St. Patrick's Day Movies

Did You Party or Engage in a Movie Marathon Like I Did?

Holidays are a Time for Films

It will likely come as no surprise to anyone who has read one or more of the Weekly Geekly Rundowns I publish each (usually) Friday, but I am a huge fan of cinema. I’ve long lost count of how many films I own in various formats and I subscribe to enough streaming services, ranging from the potentially pretentious Criterion Channel to the cult focused Shout! TV, that I don’t have enough time to watch content on every one of them every month.

This does mean that I’m often paying for services I haven’t used, but it’s worth it to me because I never know what I’ll be in the mood to watch. Rather, I never what what I’ll be in the mood to watch unless it’s a holiday. At my house, the Halloween season means a nightly horror film screening finished off with a viewing of The Nightmare Before Christmas. Once that benchmark has been passed, it’s a long stream of Hallmark and Classic Christmas movies for the next two months. Sure, we might watch something that isn’t Christmas themed in November and December, but we will have at least one Hallmark or Christmas film on every day during that season.

Of course, we watch 1776, The Scarlet Coat, and The Patriot (to name a few) as we approach July 4th and my viewing thematic viewing habits sometimes extend beyond holidays as I try to watch the “Battle of the Bulge” episodes of Band of Brothers in December even as I watch the D-Day one in June. All of which is to say, when I don’t know what my exact cinematic mood is, I default to the season.

This past weekend, my wife and I did something we had never done before. We added St. Patrick’s Day to our list of mandatory movie merrymaking marathons. One the one had it make a certain kind of sense. My wife’s grandfather’s name was Cosgrove and his family migrated over from Ireland, so there’s Eire in the family. On the other hand, it’s a bit strange. Just as America’s celebration of St. Patrick’s Day is a little strange. The manner and means that America celebrates St. Patrick’s Day says more about American’s love of parties than it does about any particular cultural attachment, so too does the upcoming annual American celebration of Mexico’s victory over the Second French Empire at the Battle of Puebla in 1862 (aka Cinco de Mayo).

Just as America loves to find an excuse for binge drinking, so too do I love to find an excuse for a movie marathon (or an rpg adventure). The fact that the holiday also lines up with Spring Break makes it ideal for these kinds of activities. Thankfully, there are a lot of excellent movies by Irish directors or about Ireland or Irish Americans. One does not have to rely solely on the Leprechaun series when planning screenings on St. Paddy’s.

This Year’s List and Brief Comments

We had a very limited movie marathon this year because we already had plans to go to Grandma’s house for Corned Beef, Cabbage, and Soda Bread, and it also was the first day in our once in every eight years tradition of “Eight Days of Birthday” for our twin daughters. So this year’s “marathon” was limited to three movies. One is an all-time classic, one is a charming but mid-tier romantic comedy, and the last is a film that will become a classic.

I’ll provide the list here with micro-reviews, but I plan on giving each a full YouTube and written review at some point in the future. They all deserve it, even the mid-tier romcom.

The Quiet Man (1953)

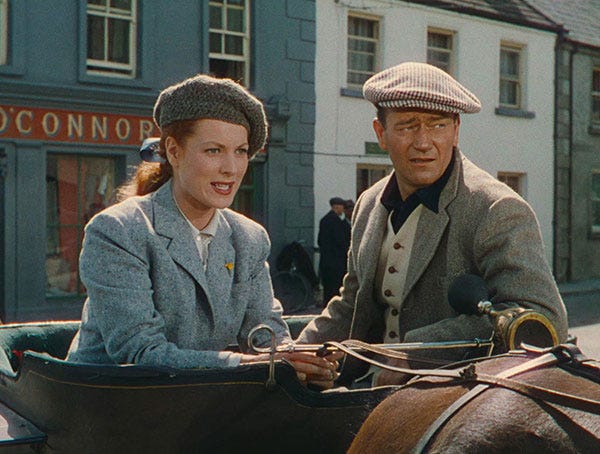

John Ford’s classic film The Quiet Man (1952) is one of the all-time great films of classic Hollywood. Yes, it has moments that make modern audiences wince, both from a film technique and from a societal change perspective, but the overarching tale and craft are wonderful. John Wayne’s performance in the film is more subtle than he is given credit for as John Ford pulls out some wonderful moments of “nostalgic glance” from him and Maureen O’Hara is as much a force of nature as her character.

There’s more going on under the surface in the motivations and emotions of the characters than some reviewers might notice, O’Hara’s character is demanding respect for the things she owns. The Ireland of the film is deeply patriarchal, but Mary Kate Danaher is an interesting character. She is simultaneously respectful of tradition, while pushing for an autonomy from it that marrying the American who moved there will allow. Breaking that down would take chapters, but one example of this is when Sean Thornton (John Wayne) gives her the carriage and tells her it is hers. Mary Kate’s reaction tells you a lot about how important her ability to own something is, add to this that it is a means of transportation that is being given to her and you’ve got some powerful symbolism there.

It would be a mistake to argue that John Ford was a modern, or even a 50s, progressive, but it would also be a mistake to overlook his critiques of staid traditions and bigotries.

The Quiet Man was nominated for 7 Oscars and won 2. It won for Best Cinematography (color) and Best Director. The cinematography is stunning, but it is also reflective of an era of transition. Matte paintings are almost invisible in black and white films, or at least less disruptive to suspension of disbelief, and The Quiet Man has a couple too many Matte backed shots for my tastes, but the film was made when their frequent use was more common. Modern films still use them, and their digital equivalent, but they are less obvious in their application today. High Noon was also released in 1952 and nominated for a number of Oscars, including Best Cinematography (Black and White) which it very deservedly won, but neither it nor The Quiet Man was Best Picture. That honor went to a film that gets far less talk today, The Greatest Show on Earth. There is spectacle in Greatest Show, but I don’t think it has the same long lasting emotional power as the High Noon, The Quiet Man, Moulin Rouge, or Ivanhoe. My vote would have been for High Noon, but The Quiet Man is the best St. Patrick’s Day “themed” of the bunch.

Irish Wish

Lindsay Lohan is an interesting actress. She’s a child actor who is often under appreciated for her intelligence and charm. While I don’t know how accurate the stories are, she is also reported to speak several languages. Given how often the stories are repeated, I’m willing to give her the benefit of the doubt. Especially given the fact that she showed some business savvy when she, like Adam Sandler before her, leveraged her talent into a multi-movie deal with Netflix.

In the case of Adam Sandler, his deal has not only allowed him to use production budgets to take amazing vacations with his friends, it has also made him the highest paid actor in Hollywood. In Lindsay’s case, she has demonstrated that she is a big streaming draw for romantic comedies, a fact that has shown that audiences are hungry for charming love stories or at least love stories with charming people.

That’s what you get with Irish Wish. It’s a very by the book romantic comedy, with some moments that don’t quite hit their mark, but Lindsay Lohan and Ed Speleers are so charming in it that it works. The basic premise is that Lindsay Lohan’s character makes a wish to St. Brigid, a wish that will give her “what she needs” more than what she wants. This results in a kind of Family Man exploration where the protagonist learns what she really wants and who really loves whom. There’s a little magic in the use of self-realization here that might get overlooked and there are some wonderful scenic shots. The set design doesn’t quite work sometimes (like when they “dress” the chapel for the wedding), and while I know it isn’t the case I kind of wondered if the costumer hated Lindsay. She’s constantly put in terrible plaid outfits, but maybe they were trying to signal “Hey she’s in Ireland!”

Anyway, while not a deep film, it was a pleasant film to watch with someone I love.

Belfast

Kenneth Branagh has long been among my favorite directors. Whether it’s his Shakespeare adaptations, his underrated Marvel and Jack Ryan films, or his murder mystery work (from Dead Again to A Haunting in Venice), I find him to be consistently excellent. He tends to find aspects of material that might have been overlooked by others in the past. His Henry V added a real sense of verisimilitude to the History and his Hamlet reminded audiences that Fortinbras was the model Hamlet should have followed (and that the real world Amleth did). It’s often overlooked that Fortinbras is invading at the end of the play and that Hamlet and others are focused so narrowly on the intrigue within that they overlook threats without.

I didn’t know what to expect when I watched Belfast. I knew that it was a coming of age story that took place during The Troubles in Ireland’s history. Something akin to an Irish version of John Boorman’s Hope and Glory. But where Boorman’s film showed how childhood was still childhood even during “The Blitz,” Branagh’s would show that same phenomenon within The Troubles. That’s certainly there and that’s what many critics responded to when they saw it, and those that did often found the film to not be “brave” enough.

I saw something different. I saw a film about being a parent, that used The Troubles as a metaphor for the fears that every parent has and I saw it as an extremely brave and personal film to make. I often say that a parent alternates between two emotional states. Their life alternates between moments of complete abject fear during a moment of crisis or threat and a constant dull humming of dread that becomes the background noise of life. Something can always go wrong and harm your children and the thought of that is always there. It is background noise. No matter how happy the moment, the dread is there. It’s not overpowering. It isn’t crippling. It just is. It is the new rhythm of life.

Belfast captured that perfectly. Where other critiques might have wanted more shocking moments of violence and death, and saw the lack of them as a failure to push boundaries, I would have seen any such moment as cheap and forced. Take a look at the picture below. It’s a picture that I think perfectly captures the entire narrative of Belfast.

Buddy (Jude Hill who is excellent) is watching his parents discuss the future, in this case discussing back taxes. In other scenes Buddy sees his mom and dad talk about moving from Ireland due to physical danger, but the family’s back taxes are a major point in the film. They are real. They are as much a threat as the violence around them. They are oppressing the family as much as the local Protestant mobsters.

Adults watching the film know this moment is real. It’s real in a way that critics of how “safe” this film was don’t seem to realize. It’s not safe to have a major plot point be conversations about taxes and debt, in a backdrop of real violence. It’s brave to choose to ignore the easy out of showing violence while focusing on the mundane. It would have been easy to wallow in the horrors of The Troubles, but it would have been cheap. The film uses the knowledge that it could venture into Peckinpah-esque excesses of violence as a tool to manipulate the viewer. I constantly wondered when Buddy’s father, or mother, or brother, or girlfriend, was going to get killed. I worried. I felt the constant hum of dread. I felt the tension of being a parent.

Branagh’s film connected with me in a way that few films ever have. It showed love. Real love between the parents. Real love for the children. It showed parenting, with sometimes bad/foolish choices we make. It was magical.