Weekly Geekly Rundown for September 1, 2023

No preamble this week. I wrote too much about my recommended role playing game below.

Weekly Luke Y Thompson and Courtney Howard Film Article Cavalcade with (possibly temporary) addition of Alison Foreman

Luke Y. Thompson’s Review

Luke’s only got one review for us this week and that’s his review at SuperHeroHype for season four of Star Trek: Lower Decks.

Courtney Howard’s Entries

Since I’ve got a lot, A LOT, of contextual commentary around Courtney Howard’s film review this week, none of which are critiques of her review because it’s a great read, I wanted to make sure that you checked out her coverage of what Gareth Edwards’ had to say at a sneak peak event for The Creator. There’s a lot of really cool information in that piece about how the film was made and I couldn’t find any plot spoilers. Made me even more excited to see the film.

Courntey’s review of Choose Love is very critical and focuses on the challenges of creating engaging material in an interactive format, a challenge that Netflix has yet to really master. Before I get into some of the reasons I think Netflix is particularly bad at this, I’d like to take a moment to say that Choose Love initially appears to have a sold foundation. The screenwriter, Josann McGibbon, has a nicely balanced resume for a saccharine rom com and I love a good saccharine rom com. She is credited with the story for Three Men and a Little Lady, wrote Runaway Bride, and wrote for both the whimsically edgy series Desperate Housewives and the edgily whimsical Descendants movies for Disney Channel.

While I have my quibbles on the edges with Runaway Bride, it was produced during the peak rom com era and stands out as a memorable addition in large part because of scripted moments. Yes, Julia Roberts always brings charm, but she has material to work with here, though as I mentioned it’s rough around the edges. The Descendants series also has its rough spots, but the stories have good heart and the series is much better than its production values.

As with the Descendants movies, McGibbon’s material has a truly charming actress in the lead role. Dove Cameron was a delight in those films (though Sofia Carson really steals the show sometimes) and Laura Marano is another actress from the Disney machine who exudes charm. In my opinion, this combination of McGibbon and Marano provides the potential for a very entertaining romantic and comedic film. However, and it’s a big however, interactive films are hard to do and Netflix isn’t the best at them and the romantic comedy format adds another challenge.

Tom coms have to stick the ending. For every film like You’ve Got Mail that has me weeping at the end with joy, there are at least a dozen films where I’m only mildly satisfied. Family Man had the potential to be a great romantic comedy/Christmas remarriage film. It didn’t fail because, as critics said at the time, that it was cliché and predictable. It failed because you fell in love with his family and that family cannot and will not happen. The daughter you came to love, never comes to be. It’s a God Damn heartbreaking ending that is selling itself as cute. About Time, one of the best romantic comedies and one of the best time travelling films ever, understood this concept of family and used it as a conflict in the film. A bad ending kills a good rom com and an interactive rom com needs to stick multiple endings. That’s a challenge.

Additionally, a good comedy is a constant series of setup, joke, setup, joke. When the comedy is of the “screwball variety” like Monkey Business or Frazier, that constant series has almost no gaps. With other comedic films, we sometimes have to way for the payoff to a joke that was setup much earlier in the film and the anticipation is what makes it work. Either formula can work, but both require narrative flow. Interaction interrupts that flow.

All of these challenges are things that people who write for the video game understand. The various relationships you can engage in while playing Baldur’s Gate 3 have extremely interesting outcomes. Yes, you CAN make choices that lead to bad outcomes, but my relationship with Shadowheart (yeah, I’m a Shadowheart stan) has some really nice moments. Those moments are made even more powerful because I have a pretty good understanding of Forgotten Realms lore. The thing is, I’ve had to walk a tightrope of choices to make that relationship work and have had several opportunities to screw it up. That’s because Baldur’s Gate 3 is a genuinely interactive experience in a way that a Netflix film cannot achieve without interrupting the narrative flow and taking the viewer out of the experience in a way that activates their “critical eye” as Jon Boorstin highlights in his book Making Movies Work. In fact, it was this problem that Courtney highlights when she writes, “It’s difficult to be fully immersed in Cami’s world as the film’s problem-solving demands our active participation.” That active participation might be worth it if the end pays off, but Courtney reveals that all of the endings are unsatisfying. Why put in work for a mid relationship?

Alison Foreman’s Entry

Since I’m a fan of good film lists, and since Alison has been showing that she is able to create, and/or participate in the creation of, some pretty good “should watch” lists, I’m sharing her 12 Best Car Movies from Christine to Titane list. As with the lists I shared in the last Weekly Geekly, all the movies on the list are bangers. There is not a bad film on the list, but I’m left wondering if they are all “car” movies. Sure, they all feature cars, but I can’t help but wonder how a list that is supposedly prompted by the streaming release of Fast X doesn’t include any of the films from that franchise. Additionally, the lack of films like Rush, Grand Prix, Talladega Nights, The Last American Hero, and Heart Like a Wheel seems to exhibit a strange definition of car film that excludes movies that involve racing. The exclusion of The Last American Hero (based on the Tom Wolfe article about Junior Johnson) and Heart Like a Wheel stand out in particular. So too does the exclusion of Smokey and the Bandit and Duel. I’m not demanding that the list include cult material like Ron Howard’s Grand Theft Auto or Paul Bartel’s Death Race 2000, but Baby Driver and the original Italian Job would have been nice to see there.

See…that’s why lists are hard and it’s why I rarely if ever use the term “best” when I write one. The only thing you can really ask is that every entry on a list be good and Alison’s list is. Oh, yeah, I almost forgot Drive Angry and The Car and since the list includes The French Connection, you absolutely must watch this episode of Corridor Crew’s Stuntmen React where they talk about how the chase scene was filmed. They are lucky people didn’t die.

Roleplaying Game Recommendation

I was talking with my students before I started my lecture yesterday and I stated boldly, “can you even claim to be a fan of comic books if you don’t have at least strong opinion that runs contrary to the ‘expected’ opinion?” It’s a class on political polarization and as in politics geek communities have different factions. In comic books it used to be DC vs. Marvel, but it’s begun to overlap with politics and as it has done so the dynamics have become more complex. Similarly, there are factions in the role playing game community and there are opinions you are “supposed” to have. Just like the supposed to like film list I wrote about in the last Weekly Geekly (linked below), there is one for role playing games too.

When I was younger, I was supposed to hate Chill and 2nd Edition Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. Chill was an overly simplistic game that didn’t have the “complexity” of Call of Cthulhu and 2nd Edition was an abomination because it removed demons and devils and was made by “she who shall not be named.” The fact is, I loved both of those games. I’ll likely include a full review of Chill as Halloween approaches and 2nd Edition was an amazing time for D&D game settings. Name your favorite setting that isn’t Greyhawk or Mystara and it was either created for or expanded in wonderful ways for the 2nd edition of AD&D. Heck, AD&D even got me to like Bards for a time. That liking has passed as people have forgotten the lessons of 2nd Edition and returned to Bards all having the same narrowly defined personality.

More recently, there have been two games that really blew me away but were rejected by large swathes of their fanbase. The first is Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay 3rd Edition, which I have defended and will defend again, but the second is 4th Edition Dungeons & Dragons which is my role playing game recommendation of the week.

Critics of 4th Edition tend to fall into three main areas of complaint. The primary attack is that the game is “nothing but combat and doesn’t encourage role playing.” I’ve got a long post in the hopper for you, it will be delivered tomorrow by email, discussing how every edition of D&D is highly tactical in nature and encourages the use of miniatures (though I think Baldur’s Gate 3 also shows the benefits) and that complaints that 4e was more “wargamey” than earlier editions is wrong.

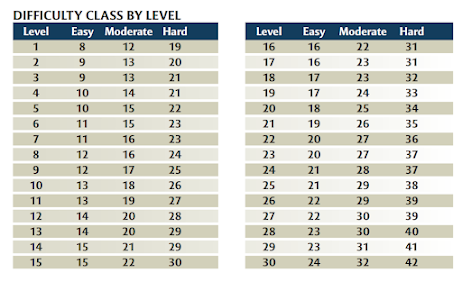

That discussion only addresses half of the complaint though. The other half of the doesn’t encourage role playing complaint often stems from the shorter skill list and how skills work in 4e. While I could be pithy and say that these people should read page 42 of the 4th Edition Dungeon Master’s Guide, I won’t. I’m going to take them seriously, while still arguing against them. The fact is that 4th edition because of its shorter list of skills actually encourages MORE role playing than 3rd edition does.

Let me take a moment to step back so you can let that soak in for a moment. The first edition of D&D had exactly zero skills. No class had them at all. Fighting Men didn’t have skills, neither did Clerics or Magic Users. By the time we reached AD&D there were eventually two kinds of skills, outside of “class skills.” These were secondary skills, which were completely abstract, and non-weapon proficiencies which were more specific but which a lot of the gaming community at the time didn’t like. They seemed to be an attempt to make D&D more like Runequest or Champions where skills were narrowly defined, though in Runequest at least almost every skill had a default level. Eventually with 3rd Edition, these kinds of skill lists became deeply embedded in the rules allowing for players to play simulation games where they managed taverns merely by rolling dice to see how profitable their tavern was each day. The higher the skill check for “Profession: Tavern Owner” the more they made. D&D had become a randomized simulation of even mundane activities.

While having the ability to know how much your character earns from a performance or day of tavern management, or what percentage of the eventual GP total necessary to manufacture a longsword the character completed that day, can be useful there is a dark side as well. The problem with skill lists of these kinds is that there is a tendency to say “if you don’t have the skill, then you can’t try it.” I saw this happen in abundance on the Green Ronin message boards during discussions of the 1st Edition of Mutants and Masterminds. Steve Kenson’s original intent was to have players of characters like Reed Richards take “Super Intelligence” and have that bonus apply to all of their science skills. Reed Richards is great at all science after all, but the 3.x gaming community had become wedded to the more granular skill lists and attacked his design and demanded that players be able to spend character points on skills instead. They were of this “if you don’t have the specific skill you can’t do it” mentality. I think the game got worse for it and I was happy to see when 4th Edition had reduced the number of skills available. I didn’t enjoy the “roll playing” of crafting items and running taverns. Those are things that don’t need skills, but only role playing. In my opinion 3.x was the game that hindered role playing, but it was the lack of these same skills that had people crying out that 4e was the perpetrator.

I’m not attacking these people for saying that. Many of them had played since earlier editions, long before skills had become a central part of the design. I am saying that they had gotten so used to having the structure of granular skills that it limited their ability to see how removing that scaffold could actually increase freedom to role play rather than roll play. Why do I think this? Because 5e is almost universally lauded as encouraging “role playing” more than 4e, but it does so while having very similar skill rules and a reduced skill list. 5e and 4e are pretty much the same here. 5e is slightly more abstract in combat, but not that much in reality. The difference was in marketing, rather than in game play.

Speaking of marketing. The marketing of 4e was the second major area of complaint. Players felt like the marketing was attacking them for liking the game. They were absolutely correct. The marketing team did the game no favors with their marketing campaign. Below, I've embedded the D&D 4th Edition Teaser marketing video. You can watch the whole video and you can feel the meta-cognitive irony and seeming disdain for earlier editions of the game. In particular, I'd recommend watching at 1:31 for the "Okay, what is THAC0 again" question and to 2:26 to see how the 4th edition marketing represented 3.x by mocking that version's rules for grappling.

The entire video is filled with snide commentary and the THAC0 and grappling jokes, while representing genuine critiques of those editions by some players, have a mocking feeling. This is a tone that 5th edition largely managed to avoid until "THAC0 the Clown" in the recent Witchlight adventure, a joke that foreshadowed the attacks on the fanbase of January and February of this year.. The unifying thing between the 4th edition marketing and The Wild Beyond the Witchlight is Christopher Perkins. Perkins has written some of the best D&D content out there for several editions of the game, but I find his repeated mocking of THAC0 staid. At least he waited until later in the 5th edition cycle to pull out the anti-THAC0 joke from the dustbin. Had this attitude been evident earlier in 5th edition, rather than the "we love the old editions so much that Keep on the Borderlands is our playtest module" attitude, the game might not have gotten off to the great start it did and Critical Role would have continued promoting Pathfinder instead of D&D.

The final thing that I think killed 4e in many players’ minds was the presentation. Back in February of 2011, a couple of years into 4e, Robert J Schwalb who worked on the 4e design team, wrote a blog post asking if "the format matters." In that piece he wrote:

Fourth edition’s presentation abandoned nearly everything familiar about the game’s look. Eight years of 3rd edition, I think, created strong expectations about how the game should read and since the game didn’t match the visual expectations, it certainly must not match the play experience. Yes, there are considerable mechanical changes that alter the play experience somewhat, but compare how the game plays now to how the game played in the twilight of 3rd edition. Just look at Tome of Battle, Complete Arcane, and many of the variant rules presented in Unearthed Arcana (complex skill checks, healing surges, and so on). In them you can find the proto-rules that would eventually evolve into the mechanical underpinnings of 4e. They are different, but not as different as I imagine some folks believe. I wonder if those changes might have been more palpable had we shifted back toward the old presentation, even if doing so meant that the game would be harder to learn.

Let's have a look at what Robert's reformatting of the Cleric (now I wish I'd selected the Cleric for the others) looked like. Note that Robert hasn't filled in all the content, so don't worry about the lack of text. Just look at the layout. One thing that should strike you is how this looks exactly like 5th edition playtest materials and that it looks very similar to 3.x's layout. Had the design team opted for a presentation like this, it might have been slightly less shocking and been one less hurdle to overcome in order to minimize edition war effects.

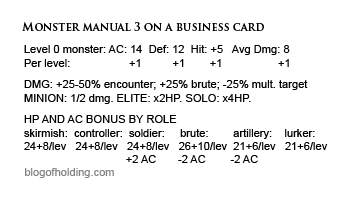

That’s a lot of time spent addressing the critics of 4e, but I’d like to take a moment to advance the virtues of the game. The design team for 4e created a game that is easy to understand and that plays quickly at levels 1 to 10. Given the basic power level of characters in the game, that’s the sweet spot for play any way. The characters start off feeling heroic and get to the point where they are pretty powerful. The game changes significantly after about level 16 and combats can become extremely long affairs. Yes, you can run the whole game with nothing but a Monster Manual on a business card, but even with that convenience the time it takes for high level fights to finish is off putting to some. This isn’t true of low level fights. Those are quick and engaging.

If you are using the Essentials rules, which are the rules I most recommend using, there are tons of interesting options without any of the bloat. Give it a try. Oh, and the Points of Light setting and Nentir Vale are a fantastic game setting.

Music Recommendation

I’m going to go extremely mainstream today, in part because I heard this song in the car with my daughters this morning and it’s been an earworm all day. The fact that it’s been an enjoyable earworm suggests that I might want to recommend it. Bruno Mars’ “Locked Out of Heaven” is a song that features a number of influences, but I love the guitar work in it and his voice is amazing as always.

Classic Film Recommendation

Today’s classic film recommendation is an absolute must see noir film starring James Stewart. Otto Preminger’s Anatomy of a Murder (1959) is one of the great legal procedural films to ever hit the silver screen. Like Preminger’s later film The Human Factor (1979), the characters have many different underlying motivations. These are complex characters. In the case of James Stewart’s character, his goals are to gain revenge on the person who pushed him out of office as a prosecutor and to build a financially successful law practice. To do this, he coaches his client carefully with regard to how to plea a case. He coaches witnesses and engages in moral behavior akin to Perry Mason in the books, but without the benefit of having a client who is clearly innocent as Mason always does. It was one of the rules of Mason stories that his clients be innocent of the crime of which they are accused (note the qualifier). There’s a reason that the author set up a pro-bono defense firm with his earnings.

Stewart’s clients are also complex. Key among them is Lee Remick’s character who fluctuates between noir vamp and innocent. The scenes where the character attempts Stanwyck-esque seduction and sophistication reveal that she is no femme fatale. That doesn’t mean she’s not beautiful or that responding to her advances isn’t dangerous, it just means that the danger lies elsewhere. Remick is phenomenal here and so is Ben Gazzara (the villain from Roadhouse) who is a wonderfully creepy client.

I should note that I watched this at the same time that I watched the first six episodes of David E Kelley’s The Practice from the 90s. It was amazing to me how much Kelley took from Anatomy and transformed it with some additional character layers to make a very different story, but both cases follow similar through lines. One ends in a noir fashion and the other ends with a just outcome. My only complaint about Anatomy is the cinematography. The Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where the film takes place and where much of it was filmed, is a beautiful location and we never get to see its beauty nor the danger that some of that beauty provides.

Cool beans. Anatomy of a Murder is a classic, and while I may not have enjoyed the first season of Lower Decks, I might give it another chance since Luke gives season 4 high praise.