Zones of Control: A History of Miniatures Combat in D&D

No. Attacks of Opportunity are not a new concept in D&D.

This is a very long and pedantic post about the history of miniatures in D&D and the concept of Zones of Control.

Enter at your own peril.

Why am I Revisiting Miniature Combat and Zones of Control in D&D?

There are a number of arguments about Dungeons & Dragons that pop up from time to time about the way the game is and/or has been played and when certain innovations happened. Some of these are new(ish) arguments like the BroSR discussions about 1:1 time, while others are evergreen. There is one evergreen statement that get’s my goat a bit and that’s the argument that 4th edition changed D&D from a theater of the mind style role playing game into a tactical miniatures game.

This is one of the many subset of arguments people will make regarding how they believe “4th edition isn’t really D&D.” The two most common arguments along this line are that 4th Edition “doesn’t have rules for role playing” or that it is a miniatures combat game and not a role playing game. Those making the first argument typically mean 4th Edition doesn’t have a skill system, which is its own conversation that I addressed in the past. I disagree with that group, but they don’t get my goat the way the “4e is just a miniatures game” people do. I think that it is evidence that they haven’t taken the time to read earlier versions of D&D carefully and have instead been playing the game using the common cultural rules rather than the written ones.

I Liked D&D More Before it Became GURPS

“Almost all old school dungeon delving is an off the cuff Player VS DM negotiation made in the moment.” — Jim Zub

Why?

Because every edition of Dungeons & Dragons is a miniatures based tactical role playing game.

This doesn't mean that those playing without miniatures were "playing the game wrong." I've played in at least one campaign in every edition of D&D and there are plenty of rules my gaming groups have either ignored or added to make our own experience more fun. Here are just a few ways my groups have modified game play:

None of the 1st Edition AD&D campaigns I've played in has ever used the Weapon Speed Factors or the Modifications for Armor Class.

I've played in 1st Edition games that used "Spell Points" for spell casters.

As a Game Master, I've disallowed non-Lawful Good Paladins in 3.x, 4e, and 5e. Paladins are Lawful Good and that’s final.

I had a DM who used Arduin's Damage System in his AD&D Campaign.

I've never used the initiative system from Eldritch Wizardry.

I give every race a second wind as a minor action (Dwarves get it as a free action) to speed up play.

One campaign I played in had us set our miniatures on the play mat in "Marching Order." No matter the shape of the room our characters were attacked based on that formation in Bard's Tale-esque fashion. We could have been in the center of a room 100' x 100' and all of the melee attacks would have been targeted at either the front row or the back row without anyone attacking our Magic Users in the middle.

Every one of the games I played with these groups was fun and thus none of these groups was playing "incorrectly." None of these groups played games to the rules as written either. No one - with the exception of organized play - have any moral responsibility play only the rules as written, though I would argue you should at least read the rules to understand them and try them out for at minimum one session.

Role playing games are written to be adapted to play for your local gaming group. There are two key elements that allow for this without "breaking" the game. First, there are no winners and losers in D&D. The only way to win is to have fun and changing the rules for your local group is one way to create fun. Some changes are fun for a short time before they create more boredom than fun - in general - so there is room for advice regarding power scaling and Monte Haul campaigns, but the aim is to maximize fun. Second, most role playing games - excepting a couple of innovative Indie games - have a Game Master who moderates the game and who has absolute authority in rules interpretation in the local gaming group. So long as the Game Master is fair and focuses on keeping the game entertaining for the players in his or her group, then what rules are included or left out don't matter much.

As I mentioned above I get annoyed when someone tells me in person, or in Twitter/Facebook discussions, about how 4th edition of Dungeons & Dragons isn’t D&D because it "requires the use of miniatures" or "feels more like a board/tactical video game" than it does a role playing game. These comments always strike me as odd. Not because the way people have played D&D has required miniatures and battle maps. There have always been campaigns that have elected to neglect the granular miniatures rules of D&D and highlight the abstract nature of what the White Box called the "alternative combat system." What strikes me as odd is that these comments seem to have as an underlying assumption that the Rules as Written of D&D didn't assume the use of miniatures in every edition -- including the 4th. There are some peculiarities of the 4th edition that make it more difficult to abstract away from -- many of which also exist in 3.x/Pathfinder -- but the game has always been rooted in miniatures as its default method of play.

I imagine I could try to defend my D&D's "miniatures as default" position by taking quotes from various editions which discuss how the game is a game of miniatures combat, like the fact that the original rules call themselves "Rules for Fantastic Medieval Wargames Campaigns Playable with Paper and Pencil and Miniature Figures." But I think a line of argument like that one would become boring and could easily turn into a "just because it says miniatures doesn't mean they actually used miniatures" argument. And because of the varied ways that people have actually played the game throughout the years, no one would be right and it would just be a bizarre pedantic discussion. I'm not talking about a "right way" or a "proper way" to play D&D, I'm just talking about what the default setting of each edition was and how it was reflected in the rules -- in this case one particular rule. For the sake of full disclosure, I will readily admit that half the campaigns I played in ignored many of the miniatures as default rules. All of the games I have played in have ignored that bizarre "weapons vs. armor" chart in the AD&D Player's Handbook.

Zones of Control

One of the key mechanics that demonstrates the miniatures as default setting is the fact that every edition of D&D has had some form of ZoC mechanic. That's right, every edition. To understand this statement, it would be helpful if I shared what exactly a ZoC mechanic is. I have always found Jon Freeman's definition in The Complete Book of Wargames (1980) to be very useful in this regard, as ZoC rules are somewhat arcane and difficult to understand for all but the most hard core hex and chit wargamer. Jon defines a Zone of Control in the following way:

Zone of Control (ZOC) -- A unit's "sphere of influence," usually the hex it is in and the six adjacent hexes that affect opposing units. Effects vary greatly but usually involve combat, movement, and/or supply.

To rephrase, a Zone of Control is an area around a unit (character or combatant) in which that unit can affect the combat ability, movement, and/or supply of other units.

In OD&D, the ZoC rules varied depending on whether you were using the Chainmail rules system or the "alternative combat system" provided in the Men & Magic booklet.

Zones of Control in Chainmail and Chainmail Inspired OD&D

If you use Chainmail as your D&D combat system, there are two core ZoC rules that make it a “hard” Zone of Control system. First, if units were engaged in melee they remained in direct contact with one another until one unit was destroyed, broke, retreated, or was forced back in "good order" based on a resolution of unit morale. At no point could any unit withdraw willingly from melee combat excluding a morale result. Once combatants were engaged in melee, they were stuck in the other unit's Zone of Control. One thing that might be shocking to modern gamers is that Melee Range in Chainmail is 3 inches and that figures within that distance change choose to engage in melee combat.

As mentioned above, the only way out of melee is the forced movement caused by a result of a morale check and for many units morale is checked before, as well as after, combat has been engaged.

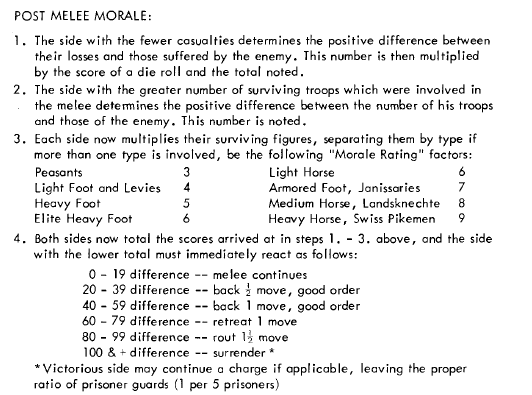

The morale system in Chainmail is relatively complex and combines a number of factors: the roll of a dice, the difference in casualties, the difference in remaining unit size, and the quality of units. The process then results in either the melee continuing, one unit being forced out of combat in “good order,” one unit being forced out of combat in disorder (either retreat or rout), or surrendering.

The section on man to man combat it states that excepting modifications, all the earlier rule apply including the rules for morale.

Given that differences in casualties and remaining troops play such a big role in the morale system for mass battles, one might wonder how exactly morale might work at the smaller scale of man to man combat, particularly when involving “high” level characters. Remember, we are talking OD&D using Chainmail rules here and while the designers might never have used that system, it is one possible system presented in the rules. We are given one hint in the normal post-melee morale chart regarding how to treat D&D characters. It is possible that the D&D characters might use multipliers of the troop type that most closely represents their equipment, class, and level. For example a fighter or cleric in Chainmail might fight as “Heavy Foot” and one in Platemail might fight as “Armored Foot.”

This logic is consistent with the description of Wizards, who are said to fight as “two Armored Foot, or two Medium Horse if mounted.” This would give Wizards a base of 14 (7 * 2) or 16 (8 * 2) morale which could then be used in the process above.

Fighters, Clerics, and higher level Magic Users who count as “Heroes” or “Super Heroes” according to the experience chart would use a different morale number. For Heroes it would be 20 and for Super Heroes it’s 40. This is consistent with treating a 1st level fighter as Heavy Foot (morale rating 5) since a Hero is the the equivalent of 4 “men” and the Super Hero is the equivalent of 8. Needless to say, because of the rarity of any morale result between small numbers of combatants resulting in a 20 point spread this means that Zones of Control in man to man combat are very sticky. At least this is the case for low level combatants.

The second ZoC rule in Chainmail deals with "Pass through Fire" during the movement phase. In effect, missile troops have a ZoC that affects the movement of all units passing through their line of sight who are within their firing range. Chainmail has two ZoC rules which require the use of miniatures to properly implement.

There are some additional nuances to these rules, but this post isn't a detailed discussion of Chainmail. I'm just pointing out its ZoC mechanics with broad strokes.

Zones of Control in OD&D’s Alternative Combat System

The "alternative combat system" presented in the Men & Magic booklet is the system that eventually evolved into the one used in all later editions of D&D. It is the core d20 mechanic of the game. Chainmail style combat, or at least Tony Bath style combat which influenced Chainmail, can still be seen in games like Warhammer and other dice pool combat systems. As an aside, I wouldn't even be able to understand Chainmail if I weren't a Warhammer gamer. In the Men & Magic book, the alternative combat system is presented solely in the form of two charts which provide the number needed in order to hit an opponent based on the armor they are wearing. These charts are on pages 19 and 20 of the booklet. There is no discussion in that booklet of how to apply the system or how movement works. Movement rates are provided in inches corresponding to the movement system used in Chainmail, that of inches on a table surface.

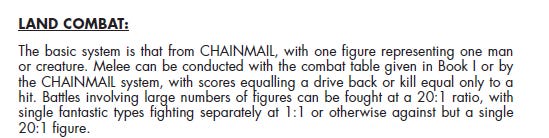

The Underworld & Wilderness Adventures booklet does have some clarifications and extensions to the alternative combat system, clarifications which imply that Chainmail’s hard ZoC system still applies. On page 25 of Underworld & Wilderness Adventures, it states "the basic system is that of Chainmail... Melee can be conducted with the combat table given in Volume I or by the Chainmail system, with scores equaling a drive back or kill equal only to a hit."

This is expanded upon on page 28 where the size of an individual figure's ZoC for melee purposes is revealed, "When opponents are within the range indicated for melee (3") then combat takes place. Of course if one opponent is in a position where the other cannot strike, then only one will be able to attack, just as in combat on land." In other words, figures enter into melee with figures within 3" of them -- at least for Air to Ground attacks. Ground to Ground attacks might still require figures to be adjacent.

Regardless, there is no articulation of a means to disengage from melee in the White Box rules if one views the rules system as an extension of Chainmail’s system than those rules do apply. Additionally, the Greyhawk Supplement adds an "attacking from flank/rear" chart that is clearly intended for miniatures use. Eldritch Wizardry breaks the inches of movement down to how much a character may move within a specific "segment" of a round, once more implying miniature use.

While there are no voluntary disengagement rules in OD&D or Attacks of Opportunity, in either Chainmail or the Alternative Combat System, one can see the foundation for Attacks of Opportunity in the “move in good order” and retreat/rout results. If a unit loses a morale check and has to move away in good order, the opponent may follow up and attack again but that attack takes place in normal combat where both the attacker and defender get a strike. When a retreat/rout result occurs, the attacker may follow up and re-engage, but the defender gets no counter attack. It’s not exactly the same, but it creates similar effects.

Given that melee range is 3 inches (read 30 feet), this makes the Zone of Control in dungeon settings extremely hard/sticky. Imagine you are in a typical dungeon room for an early D&D module, in this case depicted by map B from Dungeon Geomorphs below, most of the rooms are much smaller than 30’ x 30’ (aka 3” x 3” assuming 10 foot squares). One positive tactical effect of the smaller rooms is that if you have friends outside a doorway, you can have them use their action to close the door if you are forced to retreat in good order. Another interesting effect is that essentially everyone within an averaged sized room is within melee range making it relatively easy to play “theatre of the mind” while still adhering to rigid Zones of Control.

Formal Introduction of the Attack of Opportunity to D&D

The Swords & Spells miniatures rules, which were written as a replacement for Chainmail, finally provide some firm rules for disengaging from melee. These rules also strengthen the link to miniature use and reinforce earlier assumptions:

“special figures may be withdrawn from melee at any time desired, but opponent figures are allowed an additional round of attack wherein the withdrawing figure does not strike back.

In this we see the origins of the "attack of opportunity" system many think originated with 3rd edition D&D. We also see a strengthening of the ZoC of meleeing units. Melees may, post Swords & Spells, not be disengaged from except by special units who must be willing to endure a free strike. In this way, special units (aka PCs) lock in enemy troops while being able to disengage if they are able to withstand a free strike.

Attacks of Opportunity in Holmes Basic D&D

By the time we get to Basic D&D, the free strike rule from Swords & Spells becomes the standard D&D rule. We also see a significant change in both the time scale of the average combat round and how far a character can move during a round of combat. In Original D&D/Chainmail, a figure can move between 6” and 12” in a combat round (60 to 120 feet) depending on the armor they are wearing. The combat round in OD&D/Chainmail also represents 1 minute of time (page 8 of Chainmail and page 8 of OD&D Book III: The Underworld & Wilderness Adventures).

Combat may be “fast and furious” in OD&D, but movement in Holmes Basic is slow and ponderous. This is because Holmes changes the combat round from 1 minute to 10 seconds. In doing so, he reduces movement speeds correspondingly to only 20 feet when unarmored or 10 feet if armored.

If Holmes retained the 30’ melee Zone of Control from OD&D and Chainmail, this would make it almost impossible to move out of combat, but Holmes shrinks the ZoC down to 10 feet. Given my comment above about dungeon room sizes and how they interact with the Zone of Control, the reduction of the size of the ZoC makes sense. The reduction in movement speeds makes less sense, but there are a lot of quirks in Holmes Basic D&D. Let’s just say that everyone should be wielding daggers in melee and no one should ever use two handed weapons or crossbows. With regards to the D&D has always been a miniatures game conversation, I would ask you too look at how Dr. Holmes uses the term “figure” to describe player characters.

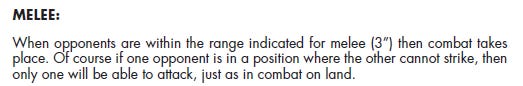

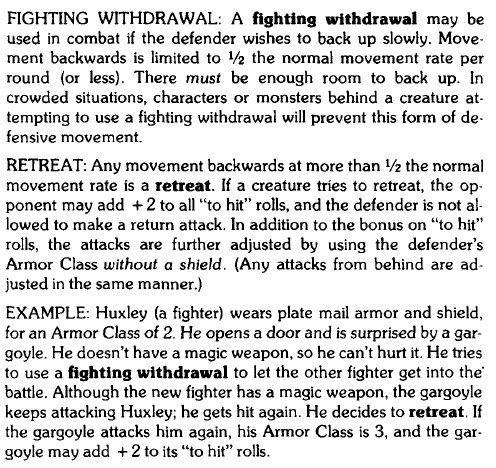

The rules for willingly disengaging from melee provided by Dr. Holmes are particularly dangerous for the character leaving combat. "A character may withdraw from combat if there is space beside or behind him to withdraw into. His opponent gets a free swing at him as he does so with an attacker bonus of +2 on the die roll, and shields do not count as protection when withdrawing." The Holmes Basic Set has similar ZoC rules as Original D&D (as modified by Swords & Spells) with a bonus added to the attacker, which makes the Holmes Basic ZoC even more deadly. Once locked into melee, the player really has to weigh his/her options because any withdrawal leads to an Attack of Opportunity.

Attacks of Opportunity in Moldvay/Cook Basic D&D

The Moldvay/Cook Basic Set makes even more changes to the simple combat system of D&D. Moldvay and Cook retain the 10 second combat round, but they add more granularity to the movement rules. The slowest combatants still move only 10’ per round but lighter armored or unarmored combatants move significantly faster making it possible for Thieves and Magic Users to get out of melee range.

In addition to allowing certain combatants to move faster in an average melee round, Moldvay/Cook shift away from the standard 10’ “square” as the basis for movement and use 5’ as melee combat range. This allows for even more tactical movement within a dungeon space and shows a reduction of the Zone of Control from 30 feet (3”) to 5 feet (1/2” or 1” on tactical map).

Keeping with the added tactical options of a further reduction in scale, Moldvay and Cook give those wanting to withdraw a bit more flexibility with its "defensive movement" options. One of those options is identical to the Holmes/S&S option. The other option allows for a "fighting withdrawal" where the combatant can only move 1/2 their movement rate, but don't provoke an attack in doing so. Moldvay and Cook stress the utility of miniatures, "If miniatures are not being used, the DM should draw on a piece of paper or use something (dice work nicely) to represent the characters in place of miniature figures," so it isn't surprising that they adds another tactical layer to how ZoCs work in D&D. By his edition, they restrict movement somewhat but leaving a Zone of Control doesn't always provoke an attack.

It should be noted that the rules of combat up to the Moldvay Basic set are so arcane in their presentation, that most people had to make up how to play the game. It is also true that it is pretty easy to ignore the ZoC, or to just assume melee contact for melee combatants and ignore "position" bonuses/penalties, and rely strictly on the d20 rolls as the entire system. In fact, this is how my first group played.

We were too young to be able to afford minis, so we just used common sense regarding who was in melee -- rarely the magic user -- and alternated d20 rules. There was very little tactical maneuvering in our games, but a great deal of fun. It is memories like ours that I think lead people to remember D&D as an abstract game rather than a minis game. My memories of abstract play are correct, but the rules had a default minis use setting that had "opportunity attacks" akin to 3.x.

Attacks of Opportunity and Zones of Control in AD&D

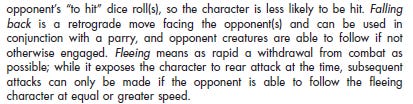

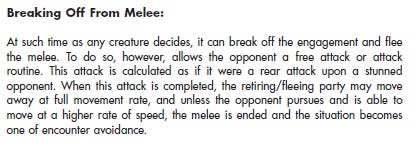

The rules for "free attack" Zones of Control change again in the AD&D Players Handbook (sic). The AD&D rulebooks were an attempt to make D&D rule more specific and consistent, but they also compartmentalized the rules in some interesting ways. While the main combat rules are in the Dungeon Masters Guide (sic) starting on page 61, the Players Handbook (sic) includes rules for parrying, falling back, and fleeing (page 104). AD&D shifts away from the quick combat rounds of Basic and returns us to 1 minute long combat rounds.

In the case of exiting a Zone of Control in AD&D, falling back is the preferable action, but doesn't truly prevent an opponent from attacking you unless you have a higher movement than they do. The opponent may still attack you, but only if they have sufficient movement to follow and if you are parrying they suffer a penalty. Fleeing combat is similar to earlier withdrawals. This is a much “looser” ZoC than in OD&D or Basic.

It should be noted that page 70 of the AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide (sic) does have the older method of opportunity attacks. This is one of those cases where when older players say “just play AD&D using the rules as written” where the response should be “which rule?” The common heuristic is that rules written later supersede prior rules, in which case you use the Dungeon Masters Guide, however there are two distinct Zone of Control systems at play here and one is far “softer” than the other. Given that page 66 of the Dungeon Masters Guide says that the “Close to Striking Range” action is “typically taken when the opponent is over 1” distant” we can surmise that the baseline melee range in AD&D is 10 feet. This might be modified based on weapon lengths described in the Players Handbook, but no specific conversation of “reach” is given with regards to Zones of Control.

The Dungeon Masters Guide also states the following, "if characters or similar intelligent creatures are able to single out an opponent or opponents, then the concerned figures will remain locked in melee until one side is dead or opts to attempt to break out of combat." There are numerous references to figures, movement rates in inches, illustrations to determine flank/rear attacks. The assumption here is on the use of figures -- even though the rules are easily abstracted. One thing I find interesting is that AD&D also includes two different grid based systems for combat, which obviously suggests the use of battle maps. They provide facing rules for both hex and square grids.

Zones of Control and Attacks of Opportunity in 2nd Edition AD&D

As with AD&D, the 2nd edition of AD&D uses one minute long combat rounds during which combat is highly abstracted. Page 57 of the Dungeon Master’s Guide (page 82 in the Revised Dungeon Master’s Guide) states that “as a guideline, the AD&D rules assume that two fighters using swords can work side-by-side in a 10-foot-wide area. The same space would be filled by one fighter using a two-handed sword.” This suggests that “close” melee range would be 5 feet, but that for weapons with reach it might be a larger area.

This leaves the radius of a Zone of Control up to the DM’s judgement, based on the character’s choice of weapon. This determination is important because 2nd edition AD&D has withdrawal rules that are very similar to those of AD&D that are provided on page 59 of the Dungeon Master’s Guide and on pages 81 to 84 of the Revised Dungeon Master’s Guide.

The 2nd edition of AD&D has facing rules that are similar to those of AD&D, but more abstracted to allow for some semi theatre of the mind style play. Where AD&D provided hex and square grids to demonstrate facing and where opponents attacked from, 2nd edition provides illustrations that could be adapted into templates in a more abstract game experience.

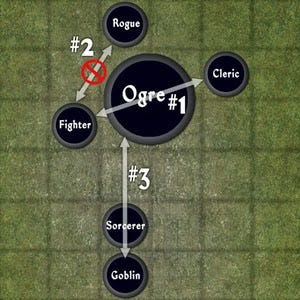

Zones of Control and Attacks of Opportunity in 3rd Edition D&D

In editions 3.0 and 3.5 the rules began to make it more difficult to abstract combat in the way earlier editions could be. While all the editions assumed miniatures use as a default setting, earlier editions were also easy to abstract. Third edition and 3.5 marked a significant change in this regard. They can be played in theatre of the mind, but rules for effects like "threatening" and "flanking" throw a significant monkey wrench into the abstraction gears gears. They tried to present these themes "abstractly" in the 3.0 PHB by illustrating how a figure threatens the space around it while not using a grid in the illustration. Given how central rules for threatening are in 3.x rule sets, and how they are an example of rigid Zone of Control mechanics, this edition is best played with miniatures.

As you can see below, they quickly gave up on attempts to have threatened area and flanking be abstracted when they published the 3.5 rulebook. Gone is the illustration using tokens and in is the formal inclusion of squares and the new miniatures line in the diagrams. Once they produced that rule book, not only was the default assumption use of minis but the mechanics basically required them. To not use minis was to abandon the benefits of a number of feats and tactical choices, or to limit those choices by subjecting them to "common sense, consensus, or fiat."

I attempted to used common sense and verbal descriptions early in my 3.x experiences, but this quickly proved inadequate to my players who had years of experience playing Champions and Battletech. They wanted clear display of their tactical choices, and who could blame them. The 3.5 rule books certainly didn't and it was off to the game store to buy Steve Jackson’s Cardboard Heroes for me. The rules for Attacks of Opportunity were a direct descendant of the withdrawal rules in Moldvay/Cook Basic.

One major clarification to the Zone of Control system that was added in edition 3.x was the formalization of “reach” as a component. Most weapons could only attack foes in adjacent squares, but some weapons have the “reach” quality which allows you to attach opponents 10 feet away. This extends the effective Zone of Control for those weapons from 5 feet to 10 feet, though in the case of a Longspear the ZoC does not include adjacent squares.

While the Zone of Control in 3.x is closely related to the withdrawal rules for Moldvay/Cook Basic, there is one major change that makes the ZoC less “rigid.” In Basic, you get a free attack against any foe who moves away from you without using the withdrawal maneuver. In 3.x, you can only make one such attack unless you have the Combat Reflexes feat. In that case, you can make one additional Attack of Opportunity per +1 bonus from your Dexterity.

Even a game that was “reacting against 4th edition,” but which was really primarily reacting against the removal of the OGL, like Pathfinder had extremely tactical and miniatures based combat assumptions.

Zones of Control and Attacks of Opportunity in 4th Edition D&D

Fourth edition merely continued the trend of all earlier editions, with the use of the "threatening" ZoC while also making it slightly more abstract. What it added were layers of how to create additional opportunities for the ZoC to have effects. It also added ZoCs to certain spells with the full articulation of ZoC spells for "controllers." These are all things that were in the rules from the beginning of the game.

While the flanking rules were similar to 3.x, one of the effects that flanking had was to grant “combat advantage” which allowed for (among other things) thieves to use their sneak attack.

One of the interesting things about 4th Edition is that you could gain Combat Advantage merely by taking the right feats. For example, the level one Thief Ability First Strike gave you combat advantage at the start of an encounter against any creatures that have not acted yet, and thus allowed for more abstract applications of sneak attack than 3.x. In many ways, 4th edition was less dependent on the map than 3.x for the activation of some effect. For others, like auras etc., it was almost as reliant.

Each of these editions demonstrates the influence of tactical wargames on the combat systems of each edition. It should also be noted that each edition of the game adds new layers of complexity regarding what affects whether you are in a Zone of Control and whether you are flanking an opponent. Pathfinder, 3rd Edition, 3.x, and 4th edition all have creatures with reach that expands their Zones of Control and each of those games has specific rules regarding how conditions influence your ability to flank other combatants. If you read the earlier article and examine the pages of the 1st Edition DMG you will see that there are rules similar to those implemented by later editions, but you will also wish that the earlier edition had created cool graphic representations like those of later editions.

Zones of Control and Attacks of Opportunity in 5th Edition D&D

5th edition (in the Basic Rules) does take another slight step away from the miniatures trend and towards more abstract than the earliest editions of the game with regard to flanking. I would argue that 5th edition is the first edition with takes "no position" with regard to miniatures and carefully crafts descriptions so that combat can be run either with or without miniatures without using house rules or dropping rules regarding opponents being on directly opposite sides of an opponent. In this way 5th edition is the “least D&D” edition in terms of Zones of Control and miniature use. However, it should be noted that 5th edition rules still refer to "squares" from time to time. The 5th edition still includes Opportunity Attacks - a firm Zone of Control concept - as described on page 74 of the Basic Rules. But instead of listing a specific amount of distance moved as in Moldvay, 1st AD&D, and later editions it merely lists the need to use the "Disengage" action. The Disengage action can be used with a tactical map, but doesn't require one as it is more narrative in its description than the older "Defensive Withdrawal."

The Rogue class on page 27 show the basic flanking rules for 5th edition which does not entail a good deal of examination of figure placement to see if combatants align properly on opposite sides of an opponent in a way that require illustration. Under Sneak Attack, the Basic rules state that you can deal extra damage if you have advantage OR "if another enemy of the target is within 5 feet of it, that enemy isn't incapacitated, and you don't have disadvantage on the die roll." That's a pretty big shift toward simplicity and away from map use. While it could be argued that the 5 foot rule implies the use of maps, one could easily assume that a creature engaged in melee has an enemy within feet. Since this replaces needing opposite sides for advantage, this is a boon for mapless gaming but a boon that allows for the continued use of maps. It is easily adaptable regardless. So what does this make 5th edition's Zone of Control rules based on the Basic Set?

5th Edition D&D: Attacks of Opportunity (strong ZoC) and flanking benefits with certain attacks if another enemy of the target is within 5 feet of it.

In early editions of the game, the rules were presented in Wargame terminology. By 3rd Edition AD&D, they had become somewhat much more specific in the description and presentation and Zones of Control were still deeply rooted in "threatened" effects. So much so that the company felt the need to create a 3.5 edition of the game which specifically used miniatures to demonstrate how the combat rules work. The difference was the use of language. D&D by 3.5 had ceased using purely wargame language to describe combat effects, it had some of its own concepts. In fact, no edition of D&D used the term Zone of Control even though it is a common term in chit and map wargaming.

With the release of 4th edition, they returned to the older trend of using wargame terminology. They also added more conditional tactical capacities and wargame style effects became implemented in more areas of the system. By 4th edition, a game that had worked hard to feel less "game-ish" and more narrative in the 2nd edition of AD&D had returned to more wargame rooted mechanics that made it for some players too game terminology and tactically oriented. Players who used Wizards, especially Wizards who had Controller capabilities, could feel the "gamishness" of the system in abundance and it felt less narrative to them.

A part of the reason for the rejection of the return of wargame mechanics is because many players don’t have years and years of experience playing D&D in a way that aligns with the underlying wargame mechanics. Though Zones of Control were central to D&D’s combat mechanics from the very first edition, I don’t ever remember making an “Attack of Opportunity” prior to playing 3rd edition. This is even though the rules for withdrawal are very explicit and are featured in one of the very specific examples in the combat section.

We have had years upon years of stripping away the gamish stuff and substituting an array of cultural D&D rules that substitute for the Zones of Control and miniature heavy aspects of the game. Original D&D was as very much a miniatures wargame as is 4e, every edition between is actually as much a wargame mechanically, but we had created short cuts and systems to eliminate those elements and go to the abstract.

In doing so, I think we actually neglected some of the real richness of the game. We should celebrate the gamist pieces. Use them. Get used to them. Once they become second nature, they become less "game-ish" and you can focus on the story. The more you focus on ZoCs being annoying, when they've always been there but maybe you ignored them, the less you are enjoying a great game.