13 Role Playing Games from the 1970s You Should Own

The Five-Foot Geekshelf Returns

Let’s Start Building Your RPG Geekshelf

Welcome to the second entry in the Five-Foot Geekshelf series! This time around, I’ll be discussing 13 important role playing games from the 1970s. A couple of them are extremely obvious choices. Of the two most obvious choices, only one is played using a rules set that is almost unchanged from its original publication. If you’re a fan of that game, you already know which one I am referring to and how revisions to that game have been rejected even as the original rules have been republished again and again.

The 1970s are a particularly important time in the development of role playing games. Not only was it the decade in which they were first published commercially, but it was a decade of do it yourself mentality that has ebbed and flowed in the hobby ever since. The 1970s were a time of mechanical and genre innovation within the medium of role playing games and it was probably the only time when, depending on geography and convention attendance, you could own almost every game on the market without filing a second mortgage.

I was inspired to do the Geekshelf sereies when I read the two article Fantasy Bookshelf series that ran in the May/June and July/August issues of Twilight Zone Magazine in 1983. The articles were named after the nickname given to the Harvard Classics series created by Charles William Eliot when he retired as President of Harvard University. That collection of 50 books, which took up approximately Five Feet of shelf space, contained everything that Eliot believed was necessary for a person to read in order to have a “liberal arts” education. Given that one of Eliot’s main efforts as Harvard President was to minimize the status of liberal arts and transform the university experience from a liberal education to a practical scientific research education, you can imagine that Dr. Eliot had some significant holes in the series.

I’ll be limiting my 1970s recommendations to 13 entries, rather than 50, so it will likely have more than a couple of holes that more than a couple of collectors will highlight. I’m going to present these in chronological order, rather than order of importance, because I think that’s logical and because outside the first entry any weighing of importance would be entirely subjective.

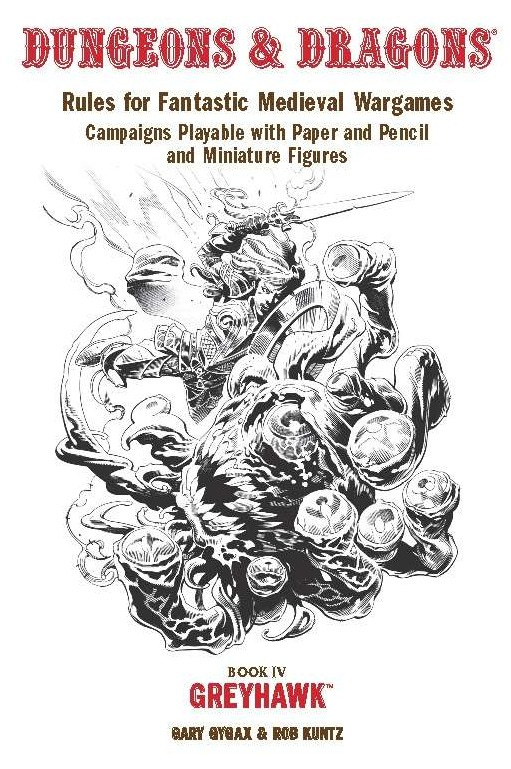

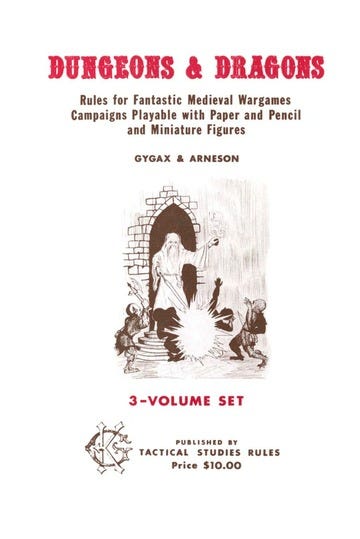

Chainmail (1971), Dungeons & Dragons (1974) & Dungeons & Dragons: Greyhawk (1975)

I’m not going to dive to deep into the recent “Did Gary Gygax, Rob Kuntz, and crew used Chainmail when they played Dungeons & Dragons” discussions in this post. I have thoughts on the issue that I’ll expand on later, but they can be boiled down to the following:

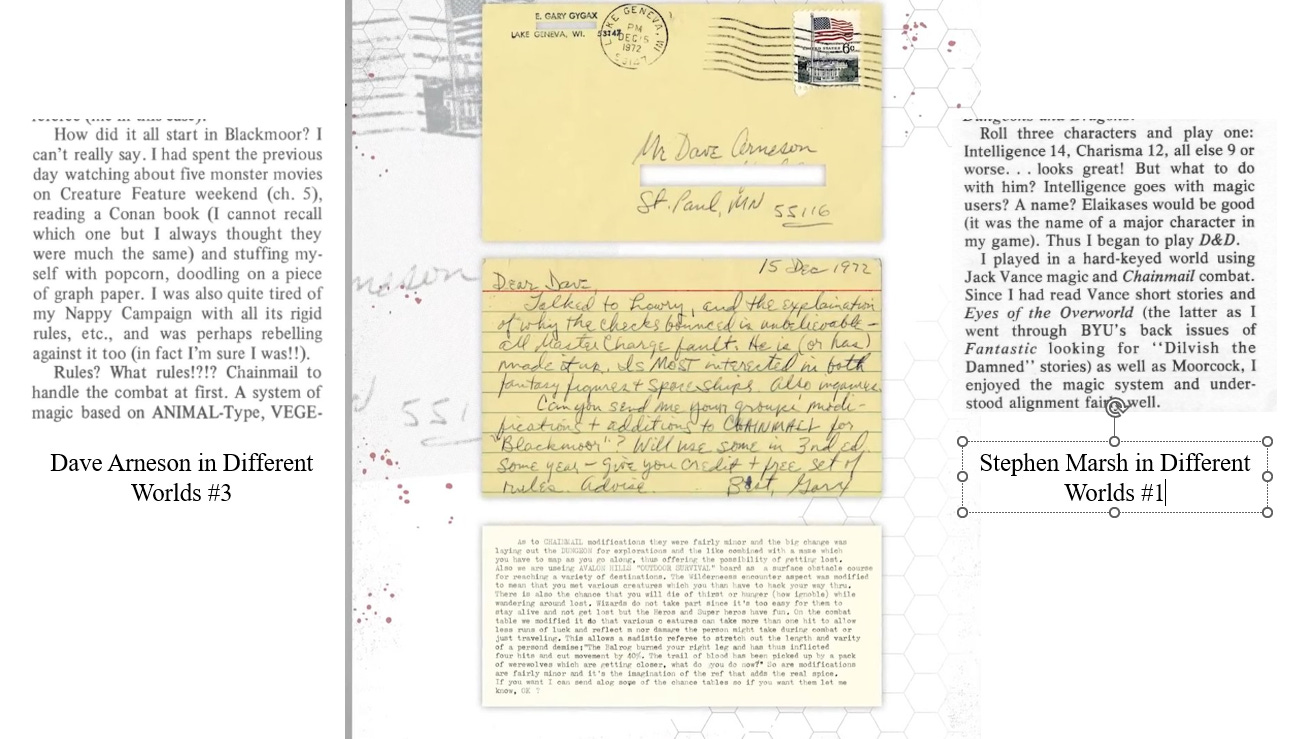

Dave Arneson in 1979 describing the development of Blackmoor and D&D in Different Worlds #3 states he used “Chainmail to start” for combat rules. He also makes it clear that Blackmoor predates that adoption.

Now does that mean that Rob and Gary fought the 4 Balrogs they fought in their first D&D encounter using Chainmail rules? No. (You can read Rob Kuntz’s description of that encounter in Wargamer Magazine #1 or a discussion on my Substack https://geekeratimedia.com/p/gary-gygaxs-first-d-and-d-like-experience?r=1gzmr).

I like Rob and have supported his work since his Pied Piper Publishing self publishing days, but my sense is that the development of D&D went something like this.

a) 1970-ish Blackmoor -- Arbitrary and changing rules by Arneson inspired by old monster movies on local TV station and prior Braunstein play. Official advertisement for these is in May 1971 issue of Corner of the Table Top (see link for Daniel Hobbs’ research. Since he’s the one who wrote rules used by current Arneson products based on his research, I figure the Arneson crowd will respect his timeline).

b) 1971-ish Chainmail — Incorporation of some elements of Chainmail for combat. This is based on Hobbs’ research and sharing of Dave Megarry’s character sheets. Arneson affirms this in Different World #3 and it is further verified by Gygax asking for his revisions in the postcard.

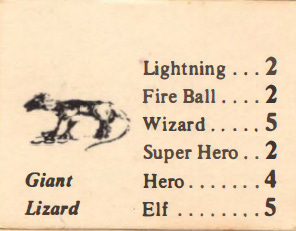

c) 1971 - ish. Design of Dungeon! Boardgame by Dave Megarry (his character sheet for Blackmoor is linked above) which clearly is inspired by Chainmail. You can see the influence of Chainmail in the target numbers on Monster Cards. The “Superhero, Wizard, and Hero” references are straight Chainmail.

d) Frustration with Chainmail’s die mechanics (though Chainmail’s initiative system is D&D’s initiative system until Eldritch Wizardry) leads to creation of Alternate Combat System and this is the system that Gygax and his team always used when they playtested. Chainmail’s influence is there in AC etc. (see Daniel Bogg’s discussion on that here).

You can see throughout the expansion books of D&D that it’s rules were constantly changing and at a radically quick pace. Eldritch Wizardry’s systems are gonzo and arcane.

That said, I think the character sheets, the post card from Gygax asking for Arneson’s modifications to Chainmail in 1972, and the fact that the LBBs say that combat works as in Chainmail with modifications, show that they intended some portion of Chainmail to be used (mostly the initiative system).

D&D in the LBB stage was not a finished game. It was a game akin to Tony Bath’s Medieval Rules. It was playable, but required DMs to design their own answers to a host of dilemma. By the time Greyhawk is published, it is becoming a complete game, even the Holmes Basic set isn’t a complete game yet (given the Daggers problem). It’s not until AD&D and Moldvay/Cook/Marsh that we get two solid and complete games that are each based on D&Ds LBBs.

They are evolutions from that game, but so too is Jason Vey’s aka ElfLairJasonTLG work on playing with Chainmail and his ORC system. Both of which predate modern Chainmail revisionists by over a decade.

Setting aside all of that, very contested and controversial, stuff. It is undeniable that you can play a very interesting game using Chainmail and the Original Little Brown Books of D&D and that you can play an equally interesting and different game using the Little Brown Books and the Greyhawk Expansion. All of those are D&D that someone was playing and in early D&D circles, there was a ton of misinterpretation of the rules too, but that is a tale for another time.

I’ve written about Jason’s work here:I’ve written about Gygax’s first D&D session here:

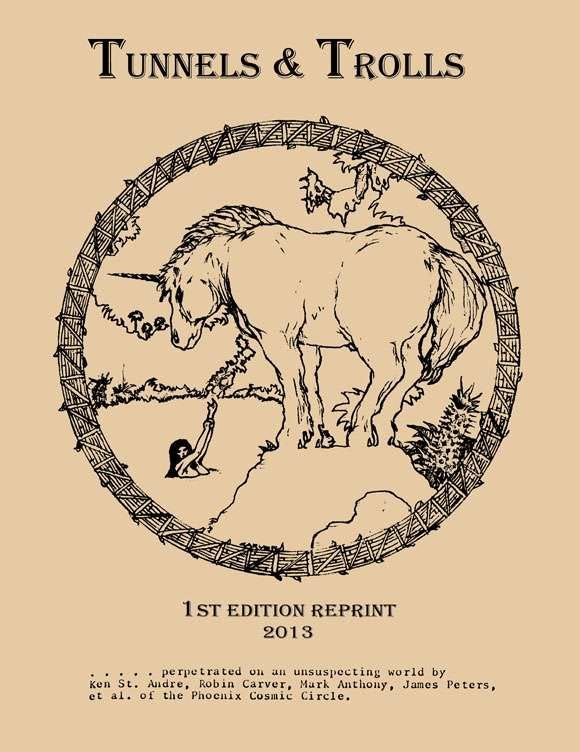

Tunnels & Trolls (1975)

When Ken St. Andre’s friends told him about a newly released game inspired by the fiction of Edgar Rice Burroughs and Robert E Howard, he jumped at the opportunity to learn the rules and run the game for his friends. There was only one problem. The rules were arcane and hard to understand. St. Andre couldn’t figure out how to run the rules as written for his friends and so he created his own rules set that was inspired by what he read in the D&D rule books.

His friends called his game Dungeons & Dragons at first, but once they realized they were playing a game of Ken’s creation he proposed calling it Tunnels & Troglodytes. They rejected the name and recommended Tunnels & Trolls and that was one of very few major changes in the rules in the past 50 years.

You can see the influence of D&D on Tunnels and Trolls’ mechanics. There are physical and mental attributes that are determined by the roll of 3 six-sided dice and the names are very similar to those in D&D. There are classes, levels, and saving throws. Many of the trappings are there, but the game is fundamentally different because it uses only six-sided dice to determine all actions. The combat system uses handfuls of them and the “saving throw” system uses a roll of two of them. If you squint really hard, you can see a player attempting to understand the original combat system of D&D (which is d6 based) and creating a die pool system.

T&T has an elegant system that incorporates a couple of major innovations. It has a spell point magic system, “exploding” dice on saving throws, and a proto-stat based task resolution system. The game is far more influential than it is often given credit for being and like D&D, it was a truly DIY product.Traveller (1977)

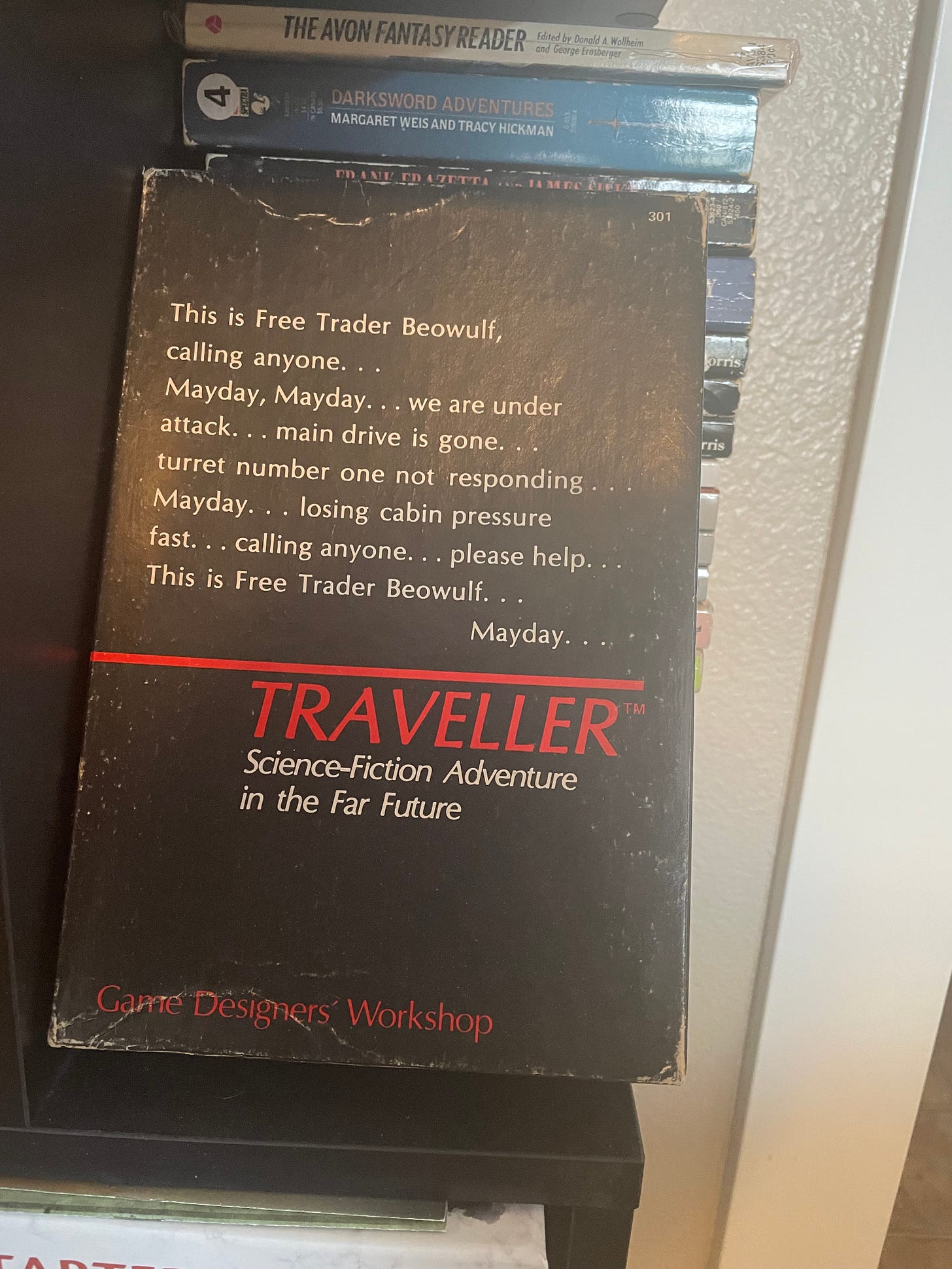

Traveller may not be the first science fiction role playing game, that’s either Metamorphosis Alpha or Starfaring which its own rabbit hole, but it is the first widely successful science fiction roleplaying game and one of the most influential role playing games ever designed. I wrote a farily detailed discussion of the tone of Traveller in May, but here I’d like to focus on a couple of the key innovations in the mechanics of the game.Traveller was the first role playing game where player characters started out with detailed backgrounds determined during the character creation process. Players roll basic statistics for their charactes (using 2d6) and then choose a career path. They have to qualify for that choice or else settle for a lesser choice and they can even die during the 4 years of life that this choice represents. That’s right, your character can die during character generation in Traveller. As Mike Pondsmith lamented when he played Traveller, it was easier to die in character creation than in actual game play. This led to him creating his own “interlock” system that formed the foundation of games like Mekton and Cyberpunk.

The lifepath character creation system wasn’t the only innovation Traveller had to offer. It’s other key contribution was the formal creation of a Target Number based skill system that was easy to understand and that bridged the gap between chit and map wargames and role playing games. Where D&D mechanics where influenced by miniature wargaming, Traveller was influenced by chit and map wargaming and you can see that in the frequent use of DM throughout the rulebooks. In this case, DM doesn’t mean Dungeon Master, it means Die Modifier and was a common abbreviation in Avalon Hill and SPI games.

Traveller also had rules for ship and planet creation and the most recent version of the rules are almost identical to the original release. Like Tunnels & Trolls this game has been remarkably stable in design. Unlike Tunnels & Trolls, it has a very large fanbase.Superhero 2044 (1977)

I’ve written a fairly extensive discussion and review of Superhero 2044 and I believe that it is one of the most important role playing games to ever be published. Not only did it expand the genres covered in role playing games to include superheroes (inspired by the campaign run by science fiction and fantasy author John M. “Mike” Ford), but it provided an interesting cohesive combination of setting and mechanics.The core rulebook may be brief, but it includes a fully flushed out setting for play. Earlier games had implied settings, but Superhero 2044 had a fully detailed setting for play. Additionally, it had an innovative combat system that used 3d6 to give a bell curve-ish distribution of possibilities that ensured more skilled combatants would be successful consistently and provided a less “swingy” system than D&D. Superhero 2044’s combat system would go on to influence games like Champions, which is partially a product of Wayne Shaw’s house rules for Superhero 2044. I’ve received permission from Wayne to share his rules and to make a “retroclone” superhero game that incorporates them.

As innovative as Superhero 2044 was, it failed to connect with audiences like later superhero games. This is in large part due to the fact that while the combat system is highly playable, there are no real character creation rules and thus the game is unplayable “rules as written.”Melee & Wizard (1977)

Steve Jackson’s Melee and Wizard rules sets form the foundation of The Fantasy Trip role playing game, a game that could have been the cornerstone of success for Metagaming but which became the foundation of success for Steve Jackson Games. Like Superhero 2044, The Fantasy Trip uses three six-sided dice as the core of its combat system. It’s a detailed and very tactical system that is a ton of fun to play. The skill system expands on the concepts in Traveller and aligns them so they are consistent with the basic combat system.

The Fantasy Trip is one of the first examples of a “core mechanic” game where a single mechanical system is used to determine success and failure in all actions. D&D had different subsystems for different actions, as did Tunnels & Trolls and Superhero 2044. Sales for the game were fairly strong, but a falling out between Steve Jackson and Metagaming resulted in the withering of the line as less experienced designers attempted to pick up the design slack. Steve Jackson went on to design GURPS in the 1980s, but you don’t have to put GURPS under a microscope to see the Melee and Magic roots of the game.Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Monster Manual (1977)

The Monster Manual was the first book published for the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons game and interestingly came out before the Players Handbook or Dungeon Masters Guide. It marked a transition in the hobby from boxed sets and softbound books to hardback books meant to last on the bookshelf. Since the book was released before other AD&D books, players had to use the already existing D&D rules with the book. Since the rules of D&D had been expanded with the Greyhawk, Blackmoor, and Eldritch Wizardry supplements everything a player needed was there, but the player would have to patch them together from a variety of sources and attempt to interpret some of the slight variations from the older game.All the World’s Monsters (1977)

While the whole All the Worlds’ Monsters series is interesting, it is the second volume that is most significant regarding its contents. Not only does it include conversion rules written by Ken St. Andre for Tunnels & Trolls, it also includes Steve Perrin’s “Perrin Conventions.” These conventions, like the Cal Tech and Stanford D&D group house rules, influenced the development of Dungeons & Dragons mechanically. Perrin himself would go on to design a couple of excellent and important role playing games.Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set Holmes Edition (1977)

John Eric Holmes was, in addition to being a professor at USC’s medical school, an influential Dungeon Master in the Southern California gaming community (where the Thief Class was invented). He wrote the Dungeons & Dragons basic set in order to provide an accessible rule set that would appeal to children and to make the very arcane rules of D&D intelligible to the average person. By and large, Holmes did a fantastic job. The rules are easy to read and lack difficult “High Gygaxian” constructions that might require the use of a thesaurus or dictionary to fully comprehend.

The game marks the first time a truly “introductory” game was published, but it wasn’t without its problems. One of those problems is in the presentation of two-handed weapons and daggers. Since all weapons do the same amount of damage in Basic D&D (1d6), every character should only use daggers to fight and should never use a two-handed weapon. This is because daggers attack twice a round and two-handed weapons can only be used every other round of the game. If the weapons had other mechanics that balanced this out, it would be fine (as they do in Chainmail) but they don’t and that’s one reason why this rule set was quickly revised in 1980.Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Players Handbook (1978)

Were you looking for a nice set of combat rules to supplement your new Monster Manual and give you a glimpse into what AD&D’s rules would look like? Sorry, this isn’t the book for you. This book focuses entirely on the creation of player characters and the rules immediately needed by the players. One of the vibes of AD&D was that the Dungeon Master would have information that players did not, and a lot of that information dealt with combat and success and failure of actions. This mystery added to the perceived danger of play, but was relatively unique to D&D as a franchise.

The development of the class and level system here, as well as clarifying how the multi-classing of Elves and other non-human races worked, transformed difficult to understand concepts into logically presented rules. One of the questions answered in the Players Handbook (no apostrophe in the original) is when we use a d12. Every polyhedral set includes them, but they serve almost no function but now we know that we use them with longswords against larger than man-sized opponents. This is one of many reasons the longsword is the best sword.Runequest (1978)

There is a lot to say about Runequest as a game system. Like The Fantasy Trip, it presented a core mechanic system where the success of all kinds of actions were determined by the roll of a “percentile die.” The best thing about this was how intuitive this mechanic is to the average person. You have to think for a moment how difficult it is to roll a 16 or higher on a twenty-sided die, but if you are told you have a 25% chance to succeed then it’s instantly understandable.

Runequest borrowed innovations from Traveller (character background in creation but without the possibility of death) and Superhero 2044 (the inclusion of the richly detailed Glorantha setting in the rulebook), but only in the form of inspiration and not imitation. Perrin’s mechanics are solid and his combat system was based on his experience as a participant in the Bay Area’s Society for Creative Anachronism scene. Given all of the tragedy (tragedy based on cruelty) surrounding this particular chapter of the SCA, it’s probably the best thing to come out of that group…maybe the only good thing. I won’t go into detail here, but searches about Marion Zimmer Bradley and Diana Paxson will give you a picture.

Needless to say, the system has a nice ebb and flow that works well with smaller combats. Where D&D has combat where high level heroes can battle hordes of monsters all by themselves, Runequest focuses on the one on one struggles of epics like Beowulf. Chraacters can, through the learning of magic and runes, exhibit capabilities that echo the legendary heroes of Greek Myths even as the system retains an individual rather than group focus. The famous cover, and a lot of the interior art, was drawn by Steve Perrin’s wife Louise.Arduin (1978)

Arduin was huge in the Bay Area when I was a kid. If you were playing AD&D, and I was playing a lot of 2nd Edition, then you were playing a version of the game with a touch of Arduin influence. Where Gygax attempted to push back against D&D being heavily influenced by Tolkien, it was clear that D&D fantasy as played by most was often Tolkien fantasy. This was true even with science fantasy modules like Expedition to the Barrier Peaks or references to Edgar Rice Burroughs all throughout D&D books.

That was not the case with Arduin. Where the races focused on in the D&D core books were Dwarves, Elves, and Halflings (Hobbits in early OD&D), Arduin expanded the options with Phraints (insect people) and a ton of optional classes spread throughout The Arduin Grimoire (Arduin Grimoire volume 1), Welcome to Skull Tower (Arduin Grimoire volume 2), and The Runes of Doom (Arduin Grimoire volume 3).

These books are pure DIY content from David Hargrave, who was praised throughout the Bay Area as one of the best DMs in the region. Hargrave was a fount of ideas, but he had no concept of game balance or mechanical design. This is one of the reasons he never caught on as a designer with Chaosium. He did some work in All the Worlds’ Monsters, and was hired to do more work, but wasn’t able to deliver product reliably. Writing and balancing mechanics is hard, even when you are as creative as Hargrave was. These books mark the end stage of Little Brown Book design where ideas could be contradictory and opaque, so long as they inspired play. D&D transitioned from OD&D to AD&D (and Basic) and became cohesive while remaining creative. Arduin is just idea after idea without concern for consistency or balance and it’s beautiful. Gygax may have created a magic item, the Vacuous Grimoire, because of his ire at this game but I love it and its importance as a DIY small press product is undeniable. This is raw OSR.Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Dungeon Masters Guide (1979)

At last we can reveal the rules to the players. At last, we can have…an edition. With the publication of the Dungeon Masters Guide in 1979, Advanced Dungeons & Dragons was finally fully revealed to the gaming community. That’s not what makes puts the DMG on this list though. Consistency and cohesiveness was evident in the Players Handbook. What the Dungeon Masters Guide offers is fantastic advice for how to run a game, advice applicable to any system, a good introduction to probabilities, details on how to create a world, AND more conversion rules.

While All the Worlds’ Monsters was the first book I can think of that included conversion rules for different game systems, Gygax including them in here opened the door to what was for a period of time a regular practice. In fact, it is something I deeply miss. So many modern games are based on the same mechanical structures, and when they aren’t they don’t include conversion rules. There was a sense of coopetition, rather than pure competition, in that concept in a way that combined creativity and collabortation. There’s some great coopetition today, with open licenses etc., but it seems like people get trapped in single mechanical representations today. Either you play D&D and games based on D&D or you play other games, but most modern players don’t know as many different systems and I blame the lack of conversion rules for that.Villains & Vigilantes (1979)

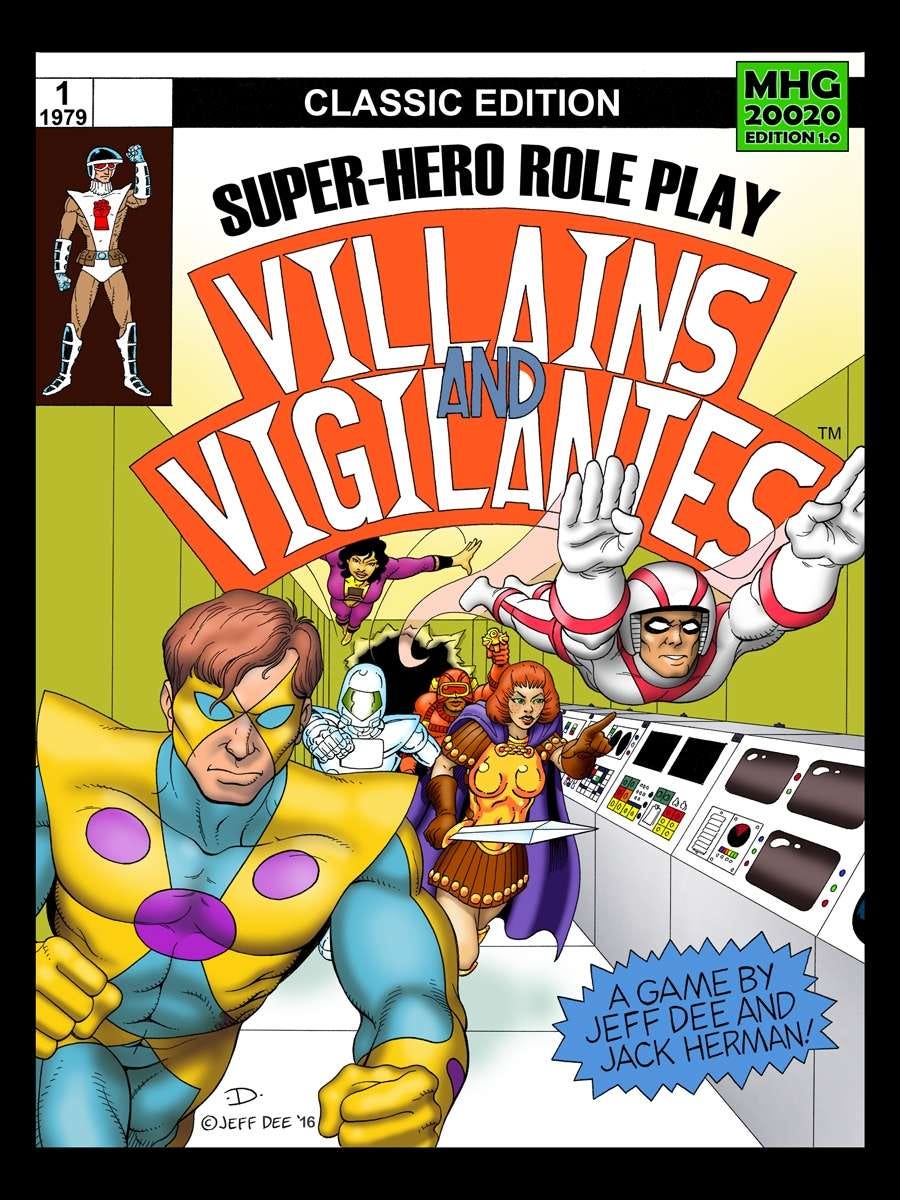

Superhero 2044 was the first superhero role playing game, but Villains & Vigilantes was the first fully playable superhero role playing game. It’s also a game that holds a special place in my heart. I didn’t play 1st edition V&V when I was a kid, most of my game play was with the 2nd edition, but the first edition is very fun to read. The game recommends that the heroes you create be alter egos of the actual players, where the Game Master assesses each player’s real life statistics, but most people never played that way.

The first edition uses a level system and a relatively complex percentile system for combat. This complex system, which requires the adding of a number of factors for a final to hit number, was replaced with a simplified d20 based system. At the time V&V was published Jack Dee and Jeff herman were the youngest game designers to have a published game and this book marks the solidification of fully random character creation. Where many super hero games let you build your character, V&V has you randomly roll your powers. In many ways, this fits the genre a little better than building in my opinion. Either way, it’s a ton of fun.

Great list. Haven't played any of them, but maybe I will see if I can find copies of them. So I can check out the past of RPG games.

I had and played more than half of these, but I'd swap 'em all for Empire of the Petal Throne.