Gaming History: Trust But Verify, TSR Buys SPI

John O’Neill, the publisher of the publisher of Black Gate Magazine was recently sharing his adventures emptying out his old storage unit on Facebook. Like me, John is an avid collector of games and novels who has more stuff than he can ever play. In fact, reading his posts reminds me of the my two week curating rush prior to my move from Los Angeles to Idaho. I was not able to bring my full collection up north and ended up donating a ton of my games to charity. Whoever went to the Goodwills in Glendora and Glendale in November of 2020 would have found a treasure trove of gaming items. I still have a reasonable collection that rivaled John’s own, but now my collection is much more humble.

His recent posts inspired me to visit the Black Gate site and read through some of his older posts including one he wrote back in 2012 celebrating an old SPI game called Swords and Sorcery. It was an article I had fond memories of reading when it was originally published, and I experienced a bit of nostalgia as I read my comments to the article. He praised the game in his semi-regular “new treasures” column. The game itself was published in 1978, but O’Neill had just acquired an edition from eBay. If the edition he purchased is the edition photographed in the blog post, he and I own the same edition of the game. The game may have been old, but it was new to him and I still have yet to play my own copy. It’s one of my “to play” bucket list games.

What is interesting about Johns review is that it inspired an age old conversation about when TSR acquired SPI and the terrible aftermath of that purchase. These conversations, much like conversations of Lorraine Williams’ management of TSR, are based on the common “known” lore that has been passed through the gaming community via Forums and Fanzines for decades. Among the grognards of the gaming hobby, of which I am certainly one, there is often a good deal of ire aimed at TSR for their behavior. This ire is often directed at Lorraine Williams, but not always. One of the rare cases where it isn’t directed at Lorraine Williams is in the TSR purchase of SPI in 1982. At that time, the company was very much in the control of Gygax and the Blumes, who were experiencing tons internal strife at the time regarding the direction and management of the company.

In this particular post, Black Gate’s former managing editor (the talented author Howard Andrew Jones who is sadly no longer with us) was the individual who brought up TSR’s “killing” of SPI product lines. As I mentioned earlier, I replied to the article. In my typical provocateur fashion, I mentioned that I thought that the TSR acquisition and killing of SPI was more complicated than most grognards think and even included some slight praise for Lorraine Williams. Yes, I am one of those. I am a TSR fan who will praise Lorraine Williams from time to time. Was she a terrible manager whose choices led to the demise of TSR? Yes, but she was also the head of the company during a heyday of amazing gaming content. I am actually amazed at the products that came out during her tenure, even if she hated gamers. Here is what I wrote:

While it is easy to blame TSR for what they did to SPI — and they deserve a lot of blame — one should keep two things in mind

First, when they purchased SPI it was in dire financial straights and would likely not have survived.

Second, they had hoped to keep SPI’s staff, but those staff members refused to work for TSR — for varied reasons — and left to form the Victory Games studio over at Avalon Hill.

Third, and this is where I get near heretical, it was the Blumes who devalued SPI’s contributions. A massive resurgence of publishing of SPI games happened under Lorraine Williams. We would never have seen the SPI monster TSR World War II game, or Wellington’s Victory, SNIPER (including BugHunters), let alone the 3rd edition of DragonQuest.

I believe she did the publishing of SPI stuff out of desperation, not any love for the product or the fans, as TSR was starting to have financial troubles which could only be met by an ever expanding publication schedule and continual revenue flow.

It was the Blumes who refused to acknowledge lifetime subscriptions to SPI magazines.

There is an excellent issue of Fire and Movement, printed by Steve Jackson Games, that goes over the purchase of SPI.

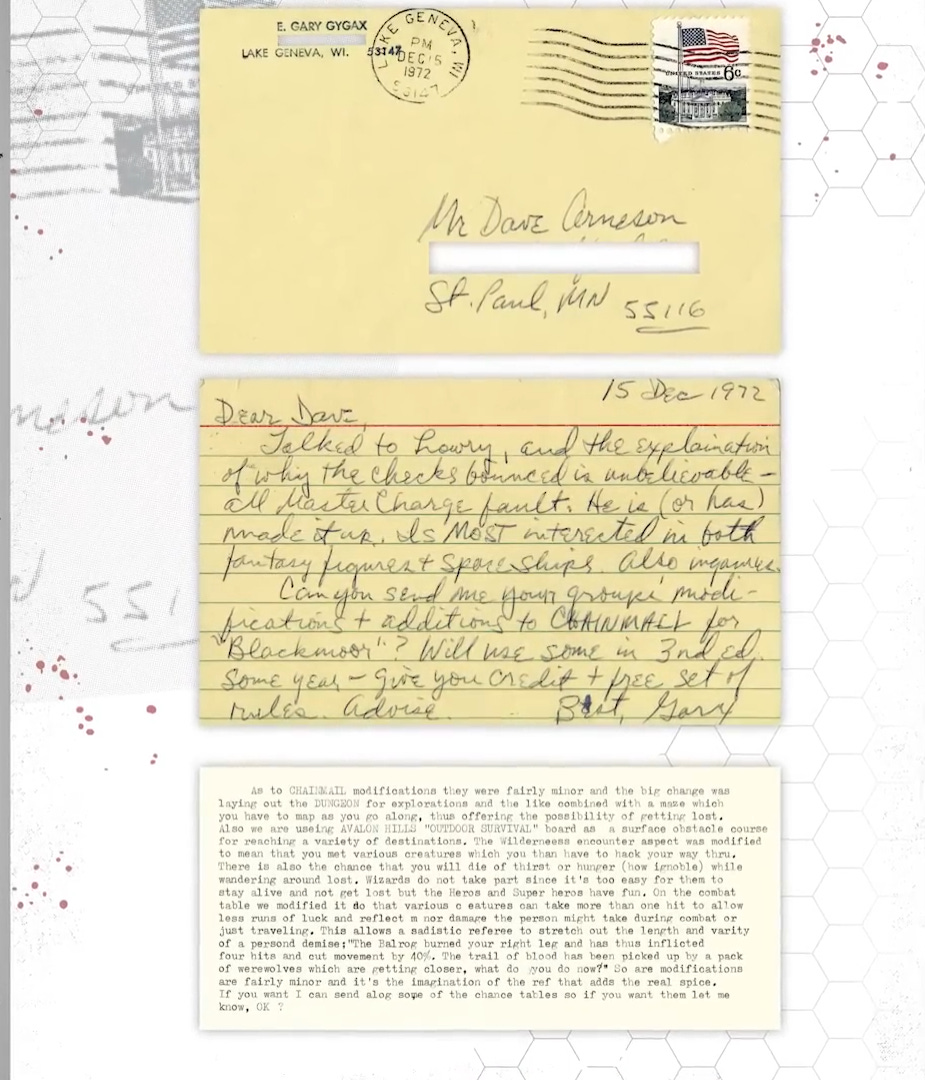

I eventually hunted down the issue of Fire & Movement. It is issue 27 (May/June 1982) and that issue adds a ton of real time context to the purchase of SPI by TSR. So much so that it serves as a reminder that when dealing with internet TTRPG lore, it’s best to “Trust but Verify” any and all of the common understandings of the hobby. One of the recent arguments, that fits this mantra, is the discussion of whether anyone ever used Chainmail when playing the Little Brown Books of D&D. Many of the Old Guard assure us that they never did, and yet there are a couple of contemporary pieces of evidence that disprove that. The first is a postcard from Gygax to Arneson, sent after Gary played in Arneson’s Blackmoor game (an experience I discussed in an earlier post). In that postcard, Gygax asks Dave to send his “modifications and additions to Chainmail for Blackmoor.” To which Dave responds “as to Chainmail modifications, they were fairly minor and the big change was laying out the Dungeon for explorations.” He capitalizes Dungeon in a way that might suggest he is referring to Dave Megarry’s boardgame, which was heavily inspired by Chainmail’s combat system.

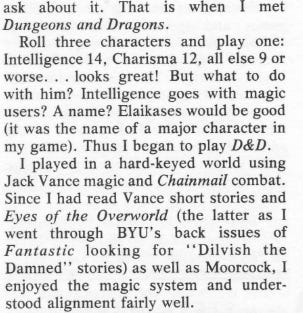

The second piece of information, that I’ve found, is an entry from Different Worlds Magazine issue #1 where Steve Marsh describes his early D&D playing experience. Steve Marsh was very influential in late 70s and early 80s D&D and is responsible for the addition of Good/Evil to the Alignment matrix as well as being the editor for the Dungeon & Dragons Expert Set. In that issue, Marsh talks about how he discovered D&D in his religion class at BYU. You’ll note that he states explicitly that he used Chainmail for combat. While we know that the Alternate Combat System, the d20 system, became the lingua franca of D&D combat, it’s wrong or disingenuous to say “no one played using Chainmail for combat.”

Back to TSR’s purchase of SPI and how the common knowledge in that is wrong. If we look at Fire & Movement #27, there is an article by Nick Schuessler of Steve Jackson Games that provides a remarkably detailed article about TSR’s acquisition of SPI and provides some context for the purchase. It is an article written at the time of the purchase and that interviewed participants in that takeover. Some highlights of the article are:

On March 31, 1981 TSR announced they were initiating a chain of events to purchase SPI.

On April 7th, eight key SPI staffers tendered their resignations and announced they were forming a new company called Victory Games that would work under the auspices of Avalon Hill.

TSR acquirexd the trademarks and copyrights of the entire SPI inventory.

Mark Herman, the leader of the eight defectors, had been negotiating with Avalon Hill to purchase SPI.

The TSR conglomerate owned a science fiction magazine (Amazing), and a needlepoint company, in addition to D&D and in 1981 they had $17 million in sales revenue.

SPI was a $2 million a year company.

Schuessler’s article is heavy on facts, and only has one bit of speculation. That bit of speculation is whether the brain drain, the loss of Mark Herman and crew, will have a long term negative effect on the acquisition. I would argue, from a historical perspective, that this was the single most devastating part of the acquisition. SPI’s strength was in its designers. Mark Herman, Jerry Klug, John and Trish Butterfield, and Greg Gorden were some of the most talented designers of their era.

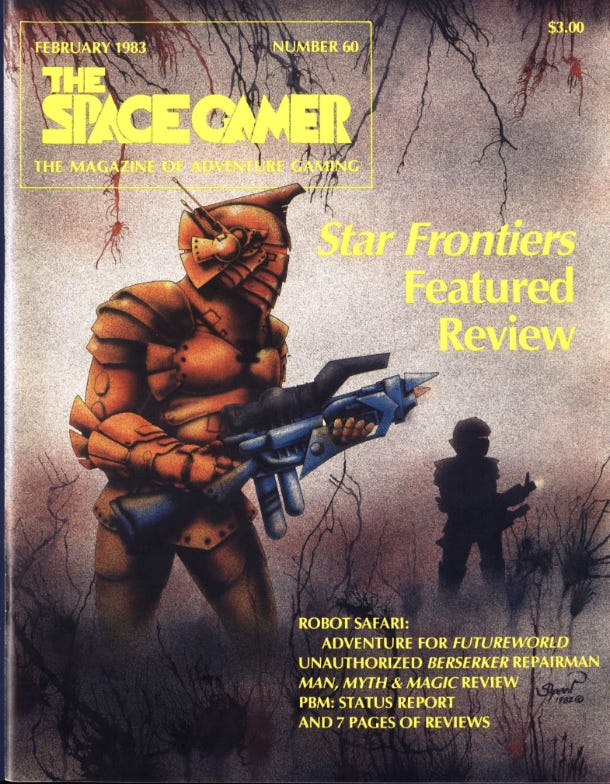

But the May/June issue of Fire and Movement only gives us a part of the story. It doesn’t truly show how desperate TSR was to diversify their brand, and how much internal strife existed at the company. Those elements can be seen in old issues of The Space Gamer. In issue 60 of TSG, John Rankin writes an article about a visit by TSR employees to Dallas where TSR Vice-President Duke Seifried were to meet with Heritage-USA and where there were possibly discussions for TSR to purchase Heritage or to enter into a joint venture with them. John Rankin’s article states:

Heritage USA still owed Duke Seifried money from his time with the company, and that Duke was a stockholder in the company.

TSR was very much in need of a miniatures company if they wanted to diversify.

No meeting between TSR and Heritage actually occurred, though Duke did likely get information from them as a stockholder.

TSR “left no broken hearts in Dallas. But they didn’t make any new friends either.”

There is a sense of some instability at TSR, and they are seen as not wanting to lead the industry rather just to “control it.”

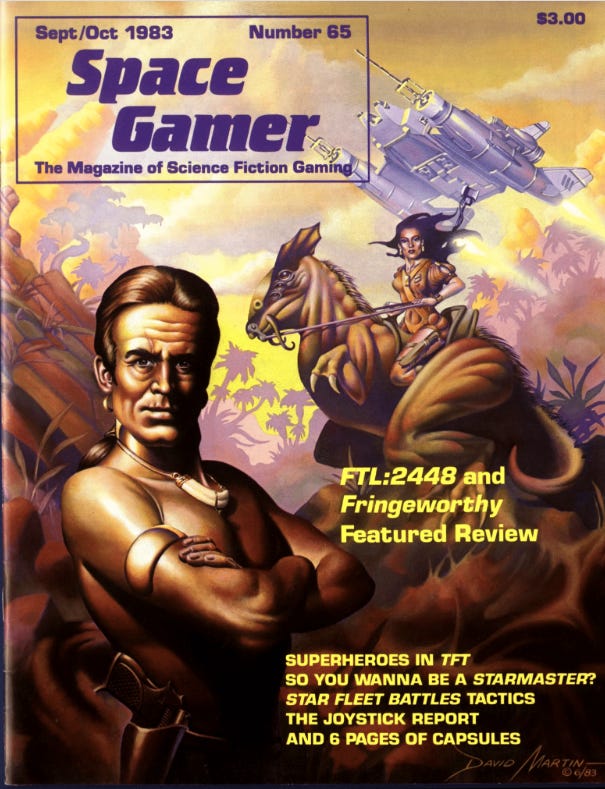

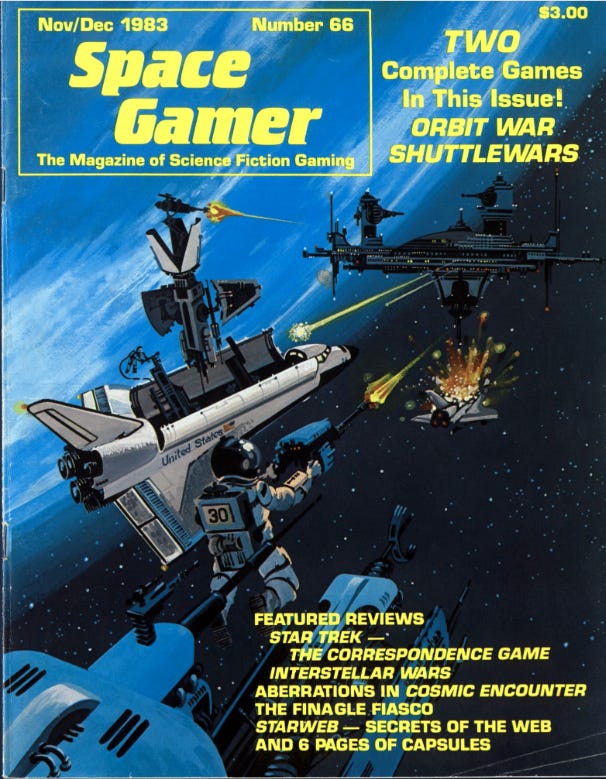

This all seems like a relatively mundane deal gone bad...until one looks at other issues discussing TSR. By issue 65 of The Space Gamer, the internal strife at TSR comes to the fore. In that issue, the following facts are reported.

TSR released 40 of its employees in June of 1983. Among these employees was Duke Seifried.

TSR was reorganized into 4 companies.

TSR Public Relations director Dietur Sturm described TSR finances as, “More or less, what you’re looking at is money coming into the company from sales and not focused properly...Sales are there as far as the distributors and retailers and stores (are concerned); they have nothing to worry about.”

This news demonstrates a number of problems within TSR. There is obviously internal strife. The firing of Seifried and the “banishing” of Gygax to Los Angeles hint at that. The company also clearly had no idea how to maintain and expand their product lines. They purchased a needlepoint company for goodness’ sake! Why? What synergy could that provide?

They purchased SPI, a company that had a rich catalog of war games but that also had a Fantasy Roleplaying Game called Dragon Quest. Picking and choosing SPI games to reissue in deluxe editions would have been a wonderful way to synergize their new purchse, but supporting the SPI role playing game would have possibly meant cannibalizing their own product lines. Cannibalization is when you issue products that fill the same market niche of existing products and result in the expenditure of unnecessary capital that deminishes returns on investment. Old TSR did plenty of pseudocannibalization with their release of multiple games systems for various genre games. I loved that they did that, but their core books for D&D would have sold even more if Top Secret required their use.

In addition to having no plans for a lot of the product lines they purchased TSR had no plans to retain the talented employees acquired in the SPI purchase, and in fact eventually fired everyone they hired from SPI and even refused to support life time subscriptions to SPI’s magazine Strategy & Tactics. TSR did everything they could to alienate the customer base of the company they had just acquired, and they did this while they were “reorganizing” to end an outpouring of money. TSR was in constant need of revenue to stay afloat. They were selling a ton of product, but they also weren’t developing products with any logical consistency. These are trends that wouldn’t end any time soon. You can read Ryan Dancey’s financial audit of TSR when Wizards of the Coast purchased them to see just how much this remained a problem in 1997 under Lorraine Williams.

I think that the purchses was an example of TSR not wanting to be the market leader, rather the market controller. They wanted to push competition out of the market, rather than innovate and create. This explains why they boycotted GAMA and demanded D&D not be played at Origins. Why they had no plans for talent retention. Why didn’t publish many of the large catalog of products they acquired. TSR doesn’t seem to have been logical in the determination of the size of print runs. They cannibalized product lines -- even in the Blume/Gygax era though this became disastrous in the Williams era. As much as I love TSR’s many settings having the Forgotten Realms, Greyhawk, Mystara, Hollow World, Birthright, and Dark Sun all as simultaneous fantasy setting product lines is a case study definition of cannibalizing product lines. Having “Basic,” “Expert,” “Companion,” and “Master” D&D as well as Advanced D&D -- let alone a 2nd edition -- is also a case study definition.

The company produced great games, but they were not managed well at all. Bad management is endemic throughout the rpg industry. It is an industry primarily run by hobbyists and not business people. This is a creative boon, but a business curse.

Lots of great insight in this article and those classic covers kick ass!

Good read. The needlepoint company was almost certainly some kind of "favor" to someone with a cash payout of some kind