The Most "Intellectual" RPG I Own. My Answer Might Just Surprise You.

I own a lot of role playing games and have owned even more over the years. While I am pretty sure that GMaia’s collection dwarfs my own, I’m pretty proud of the collection I have put together even as I miss some key entries that I hope to get back some day. I do dearly miss my copy of Superhero ‘44, not 2044 I’ve still got that one, but I can wait for a few years to bring that one back to the bookshelves. As it is, I am beginning to curate my collection to keep only those that have deep meaning for me or were important developments historically.

Like many who have a large collection, I’ve read far more role playing games than I have played. I have a long standing rule that I will only provide recommendations (pro or con) for games I’ve actually played, but I will often discuss other aspects of the games I own to place them into the proper historical context. For example, I have not played all the games I discuss in my series on Strange Licensed Role Playing Games — I have played most of them — but I am able to discuss them from a non-recommendation perspective and discuss why they didn’t connect with an audience. I believe one can discuss how a game innovates mechanics, why it did or did not connect with an audience, and a host of other topics having only read a game. I remain steadfast, though, in the opinion that you can only review a game that you’ve actually played. “Readviews” have their place, but they aren’t the same as a review.

All that preable aside, I’ve recently been pondering answers to a question that was asked in a meme a few years back as a part of the RPGaDay challenge run by the blogger autocratik. The original challenge was to write about a role playing game every day for a month. It evolved to include specific questions and in this past year’s evolution included a prompt mechanism that didn’t vibe with me. One of the prompts in a prior year was a recommendation to discuss what the most “Intellectual” game you owned was. There was no definition of intellectual provided and the prompt lead to a number of interesting responses on social media and in blogs.

In the non-ironic responses there were references to Nobilis (Dave’s own choice), Aria: Canticle of the Monomyth, Mage: The Ascension, and other games from the “avant-garde” or “post-structural” era of role playing game design in the 1990s and early 2000s. Many of these games pulled from mythology or philosophy for their thematic inspirations. For example, Mage’s central conflict is centered on how reality is constructed by the collective consciousness of humanity and how certain forces use that to “protect us” from harm. Like most games in White Wolf’s World of Darkness line of games, Mage draws heavily from theology, post-modern and post-structuralist philosophy, and anarchist politics.

In many ways, I think that those who highlight games from this era are doing a disservice to the many games that preceded the games of post-structural era, not to mention many games that came after these admittedly intellectual games. To be certain, the games of the post-structural era are very academic games. They delve into the ideas that literary academia was and which, in my opinion to its detriment, continues to be obsessed with and seems incapable of moving beyond. It is as if the critical dialectic has stopped with Foucault, Rorty, Bakhtin, or Baudrillard without a new antithesis. Political, in the sense of academic and not public politics, considerations and the need to publish or perish have us trapped critically and much of literary and artistic criticism reads like obtuse synopses of prior works. Baudrillard’s analysis is interesting, and it parallel’s the much more lucid writing of Daniel Boorstin in his book The Image, but it has become stagnant and staid or even cliche which has its own irony.

To be fair to the Critical and Post-Structural, they are better than the last hegemonic literary fad, Symbolism and New Criticism, that still taints high school education with its “why is the light on the dock in Gatsby green?” question. I also know the millenia long Aristotelian Rhetorical Hegemon annoyed the crap out of some of the Romantics. Criticism, like the subjects with which it engages, is a dialogue that takes place over centuries not decades. I am, however, the product of the digital age and I watch fads like Skibidi Toilet rage and burn out in a single year, only to be replaced for a moment by 6-7, and so I want the critical fads to shift at a faster pace.

That overly long tirade aside, I think that intellectual means more than reflecting the dominant theories in academia. When I think of whether an activity is intellectual, I tend to think of it in two categories. The first is of the “thought provoking” variety that is reflected in those philosophic and academic theories. The second way I think about intellectuality as activity is from the research perspective and how something deeply intellectual can be “well researched” akin to a dissertation or research paper.

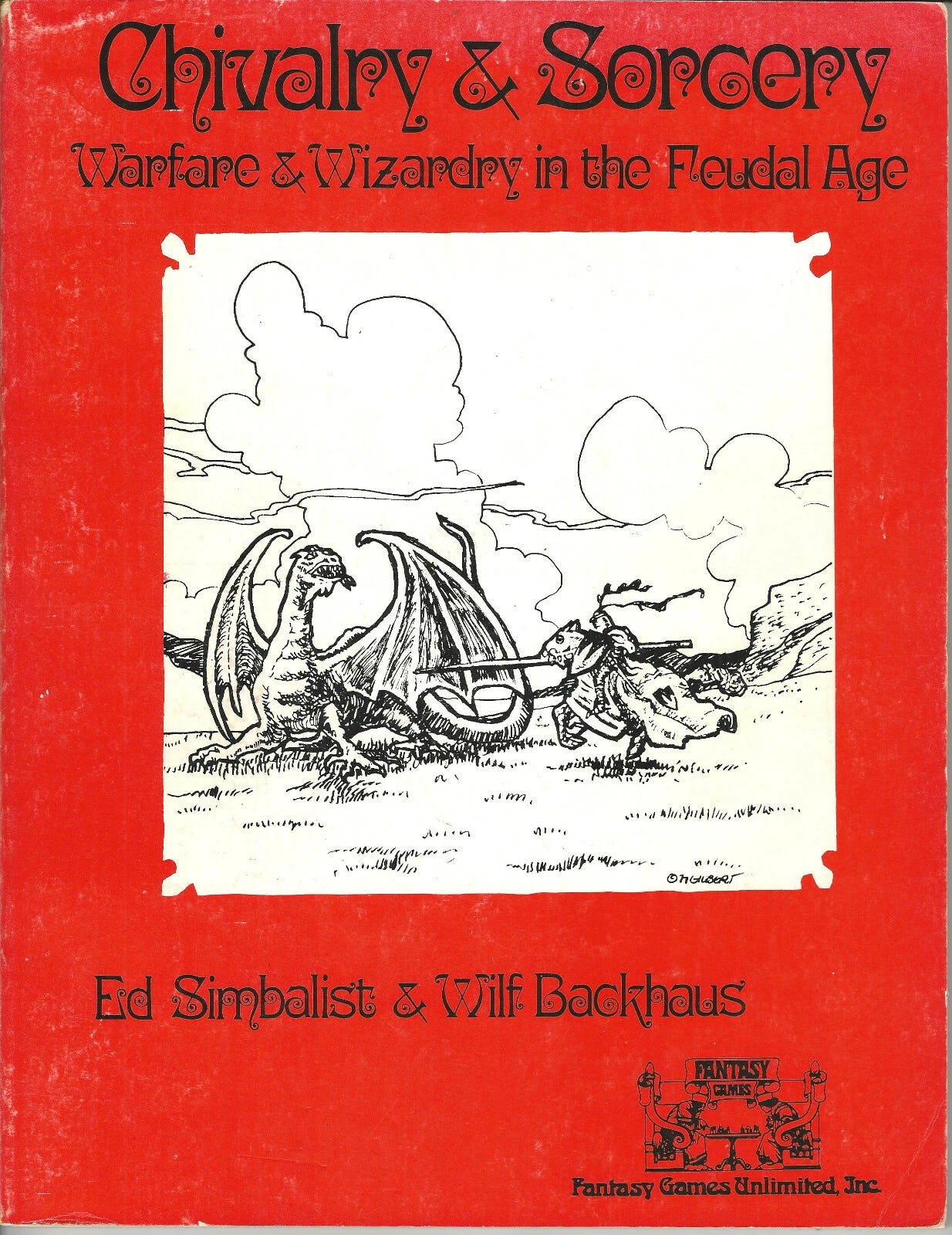

All of the games of the poststructural era qualify by both standards, but so do many others from much earlier in the history of table top role playing games. For example, it is impossible to deny that Chivalry and Sorcery by Ed Simbalist and Wilf Backhaus wasn’t a well researched role playing game and it’s one that only became deeper as more expansions were released for it. Sadly, the Fantasy Games Unlimited version isn’t available for sale as a pdf but it is a work worth investigating.

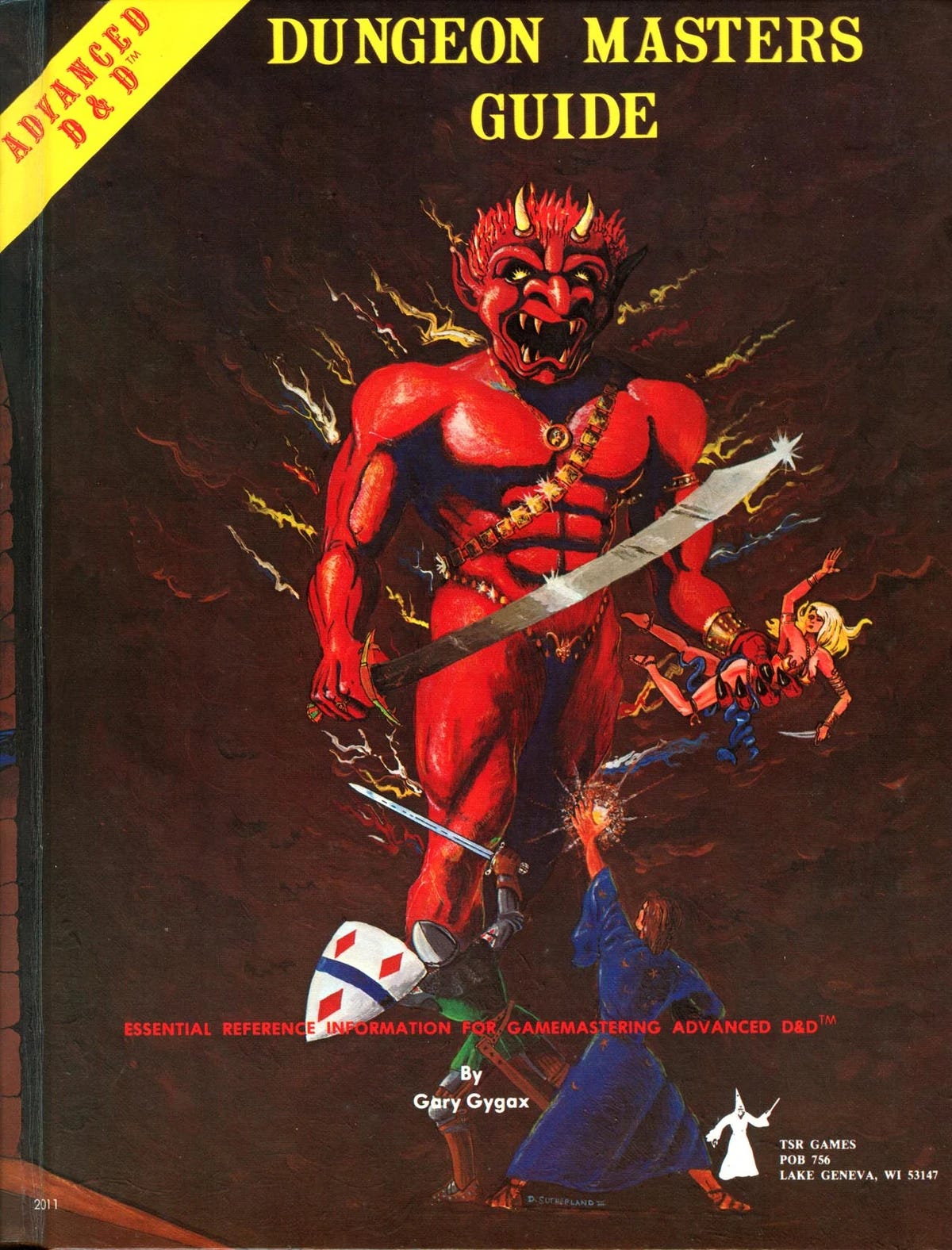

Gary Gygax’s work on AD&D also displays a combination of thought provocation and research that is often underappreciated by modern gamers. Gygax’s vocabulary alone is worth experiencing. Yes, there is a reason older gamers use the term “High Gygaxian,” but there is a lot that can be learned about gaming, vocabulary, history, and literature from the Dungeon Masters Guide alone. The famous Appendix N shows a deep understanding and appreciation for the Fantasy Genre. It’s not Lin Carter level, but it’s a great introduction.

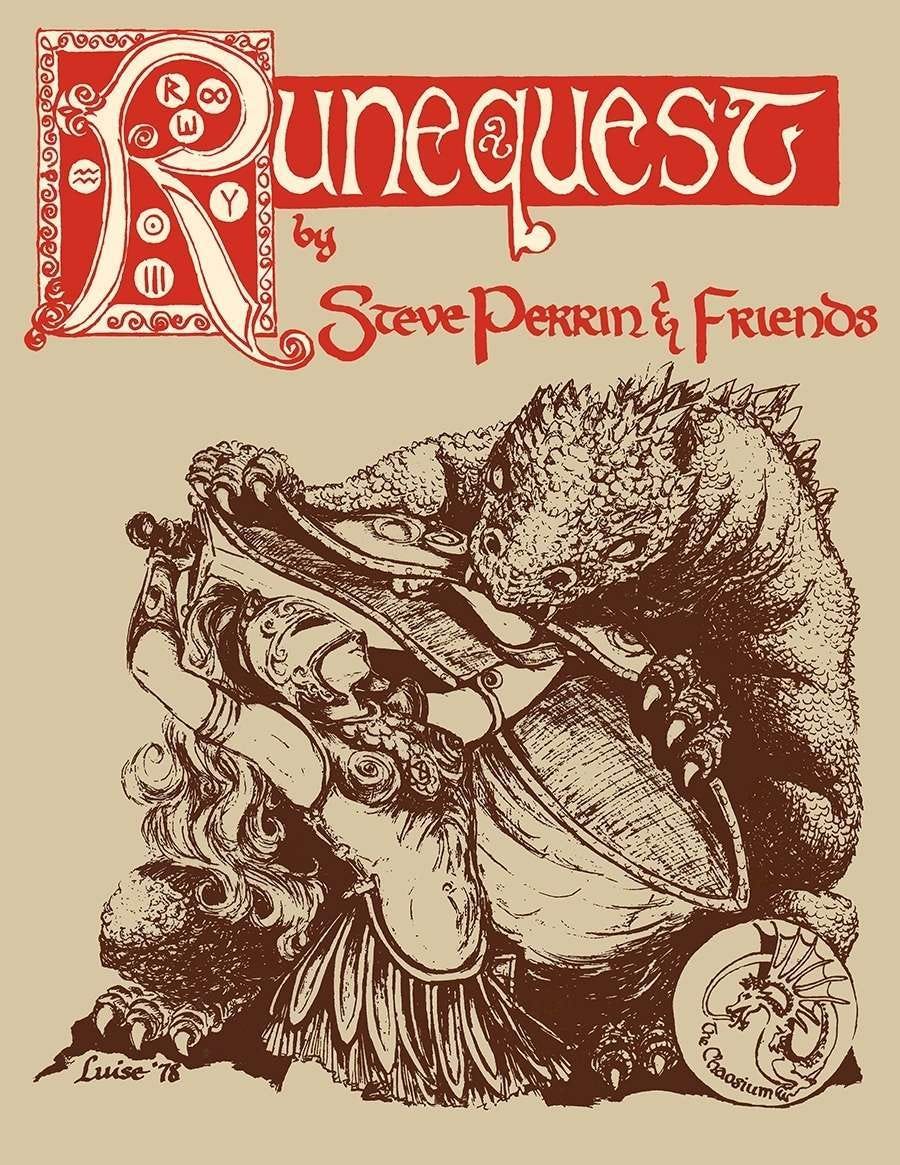

Steve Perrin and Ray Turney’s Runequest is a great game that is carefully thought out and it has a combat system that mirrors the rules used by the SCA in its tournaments. This is no accident as Perrin’s participation in the Society for Creative Anachronism provided the foundation for what he thought combat should feel like in a game. When it comes to the game though the real mythopoeic marvel is its use of Greg Stafford’s Glorantha setting. Greg Stafford was a true student of paganism and mythology and his expertise lives on in his presentation of faiths in his Glorantha setting. There is so much there thta provides intellectual fodder regarding the origins of faith in general and how we believe (or don’t) as individuals.

Tom Moldvay’s Lords of Creation touches on many of the issues that the later “artiste” games cover. Players eventually level up to become a “Lord of Creation” themselves, which is an interesting approach at showing players tht they have acquired enough knowledge and experience with the game that they too can become a game master who makes new worlds.

There are many others of the classic era of gaming - I didn’t touch upon Empire of the Petal Throne for example - but there are also more recent games like Lacuna, My Life with Master, or the controversial Vampires by Victor Gijsbers. Vampires is an attempt at a deconstructionist roleplaying game, but requires an explanatory essay. The essay and the conversation around the game are thought provoking and touch on why I think that safety tools are absolutely necessary for Victor Gijsbers game even as I think they are largely unnecessary in general. All three of the recent games are iconic examples of story telling games that fall squarely in the postmodern school of design.

I own all of the games mentioned above, but not one of them is the game that I believe to be the most intellectual game that I own. That game is a game that combines scholarship and mechanical innovations, and is thought provoking about how we should approach tales of fantasy. That game is Joseph Goodman’s Dungeon Crawl Classics. The game was inspired, and is informed, by the author’s intellectual desire to understand the literary inspirations that influenced Dungeons & Dragons. Goodman read the entirety of Appendix N for the purpose of learning about D&D and this led him to desire to create his own RPG. Given the length and breadth of Appendix N, that’s a pretty scholarly effort in my opinion and worthy of praise. His game balances mechanical innovations and nostalgia. It also fosters discussion as to what exactly the purpose of role playing is and expands our understanding of the intersection between older literature and modern game play.

Blast from the past! Nice to see that old game of mine still lingering on in its undead existence. :-)

After I jumped ship from 5e, DCC looked exactly like what I wanted out of a game that didn't stray too far from the tradition of gaming I grew up in. I still have yet to run a full, proper campaign with it, but it's the sort of game I'd use for my own secondary world (other than the system I'm developing for it).

I think it's the best thing to show, in this day and age, to more recent players in the hobby to explain what the inspirations for D&D were and exactly how strange they could get.