this film. In later films, he focuses more on his very capable ability to capture action. In Nikita, however, he balances the beauty and subtlety he brought to The Big Blue (watch this movie now) into an action film and it makes it all the more magical. While some of the influence of the film is obvious (Anna, Hanna, Ballerina/John Wick). Yes, there’s a dash of Black Widow in La Femme Nikita, and Natasha definitely inspired Besson, but the assassinations here are removed from the Cold War tensions of the early Widow stories and though there is romance in Natasha’s past, it isn’t with the goofy grocery clerk. There is a suburban element to Nikita that is new and fresh and I think is behind a lot of the modern “suburban secret assassin” movies of late.

10) Hard Boiled (1992)

Just as Bruce Lee changed the way Hong Kong martial arts films were choreographed forever after (and eventually American martial arts films), the action film was never the same after John Woo’s run of films from 1986 to 1992. His films, ranging from A Better Tomorrow (1986) to The Killer and Hard Boiled, took the visual style of William Friedkin and meshed it with martial arts choreography and symbolism pulled from Christianity and Opera. In doing so, Woo changed the visual dynamic of all action films. While there was a brutal beauty to action films that followed Sam Peckinpah’s dance of destruction style, Woo turned the dance metaphor into reality. He storyboarded not only the overall action, but beautiful artistic still images that were at contrast with the violence. Peckinpah influenced violence was raw and challenging to look at. Woo’s was raw and aesthetically beautiful. When Tequila gets revenge for the shooting of his partner in the opening scene of Hard Boiled, he rolls over a table covered with flower and in doing so becomes an enraged Angel of Death.

Visual metaphors are everywhere in Woo’s films, so much so that even I have to acknowledge them. I’m the kind of professor who pushes against New Criticism with its focus on symbols and challenges students to look beyond the Green Light in The Great Gatsby, but in a Woo film I fully embrace the intentional insertion of symbols as having deeper meaning. Hard Boiled is a combination of Pulp and Noir (they are not the same) where the main protagonist is the White Knight of Hammett or Chandler, but the secondary protagonist is straight out of Criss Cross. Visually the film is a masterpiece and the acting is top notch. It is one of the best action films ever made and it demostrates that a film can be made up of largely action scenes while still having great narrative depth.

11) Rapid Fire (1992)

Where Hard Boiled showed how Hong Kong was transforming the American action film for the better, Brandon Lee’s Rapid Fire (1992) and The Crow (1994) demonstrated the influence Hong Kong films were having on American action films. As talented a martial artist as Chuck Norris was, the choreography in his films was often hindered by the lack of talent on part of directors and stunt choreographers. In the scene in Good Guys Wear Black (Norris’s best film narratively) where he is fighting a number of opponents in a parking lot, Norris is so much faster and dynamic than his opponents. He’s having to hold back, and even then they flinch instead of perform. John Carpenter’s Big Trouble in Little China upped the choreography game, but Brandon Lee made it truly shine.

Brandon Lee’s fight with Al Leong, one of the few stunt player/henchmen actors who is amazing enough that an entire generation knows his name even though he was never a lead (he’s also super nice in person), is one of the best fights of the era and Lee’s acrobatics show that America was ready to embrace what John Woo was cooking up in his films. If you look at the strikes and kicks used in this fight, they aren’t what audiences were used to seeing. There are kick blocks and grapples. You have a combination of choreography and realism that would come to define later action films and the moments when Lee uses center line based strikes is a wonderful homage to his father. The story is simple, but the action is a blast and Lee’s acting is vastly improved from Showdown in Little Tokyo. Had he lived longer, Lee would certainly have been a major action star.

12) Desperado

With El Mariachi, Robert Rodriguez demonstrated that a great action film could be made on a budget. With Desperado, he demonstrated what a talented budget conscious film maker could create when given a budget. Combining the beauty and dance choreographic style of John Woo with the raw feel of Mexican films and Spaghetti Westerns, Rodriguez created something truly special.

Robert Rodriguez combines mythic elements, such as the Steve Buscemi storytelling moments, a dream song performance inspired by Chuck Norris’s fight in Forced Vengeance. Where the Chuck Norris film was prosaic enough in general that it almost didn’t deserve the aesthetic beauty of the shadows fighting in front of the Coca-Cola sign, Desparado’s musical number shows how much attention to visual will be paid throughout the entire production. If you want to know what happens when you mix Roger Corman, Sergio Leone, and John Woo, it’s Desperado and it is a thing to behold.

13) The Night Comes for Us (2018)

No conversation of the modern Action film would be complete without discussing the impact Indonesian action films have had on the modern American film industry. Joe Taslim and Iko Uwais amazed audiences with 2011’s The Raid (and Uwais features in the underrated Keanu Reeves directed film The Man of Tai Chi). I often joke that The Raid and Dredd (2011) are the same movie, because they are narratively very similar, but the films were directed simultaneously and half a world away from one another. Both of those films are must watch action films that add to the depth of the genre. Dredd for its excellent use of suspense and The Raid for its continued escalation of action and threat. Dredd shows how good a “low” stakes superhero movie could be, while The Raid demonstrates how the Indonesian action industry is pushing action beyond even the extreme levels that Hong Kong pushed them in the 1990s.

As far as The Raid pushes those boundaries, The Night Comes for Us makes that boundary pushing look like a nudge. Where John Woo films showed us what happens when you combine Sam Peckinpah levels of violence with the beauty of Fred Astaire/Gene Kelly dance numbers, Uwais and Taslim show us what happens when you combine John Woo with Eli Roth. The Night Comes for Us is the first movie I ever watched that I was exhausted after viewing. This fight between The Operator and Alma & Elena is a perfect example. It starts relatively simple, a little slow even. Then it escalates and soon you’re seeing a little body horror and you have to remind yourself that this is an action film and not horror.

My heart pounded from the tension of the action, the brutality of it, and the potential despair I might feel if the film turned out to be a tragedy. The film borrows many elements from Noir, but the ending is one from the Pulps. It is sad, powerful, but not painful. The brutality is hard to watch, even as it is mind bogglingly amazing. So much is done with practical effects that your stress is not only for the characters in the film, but for the performers as well. While Uwais, rightfully, has seen some success in the American market with The Man of Tai Chi and Wu Assassins, I’d like to see Taslim get a leading role in an American action film.

So…That’s My List

I’ve included 13 films that I think are essential viewing, but there are so many great action films. What films do you think are “must see” films for any Geek’s Video library?

Great list. I have seen several movies on your list. Definitely will have to see the ones I haven't seen. I was happy to see "The Warriors" on your list. I think it is a great movie. I really should get a copy of it if I can. Another great one I liked on your list was "Big Trouble in Little China."

Great list, Christian! Concur with pretty much all of the entries. I might swap out Point Blank for the The Getaway (1972) which is better IMO, but Point Blank is a good movie, too. And Magnum Force is definitely the BEST Dirty Harry movie - it is head and shoulders above the first one, which suffers a bit (in retrospect) from some very bad acting by almost the entire cast except Eastwood. Magnum Force however, as you rightly point out, has great performances across the board. And it's themes hold up incredibly well - we certainly don't ever have to worry about police death squads in the US, do we? 😑