Why I Love Old School Dungeons & Dragons

I am also currently running a 5e game.

"I was busy rescuing the captured maiden when the dragon showed up. Fifty feet of scaled terror glared down at us with smoldering red eyes. Tendrils of smoke drifted out from between fangs larger than daggers. The dragon blocked the only exit from the cave.

Sometimes I forget that D&D® Fantasy Adventure Game is a game and not a novel I'm reading or a movie I'm watching." — Tom Moldvay, D&D Basic Set (2nd Edition), 1981

Those are the opening words of the Foreword to the 1981 Tom Moldvay Dungeons & Dragons Basic Rulebook as edited by Tom Moldvay and for me they get at the heart of why the game has remained popular over time. I’ve discussed in the past how my first D&D experience was absolutely terrible, but there was something about the experience that left me craving more.

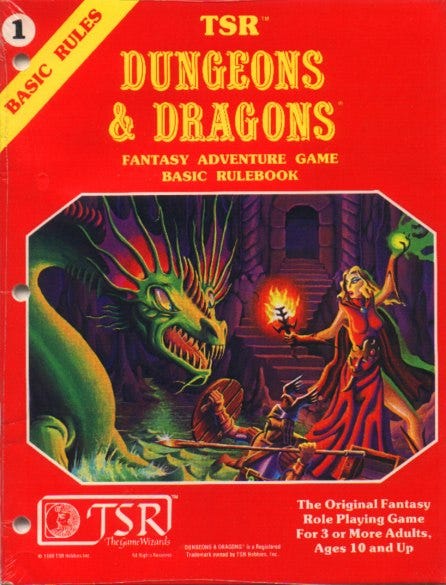

My parents noticed my interest and went to a local store and purchased a hodgepodge of game books for that year’s Christmas presents. When I way hodgepodge, I mean exactly that. They purchased an older and out of print version of the Basic Set (the Moldvay version), an Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Monster Manual, a Fiend Folio, and some lead miniatures that were old enough to have already oxidized. I was overjoyed with the presents and spent the rest of Winter Break reading these books, not quite realizing that they were actually for different games.

When I opened the Basic Rulebook and read Tom Moldvay’s Foreword, those words sparked my life long love with the role playing game hobby. The Foreward contains a simple, even simplistic, introduction to a fantasy tale. It features one of the most cliche story lines in all of childhood tales, the rescuing of a maiden. Even at the time the rules were written, the trope was a stale and long worn trope. It was such a stale trope that the film Dragonslayer, a rare truly magical fantasy film from the 80s, used a reversal of that cliche as a central component to its narrative. For my money Dragonslayer is one of the best fantasy films Disney ever produced, and maybe the best Fantasy film of the 1980s.

One of my favorite fantasy novels, Simon Green’s Blue Moon Rising (1991), also features a very fun inversion of the trope and Robert Heinlein’s Glory Road (1936) has a similar but different inversion of the hero and princess trope. In the case of Heinlein, it’s an inversion that mirrors the end of Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World (1912) and Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899). Seriously, read those two books back to back. The way Doyle’s ending draws upon Conrad’s earlier work reminded me of reading H.P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness. after reading Poe’s Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym. It was clear the writers were in dialogue with one another.

The trope may have been stale, but Moldvay’s scenario captured my fantasy loving soul. The imagery of "smoldering red eyes" and "fangs larger than daggers" was more than enough to capture my childhood imagination.

It is often said that "the Golden Age of Science Fiction is 12," meaning that what each reader considers the Golden Age of Science Fiction is the literature they read when they were 12 years old. While there is some small amount of truth to that, I do have a fond spot for the fiction I read when I was 12, but it isn't always the case. In fact, my favorite Science Fiction and Fantasy, and those I think are canonical "Golden Age" classics. are stories I read in my 20s and 30s. What's ironic is that the stories I read in my 20s and 30s are the traditional classics, while the stories I read when I was 12 where the avant garde rebels of Science Fiction’s New Wave.

My 12 year-old Golden Age Fantasy is Moorcock's Elric & Corum, Donaldson's Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, and Cook's Black Company and my Golden Age Science Fiction is William Gibson’s Neuromancer, Michael Moorcock’s Behold the Man, and the stories in Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions. It wasn't until I was older that I gained a true appreciation of Tolkien, C.L. Moore, Kuttner, Heinlein, Asimov, Burroughs, Howard, and so many others. Let’s just say that Behold the Man being one of my favorite “Classic” Science Fiction novels shapes things when people call something transgressive. Behold the Man features tropes that were shocking at the time it was written, but were as hackneyed and cliche as the princess tale in my read canon by the time I read it. Yet there are still those pushing these same ideas today as if they are “interesting,” innovative, or boundary pushing. I think they are interesting, but as for innovative and boundary pushing, nah.

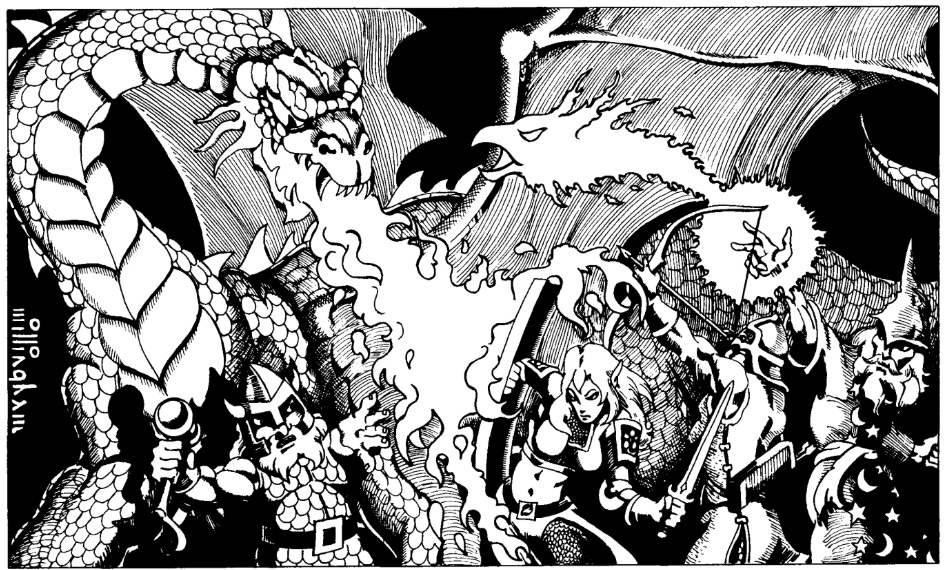

Given my referential baseline of Fantasy literature, Moorcock, Donaldson, and Cook, it might seem odd that Moldvay's Basic set would be the one that set my imagination alight. The book's line art, most of it by Bill Willingham, Erol Otis, Dave LaForce, and Jeff Dee, is a far cry from gritty and looks closer to the art that would be featured on the D&D cartoon or in Disney’s Sleeping Beauty than it does to the covers of a Black Company or Elric novel. Those stories deal with the evils of corruptible men and women or eldritch horrors that spawn from Chaos itself. Yet, to this day, when I think about what is best about D&D, I think about the Moldvay rules.

Tom Moldvay's editing of the Basic Set presented the D&D rules in a clear and easy to understand manner that left little ambiguity in my young mind regarding how the game was played. Having read the Original Little Brown Books that were the first public presentation of the D&D rules, I now understand what a remarkable task this was. Yes, Moldvay was following in the footsteps of Dr. Holmes' first Basic Set and was able to stand on the good Doctor's shoulders.

Dr. Holmes first Basic set presented D&D's rules in an intelligible way, but the rules were written for the older teen to adult gamer. Tom Moldvay's rules, as should be evident by the fact that his "Appendix Moldvay" of recommended readings is filled with Young Adult and Kid's Literature, were designed as an introduction for the young gamer. That's what makes the edition so strong. It presents rules that could be described as arcane and mysterious, in a manner that most 10 year olds could begin running a game within a couple of hours...and they'd be enjoyable hours of reading. Not just because of the clearly written prose, but also because of that lovely line art.

One of the things that is lost in a lot of the more recent versions of Dungeons & Dragons is a connection with the wider literature of the Fantasy Genre. No, I’m not complaining about the people that are playing the game and their chosen style of play, rather I am highlighting how Dungeons & Dragons has become its own genre of Fantasy. The original D&D or Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson was informed by Wargaming and tales of Sword & Sorcery. It was essentially inspired by tales of Tomb Raiding, wealth accumulation, and war. That is good fun and has a connection with a great literature. The Basic Set, with its very different Appendix of recommendations, is tied more to mythology, Epic, and works of High Fantasy thematically. The rules can be brutal, but the Known World setting, later Mystara, is filled with wonder inspired by an older genre.

These games, and the AD&D game, inspired authors who wrote books based on their campaigns like Raymond Feist’s Magician (and the whole Midkemia saga) or Andre Norton’s Quag Keep. Eventually TSR, the publishers of Dungeons & Dragons began publishing their own Fantasy novels with the Dragonlance Saga and early books set in the Forgotten Realms. With the Dragonlance books you could “see the dice roll” from time to time, but when Rob Salvatore wrote his Drizzt books for the Forgotten Realms setting the connection between rules and fiction became even stronger. In his first trilogy, published when AD&D was still the major rules set, Drizzt goes berserk when he is fighting Giants in a manner reflective of the rules for the Ranger Class at the time (they got +1 point of damage per level vs. Giant Type creatures). In the second trilogy, Drizzt’s retraining from Fighter to Ranger mirrors the Dual Class rules of D&D (though those normally only apply to humans) and he’s ambidextrous because all Drow are in the rule books.

There are examples galore in the Drizzt books and I don’t think these detract from the books at all, but that’s because the books serve a dual purpose. They need to be compelling Fantasy, and they are, but they also need to be Dungeons & Dragons Fantasy because a goal of the books is to get people to play the game and the game experience should match the narrative experience. In essence, by connecting the rules and fiction so deeply Dungeons & Dragons has become its own genre of Fantasy. Over the years that genre has evolved with the rules and even gone through waves so that former lines of fiction don’t align as well with the modern rules.

I love modern Dungeons & Dragons and I like playing the heroic adventures, but the modern game is connected to the Dungeons & Dragons genre of Fantasy. If I want to play adventures based on older versions of Fantasy, and to break out of predictable play, I tend to play AD&D or the Moldvay Basic version of the game. It’s less structured and more free form. There isn’t a rule for every circumstance and so players often ask if they can do things they might not attempt in a more granular game, what I call the mechanics based mentality.

You don’t need to play Apocalypse World or City of Mist to escape the mechanics based mentality, though those are great ways to do it, because you can do it will Old School D&D. Do yourself a favor. If' you've never read this edition, go back and read the Moldvay Basic Set. It's a bargain and well worth giving a try.

The Red Box and especially the Errol Otis artwork are a true nostalgia trip for me. I got my Red Box back in 1983 as I had been introduced to D&D by my good friend but I wanted my own set of books. I actually cut my teeth on AD&D but stepped back to Basic as I could just afford the Red Box and that gave me more than enough to be creating characters and start adventuring with other friends.

Basic just let you quickly create characters, set them up and gather your party before setting forth upon high adventure. And because it was a limited version of the game, it was easier to grasp how the game ran. It just worked.

Well said!