The Scare-athon Continues: Scary Season Week 4 and 5

Sorry I’m Late on This

This year I am attempting to draft my longest movie marathon recommendation list to date. I’ve done seasonal recommendations before, but I’ve never done one that would require the recommendation of over 60 films over the course of nine weeks. Yet here I am, a little late due to the worst flu I’ve had in years, with my fourth entry of recommended films for you 2025 Movie Scare-athon. Because of the time I spent down and out with a major brain fog, I’ve decided to give a full 14 recommendations in this entry.

The recommendations of the first two weeks lacked any theme and were just films that I have a general love for and think anyone and everyone should watch. I’m particularly enamored of all the film in my Week 1 recommendation list. If you were to ask me what my “top 10” or “top 20” horror films were, most of the films in Week 1 would make the cut.

By the third week, I decided that it might be easier to make recommendations if I had a theme for each week. In Stephen King’s book on writing, he demonstrates pretty strongly how setting limits can actually open up creativity by providing an immediate structure beyond the blank page. Asking oneself “okay what are the next seven horror films I am going to recommend?” is a very different question than “what are seven horror films based on the Classic Universal Monsters I can recommend?” Both are challenging, but one is less challenging than the other.

Last week’s theme was Family Friendly Horror films and for weeks four and five, I am providing a list of seven Science Fiction Horror films. These films will range from the scientifically realistic to the almost fantastic and some might not quite fit your definition of a horror film, but I consider them all to meet the basic standards of horror presented by H.P. Lovecraft in Supernatural Horror and Literature in that they all deal with fear of the unknown.

The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown. — H.P. Lovecraft, Supernatural Horror in Literature, 1927

The Quatermass Xperiment (1957)

By the time the Sputnik 1 satellite wasn’t launched into space in October 1957, the Space Race was in full swing and science fiction tales of rockets. The dangers associated with sending people into outer space were still very much unknown. How would we protect astronauts from the radiation of the Van Allen belt and what would be the long term effects of exposure? These were questions we did not have the answer to, but we knew we needed to win the Space Race and achieve dominance in near space.

The Quatermass Xperiment is an exploration of the potential dangers associated with sending astronauts into space. After the British-American Rocket Group, headed by Professor Bernard Quatermass (Brian Donlevy) launched the first crewed rocket ship into outer space it crash lands upon return with all of its crew members deceased, save one. Victor Carroon (played by Richard Wordsworth) is the surviving astronaut, but he didn’t survive unphased. His body is slowly mutating, changing into something that threatens all of mankind.

The movie is fun and is the first in a number of Quatermass adventures produced by Hammer Studios. This entry was directed by Val Guest, who did a number of films for Hammer and who worked primarily in lower budget genre fare including a relatively entertaining entry into the Robin Hood mythos.

Quatermass is a character I’d love to see revived by modern cinema. There was a remake of The Quatermass Experiment serial back in 2005, but I think Quatermass stories would work best as either pure period pieces or with entirely new storylines. Like Doyle’s Professor Challenger, there’s room for exploration and expansion with the character and the tension between the benefits of science and the risks associated when it explores the unknown are well worth dredging.

GOG (1954)

GOG is the perfect encapsulation of the Patriotic Red Scare Cold War Science Fiction Horror film. The movie opens with two scientists being mysteriously murdered by an unknown force/assailant. The scientists were running an experiment to prove that their method of cryogenic freezing would allow people to be sent into space to explore worlds light years away. The initial experiment, involving a capuchin monkey, is a success, but one of the scientists becomes trapped in the freezing room when he is cleaning up after the experiment. His frozen, shattered then thawed, body is discovered by another doctor, who finds herself trapped in the same space to experience the same fate after reacting to the horrific outcome.

This accident leads the complex’s chief of security to contact the Office of Scientific Investigation to send David Sheppard (Richard Egan) to determine the cause of the deaths and if there is a saboteur at the hidden scientific base. Over the course of the film, we are introduced to the N.O.V.A.C. supercomputer and its two robot assistant’s Gog and Magog (love the biblical reference there). While the film is very direct in its story telling, one can easily see how this production influenced later films like The Andromeda Strain and 2001: A Space Odyssey. This film is a fun little jaunt and there are a couple of pretty creative methods used to eliminate the scientists in the secret base. Is this a case of a rogue computer, or is something else to blame for the malfunction?

The Andromeda Strain

Robert Wise is one of Hollywood’s great directors. He’s produced masterworks in every genre ranging from B-Movie horror like The Curse of the Cat People, where he replaced director Gunther von Fritsch, to family friendly musicals like The Sound of Music. I’ve long enjoyed his 1950s Hollywood epic Helen of Troy, though it is very 50s, and his financial drama Executive Suite builds wonderful tension by highlighting the pressures of Wall Street long before “Greed was good.” Wise’s The Haunting is one of the best traditional ghost films ever produced and even his uneven productions like Star Trek: The Motion Picture get much better with age as you reset your expectations to evaluate the film for its actual merits rather than compare it to some imagined best Star Trek film.

Wise’s approach to adapting Michael Crichton’s about a mysterious microscopic organism that crash lands in New Mexico was to produce a highly realistic film grounded in realism and procedure rather than in jump scares or shock. Crichton’s book, like most of his work, was a critique of scientific elites. In this case, Crichton added a nice dose of Cold War paranoia to the mix as well. While the micro-organism is highly lethal, the real threats in The Andromeda Strain are human failings like arrogance and secrecy that might lead to the destruction of mankind. Michael Crichton loved science, and I think was optimistic about what it could do, but he was highly critical of people. In this case, he’s critiquing the willingness of experts to lie in order to participate in a potential breakthrough as well as the government’s willingness to use nuclear weapons as a failsafe.

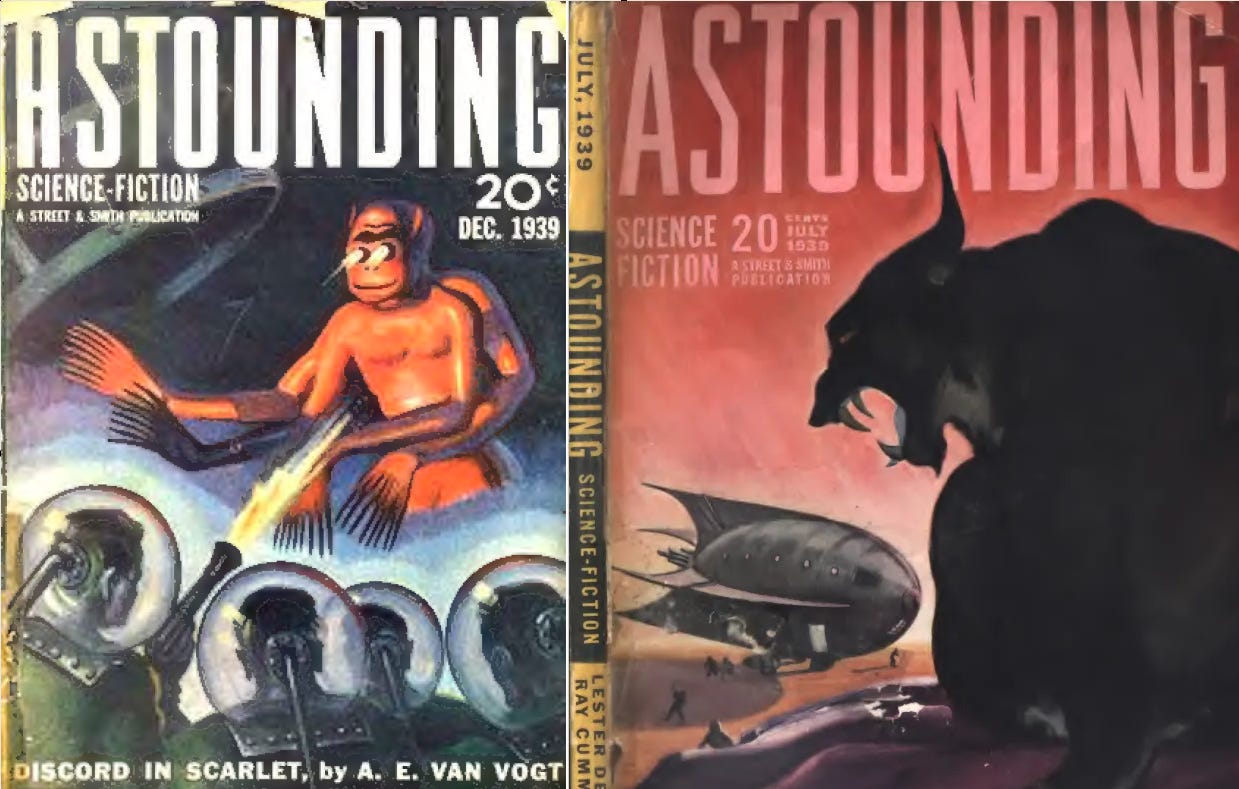

Forbidden Planet

In my opinion, Forbidden Planet is the singular best adaptation of William Shakespeare’s play The Tempest. Yes, it takes a ton of liberties, but it has the same wonderful exploration of the costs of pursuing power and knowledge. Here the stakes of the cost are raised and transformed through the lens of Golden Age Science Fiction tropes. By the 1956 release of Fred Wilcox’s special effects spectacular, and viewed through a retro-science fiction eye Forbidden Planet remains a visual spectacle, the novelization of A.E. van Vogt’s Voyage of the Space Beagle tales had already been in print for six years and van Vogt’s Slan had been out for a decade. It’s very clear to that many of the Campbellian/Vogtian ideas about human consciousness and capability, as well as the means of space travel, saturate this film.

This movie is the visual apotheosis of the Astounding era of Science Fiction and it is a beauty to behold. We’ve got Robby the Robot in the role of Ariel, serving Dr. Morbius in almost everything he demands or requires, but we also have “The Monsters of the Id” as the adaptation of Caliban. It’s a wonderful transformation of concepts and given the assaults of the “Monster from the Id” on the ship and it’s crew, it’s hard for me to imagine that screenwriter Cyril Hume and director Fred M. Wilcox were unfamiliar with van Vogt’s tales in Astounding. Forbidden Planet is unique enough that I don’t think van Vogt would have had a case against them, but this is pure Campellian science fiction right down to the heroism of the individualistic male.

Alien

Speaking of A.E. van Vogt’s influence on Science Fiction Horror films, what is possibly the greatest Science Fiction Horror film ever made had to settle a case against them by A.E. van Vogt after he claimed the film borrowed elements from two of his Space Beagle stories “Black Destroyer,” and “Discord in Scarlet.” If you read the stories, it’s easy to see the connections claimed, but I’ve always believed van Vogt had a much better claim against Star Trek as a franchise being essentially an unauthorized adaptation of his Space Beagle stories. From the “shields” to the inclusion of a Science Officer who had semi-psionic abilities to The Man Trap’s “salt vampire’s” similarity to the Coeurl of “Black Destroyer,” I’m surprised he didn’t sue CBS at the time. Sure, being a Vulcan is different than practicing the integrative self-hypnotic science of Nexialism (points of you know what real life organization is related to Nexialism), but there are tons of similarities.

For all that Ridley Scott might have borrowed from van Vogt, the story of Alien is far more distinct in its presentation of the themes than Star Trek ever was. Where both Star Trek’s screenwriters and van Vogt give us tales of highly trained and specialized scientists encountering the unknown and using their ingenuity to overcome obstacles, Alien gives us Space Truckers who are trying to deliver goods from one place to another and happen to stumble into a nightmare. The crew aren’t stupid, but they are completely unprepared for what they encounter and we as an audience get to experience one of the best science fiction films ever made that also happens to be one of the best horror films ever made.

Event Horizon

I imagine the pitch for Event Horizon went something like this, “What if we took the movie 2010 and instead of it being about encountering Space Gods, we made it about encountering the Space Devil?” Given that the director was Paul W.S. Anderson and the screenwriter also wrote the 2009 film The Mutant Chronicles based on the role playing and miniature skirmish games of the same name, I’m pretty sure I’m right in that fantasy.

I first watched Event Horizon when I was an undergraduate at the University of Nevada. My wife, who I was dating at the time, and I decided to drive to the Bay Area to go to Paramount’s Great America and ride a few rollercoasters to start of the new school year. We arrived in Santa Clara in the evening, checked into our hotel, and I asked her if she’d like to see the movie. She agreed and we were both scared out of our wits. Jody is not a big fan of horror films, so she was shaken up for a few days. I am a fan, but the film got under my skin in a way that is rare.

Between making the first actually good movie based on a video game (Mortal Kombat) and his work on Event Horizon and the Kurt Russell vehicle Soldier, I thought that Anderson would be on a path to artistic success. I was half right. He was on a path to financial success, much greater financial success than he achieve with what I think are his two best films (Soldier and Event Horizon). The performances by Sam Neill and Lawrence Fishburne are very strong in the film and whether or not the sources of the terror in Event Horizon are supernatural or psychological is left a little open to interpretation. One thing is certain though, this is one of my favorite cosmic horror films.

Sunshine

I’ve been a fan of Chris Evans for some time and think he was a great choice to play as Captain America, but the most impressive heroic role he has ever played is Engineer James Mace in Danny Boyle’s 2007 science fiction thriller Sunshine. The film takes place in 2057 where the Earth is slowly freezing because our Sun is slowly dying and the warmth it provides our planet is declining. The world is doomed unless a heroic mission using a ship called the Icarus II can implant a stellar bomb into the sun and reignite it’s sputtering flames.

A previous ship (the Icarus I) had been sent to attempt this same project seven years earlier, but had failed in its mission for unknown reasons. Over the course of film the mystery of why the initial mission failed is revealed and this new mission faces its own new challenges, both physical and psychological. The plot of the film is straightforward and it is the performances by Rose Byrne, Chris Evans, Cillian Murphy, Michelle Yeoh and everyone else that really make this film click. The film shares many tropes with Event Horizon, and would make a great double feature with it, but the result is a far more optimistic tale.

Coma

I try not to recommend films by the same writers/directors more than once a week, but in this case I’m making an exception. Given the focus on Science Fiction Horror, I probably could have made an entire week featuring nothing but Crichton films given the strength of his catalog. Besides, it’s not quite cheating to include a second Michael Crichton related film in the list this week because The Andromeda Strain was based on a book written by Crichton, but Coma is directed by Crichton and based on a book by Robin Cook.

Coma tells the story of Dr. Susan Wheeler (Geneviève Bujold), a surgical resident at Boston Memorial Hospital who begins to suspect that something sinister might be happening at the hospital when a patient receiving a relatively routine surgery ends up in a coma during knee surgery. She is romantically involved with Dr. Mark Bellows (Michael Douglas), another surgical resident, who she asks to help her as she investigates what she discovers might be a pattern of otherwise healthy people falling into comas after minor surgeries. The film has a great cast with Bujold and Douglas putting in strong performances and Rip Torn chewing up the scenery a bit. Tom Selleck has a nice cameo in the film that provides important evidence as the story moves forward.

The Thing

While Forbidden Planet is the film that best captures the sensibilities of the stories of the John W. Campbell era of Astounding Magazine, The Thing is the best adaptation of a Campbell story ever produced. The movie, like the earlier version The Thing from Another World, is based on John W. Campbell’s novella “Who Goes There?” The novella was published in the August 1938 issue of Astounding Science Fiction where Campbell published it under the pseudonym Don A. Stuart. While later editors like Lin Carter might have felt comfortable publishing stories they had written under their own name, Campbell typically used a pseudonym. Given how much “influence” he had on the content of his bullpen, almost every story he published might be considered a Campbell story. For example, Asimov’s tales of “the trader” in Foundation are paeans to capitalism in a way that perfectly represented Campbell’s strong libertarianism, but were very much at odds with Asimov’s own politics. The words were Isaac’s, but the societal arguments were Campbell’s. That, of course, is discussion for another time.

What is truly remarkable about Campbell’s story, and John Carpenter’s far more accurate adaptation of the story than the black and white classic, is how it merges realistic science and science fiction with horror elements drawn from both Poe (The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket) and Lovecraft (At the Mountains of Madness) with their focus with their focus on paranoia and isolation. The characters in The Thing quickly “realize that they are in a horror movie” and begin to act in mostly reasonable ways, especially for scientists who want to balance a desire to know with a need to survive. The movie’s ending is an all-time classic and fully captures the dread suggested by the original title. Who goes there indeed?

The Fly

David Cronenberg is one of the great directors of Body Horror films with classics like Shivers, Rabid, and Videodrome pushing the boundaries of what transformations and violations of the human body can be shown on film, so it is no surprise that his remake of the 1958 science fiction film The Fly leans heavy into visualizing the effects of the bodily transformation. The 1958 version of the film, based on George Langelaan’s short story, visualized the physical transformation in a manner that was less grotesque and focused on the humanity of the scientist over special effects. Cronenberg demonstrated that you could include all of the grotesque elements while heightening the psychological effects and discussion of the scientist’s humanity even more.

When people ask me if horror films replace genuine pathos with grotesque, I often recommend this film to them because as gross as it gets it is very much a touching and sad film. Chris Walas’ practical effects and makeup are striking, but they brilliantly capture both the physical and psychological transformation of the main character. Jeff Goldblum, who like Nicholas Cage can sometimes be a caricature of himself when acting in some films, is very strong in his performance here. Geena Davis, who was dating Goldblum at the time (they were married from 1987 to 1990), is excellent in the role and outside The Accidental Tourist I think it’s her best performance.

The Invisible Man

My recommendation list for next week focus on some of my favorite films featuring variations of the classic Universal Monsters, but not all of those recommendations will be for the early Universal releases that solidified those archetypes into the world’s horror psyche. That is especially the case with The Invisible Man as my favorite version of that tale is not the original, but that doesn’t mean the original isn’t brilliant because it is.

The 1933 version of The Invisible Man was directed by James Whale and it perfectly encapsulates a recurring theme of early science fiction horror, that the perceived power that comes with scientific advancements can corrupt those who create that power. Scientific advancements, without a moral compass, can destroy as much as they can empower and create and that is something we should always be wary of as moral people.

In this adaptation of H.G. Well’s novel , Dr. Jack Griffin has discovered a chemical version of the Ring of Gyges and created a formula that can make a person invisible. As with the ring, the effect morally corrupts Griffin and he begins his plan to use his invisibility to dominate the world through acts of terror and “a few murders here and there.” Things unravel rapidly for Griffin and Claude Rains, who would later perfectly balance corruption and honor in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, is absolutely fantastic here. While Rains gets a lot of praise, rightfully, for work he did under contract with Warner Bros., he really shines in this film and Whale’s direction is spot on.

Altered States

I mentioned in my discussion of The Devils in the second article in this series that I find Ken Russell to be an uneven director and that The Devils highlighted both his brilliance as a director and his flawed reliance of camp in some films, but his direction in Altered States is pitch perfect in tone. Altered States is a very 1970s film. The film is based in part on American psychoanalyst and counter culture researcher John C. Lilly, who along with Timothy Leary was a major advocate for expanding the consciousness. He gained renown for developing the isolation tank and researching how using them, and taking LSD while immersed, could expand the human mind. Ken Russell takes this super-Hippie basis, combines it with New Age elements that are straight out of Carlos Castaneda, and adds postmodern concepts of how our consciousness shapes reality (literally here) to create a very interesting experience.

William Hurt is very compelling as Columbia Professor Edward Jessup who is seeking to find a way to find new states of consciousness. He focuses on this to the point of obsession and this causes a rift between him and his wife. In his obsessive self-experimentation, heaven only knows how Columbia and then Harvard allow this, he eventually discovers that the hallucinations he experiences are more than mere shifts in consciousness. They are shifts in reality, first in his own physical self and then in…well, I don’t want to spoil the ending which is surprisingly romantic and hopeful.

Flatliners

I find Joel Schumacher to be a lot like Ken Russell as a director. When he is on target, he is one of the best directors in his chosen field (genre films) in the history of Hollywood. Any time I see The Lost Boys, Cousins (his remake of Cousin Cousine), Falling Down, Phone Booth, or even The Number 23 (a personal obsession of mine) available on streaming I won’t hesitate to watch them and enjoy them as very well made and well directed films that demonstrate talent and vision. Then there are St. Elmo’s Fire, 8mm, and the Batman Movies and I cringe as they either lack heart or wallow in camp. The overall scale, as it is for Russell, weighs in on talent, but the motorcycle chase scenes in his Batman films are so bad their taint wandered over into my The Lost Boys viewing experiences. I can never see those scenes the same way again.

Flatliners is a very solid entry in the science horror genre and tells the stories of five medical students who want to know if anything really does lie beyond the veil of death. They test this question by each experiencing temporary body death, only to be revived by the others and reporting back what they experience. It is what they experience that is the real driving force of the film as each must deal personal trauma, some that was inflicted on them by others but also some that they inflicted on others. While Schumacher can wander into camp when forced to deal with emotional moments in some films, the performances by Kiefer Sutherland, Kevin Bacon, Julia Roberts, and Oliver Platt are all very strong in this film.

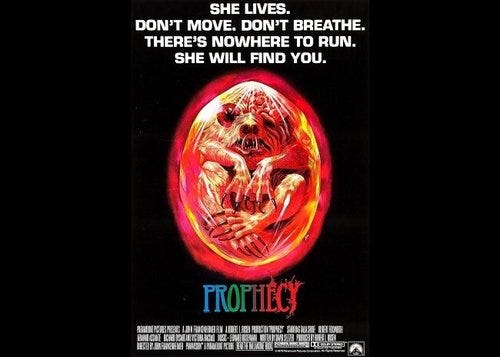

The Prophecy

While John Frankenheimer is typically associated with serious film fare like The Manchurian Candidate (which is great even if it features the worst hand to hand fight scene ever captured on film), Seven Days in May, Grand Prix (one of the rare good films about Motorsport), and Ronin, it is his strange film about a murderous creature in backwoods of the Northeastern United States that I find myself watching again and again. I can’t remember whether I first watched this movie with my dad or whether it was a Sunday afternoon film with my Opa, what I do know is that it scared the bejeezus out of me as a kid and that I’ve loved it ever since.

Like Altered States, The Prophecy is very much a film that channels the zeitgeist of the 1970s. Where Altered States examined spiritualism and psychedelia, The Prophecy focuses on the environmental effects of industrialization and conflicts between corporations and Native American tribes. The Prophecy begins with three lumberjacks being killed by a mysterious force that the local Native Americans believe to be a Katahdin, a vengeful spirit, who is taking revenge against the loggers for the tremendous damage they are doing to the environment. The screenplay by David Seltzer (The Omen, Bird on a Wire) is strong and balances the themes of scientific mutation and supernatural revenge very well.

The movie was filled in British Columbia and is credited with helping to establish Canada as an alternate filming location for American sites and as always the particular beauty of the Pacific Northwest shines through as…the particular beauty of the Pacific Northwest. You can’t make British Columbia look like Maine anymore than you can make it look like Paris, Texas (I’m looking at you otherwise charming Netflix romantic comedy The Wrong Paris). One you’ve lived in the Pacific Northwest, you find that BC can substitute easily for Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana, but that’s about it. The topography is too specific, as is the natural light. The narrative also feels more like a story of the Pacific Northwest with the loggers vs. Sovereign Nation Land as a major tension.

That aside, the location shots are beautiful and the horror still holds up. I think this is a film that could be remade and it makes a great double feature with Nightwing (directed by Arthur Tiller and based on Martin Cruz Smith’s book of the same name), another excellent 1979 horror film about industry vs. Native American tribes that I’ll probably recommend in a future list.

Pop Punk Synopsis