As I was uploading my second Geekside Chat, I was wondering how I should approach writing the written article below the video. Should I model the text on the way my journalist friend approaches it with scattered comments and links/videos providing context to the content of the chat? Should I print out a copy of the transcript and let you read the content instead of watch it if you want, or should I write thoughts that are parallel to the discussion in the video that provide context and hopefully get you to watch the video?

I opted for the third option and am going to write some brief thought about why I decided to do this particular chat and provide some links to things I referenced, or should have referenced, in the video. I’ll make clear what I actually discussed in the video and what is only in writing here, just to make it even more confusing/useful.

So…what inspired this second Geekside Chat and what is it about?

When it comes to how I view popular culture and pop criticism, I’m a bit of an odd duck. My primary belief is that it is the pop culture critic’s job to champion the overlooked or to provide history and context for pop culture that modern audiences might lack. While culture might be a continuous dialogue between the past and present, that dialogue sometimes gets muddled like a game of telephone and conversations in the middle might accidentally eliminate older and valuable contributions to the cultural conversation.

For example, a recent review I read of Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein was surprised that the Hermit had a family in the new movie since the blind man is usually alone. This is only a surprise to someone who has only engaged with the story cinematically and I think it’s worth talking about the literary elements as well. I don’t think the critic should be shamed or scolded for not knowing the textual reference, that’s just a part of the conversation and demonstative that the filmic Monster is better known than the literary one. I think a critic’s job is to discuss the literary reference to bring that back into the conversation because it provides evidence that the Monster is an unreliable narrator.

I am also pretentiously anti-pretense. Which is to say that like any other critic, I am pretentious enough to think that my opinion holds enough value to share and be read by others. I see myself as someone well-versed in pop culture and with the ability to write and talk about things at both a high and low level. If I’m not THE authority on the topics I discuss, I do view myself as AN authority. There are certainly those who know more than I do about everything I know, but I know a good deal about many things and I take pride in that. There’s pretention to that pride. However, I despise it when others same common entertainment or the common consumer. I made my feelings about the toxicity of critics and fandom in my essay about The Eye of Argon, a book often claimed to be the worst fantasy story ever written. For the record, it isn’t. There are worse stories. Worse stories that have been published and earned the author a paycheck, but I will also champion many of those.

These two sentiments combined recently when I watched a video discussing how the American Fantasy Genre, and Fantasy in general, had been “destroyed’ at its birth by a corporate minded editor. The video borrowed heavily from a Slate article from a couple of years ago, but added a jumbled and asynchronous timeline to it that undermined the criticisms. After all, if one wants to argue that Michael Moorcock’s Epic Pooh is an attack on post-Del Rey Fantasy, and in particular Terry Brooks’ Sword of Shannara, then the essay should at least mention Brooks and not focus on Tolkien, Lewis, and A.A. Milne. Moorcock’s work was an attack on “Reactionary” fantasy, fantasy that favored the bucolic over the urban and that argued in favor of traditional values over progress. Hence why he likes the Progressivism influenced Wizard of Oz more than Lewis’ Narnia. The Silver Slippers are very much a reference to William Jennings Bryan’s Cross of Gold speech and the Silver Movement. It is a book about the creation of a new order where Lewis’s pines for the bucolic and mourns the loss of faith, an argument that becomes more explicit when you think about the “Problem with Susan.”

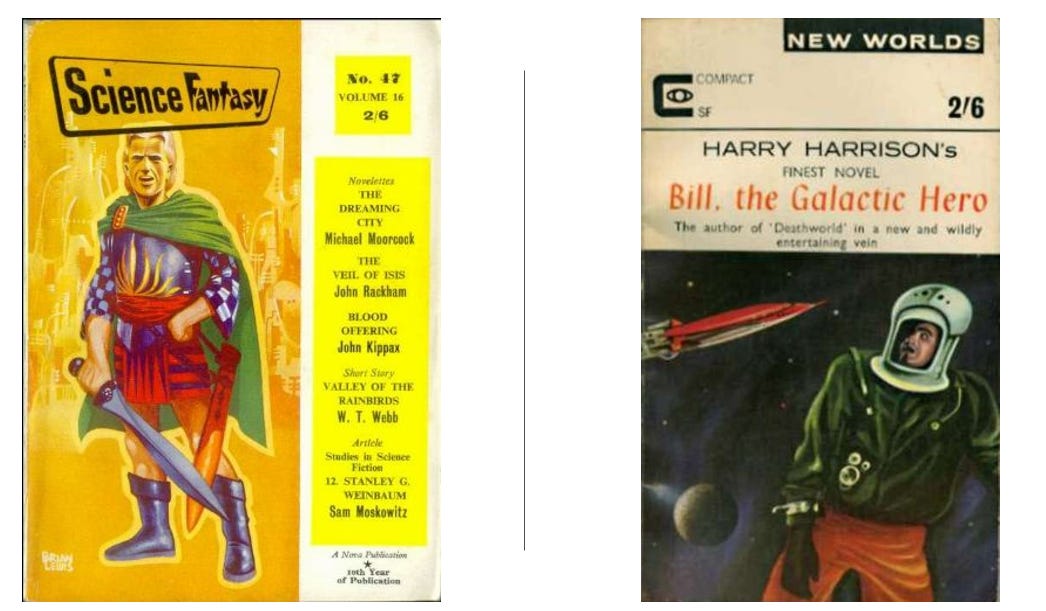

Anyway, the video argues that Del Rey killed fantasy by making it formulaic, more on that in a minute, and that Moorcock’s fantasy was a reaction to Del Rey-ian Fantasy. It cannot be denied that Moorcock was a champion of the New Wave in Science Fiction and Fantasy of the mid-1960s. As Moorcock wrote in his introduction to the 2002 edition of Harlan Ellison’s New Wave call to arms Dangerous Visions, Moorcock’s New Worlds was the European equivalent of what Ellison would do with that seminal New Wave Counter Culture SF anthology. Moorcock had introduced his Jerry Cornelius character, the SF Elric, in the August 1965 issue of New Worlds in the story Preliminary Data, an issue that also introduced Harry Harrison’s Bill, the Galactic Hero who deconstructed a lot of the Space Westerns of the pulp era. Moorcock’s Elric had already been introduced in the June 1961 issue of Science Fantasy magazine. Elric himself a deconstruction, a loving one as I mention in the video, of Conan the Barbarian. Compare their introductions below and see the parallels, which become more explicit in later tales.

Hither came Conan, the Cimmerian, black-haired, sullen-eyed, sword in hand, a thief, a reaver, a slayer, with gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirth, to tread the jeweled thrones of the Earth under his sandalled feet.” — The Nemedian Chronicles

The point of this is to highlight that Moorcock was remaking fantasy as early as 1961 and that Harlan Ellison, as I mention in the video, sought to remake Science Fiction in the same way a few years later. All of this is before del Rey became a publisher of Fantasy and is not a reaction to it. In fact, in an even greater irony, Del Rey was an active part of Ellison’s revolution. I mention in the video that many critiqued and attacked Ellison’s movement as a kind of parricide, an attack on the older generation of writers themselves, but that this argument falls flat because Dagerous visions includes many of the older authors. It wasn’t a critique of the writers, rather an argument to move the WRITING forward. Among the old guard who contributed to Dangerous Visions were, Larry Niven (young, but an old guard stylist), Poul Anderson, Theodore Sturgeon, and… Lester del Rey. In fact, the first tale in Dangerous Visions was a del Rey story.

If I wanted to support the argument that del Rey wanted to destroy Fantasy, I might argue that he thought that Science Fiction was the truly revolutionary and worthy genre and that Fantasy was staid and formulaic and so he only published to a formula, which others then follow. But as much as the Slate article attempts to say del Rey pushed the formula, the output of the company argues against such a push. Yes, Sword of Shannara (which I love BTW), cribs a ton from Tolkien and is relatively formulaic in doing so, but the second book is literally about a guy guiding the woman he loves through danger so she can become a tree.

Setting that aside, let’s look at some of the other books Del Rey (publishers) released in 1978, the year they released Shannara. We’ve got Patricia A. McKillip’s Riddle Master of Hed, which is very influenced by Celtic myths (as I mention in the video Moorcock would hate this, but it’s not Tolkienesque), Gordon R Dickson’s The Dragon and the George (a complete subversion of the tale of George and the Dragon) which I accidentally attribute to David Drake in the video because it was spontaneous, Anne McCaffrey’s Dragonflight (which features dragons in name only and breaks pretty much all of the rules in the Slate article), some classic E.R. Eddison, Peter Beagle’s The Last Unicorn (which is a classic that had been a part of the failed Ballantine Fantasy series), Jack Chalker’s Midnight at the Well of Souls which combines Fantasy and SF, and Stephen R. Donaldson’s Lord Foul’s Bane which asks us to root for a pretty awful protagonist. That leaves out the Edgar Rice Burroughs and a ton of reprints of classic, pre-Tolkien, fantasy. That’s a trend that continued.

Then there are the accusations of formula and how bad it is. UGH! I hate it when people say “that was predictable” or “I knew what was going to happen by the end” as if those are actual critiques. A well written story should lead logically to its ending. You should be able to predict the ending of a book if all the information is provided. Maybe it shouldn’t light up the ending in neon, but most stories should resolve as they should resolve. The “surprise” ending, and there are some good ones, only work if the clues were there all along. If they aren’t, it’s a cheat and a con by the writer.

Also, I love formulas. They are great. As I mention in the video, I go to romantic comedies to see people fall in love and not to watch them wander away from one another and lose hope in humanity. I mention three films in particular, all of which I think are perfect films, that I love. The Shop Around the Corner, In the Good Ol’ Summertime, and You’ve Got Mail. Not only do they all follow the same formula, they are the same movie and THEY ARE ALL GREAT!

I went in to watching the newest two knowing they were remakes and completely formulaic and I loved them. They also managed to charm and surprise me. Not by going out of formula, but by having interesting characters who breathed with their own life and personality.

Okay, I am writing way more than I wanted, just as I talked more than I wanted, but I’ll leave by saying that the argument that the critical video (and no I’m not linking it) that there is no American Tolkien is just wrong. We have a Tolkien level author and I name him in the video. Don’t even get me started on the greatness, and originality that is the Fantasy fo Manly Wade Wellman (who I don’t mention in the video at all).