Board Game Review: ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK from TSR

The publisher of D&D releases a board game based on a John Carpenter film. How does it fare?

Robert Meyer Burnett, the director of Free Enterprise, has argued that 1982 is the "Best Geek Movie Year Ever," but 1981 is a year filled with so many fantastic geek movies. In fact, I might go so far as to say that 1981 is my choice for Best Geek Movie Year Ever, I’ll write a future post on the topic, but the central question of any such analysis is the following, "Is Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan sufficiently great as a geek movie to displace Scanners, The Howling, Nighthawks, The Hand, Outland, Dragonslayer, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Clash of the Titans, Heavy Metal, An American Werewolf in London, Enter the Ninja, Halloween II, Time Bandits, the American release of the original Inglorious Bastards, and not least of all Escape from New York?" That's a pretty significant list to overcome, and it doesn't include the fact that The Evil Dead was premiered in Detroit on October 15th of 1981 (it wasn't officially released until 1983). Nor does it include the fact that 1981 is also the year a number of my other favorite films were released, including: Excalibur, Fort Apache the Broxn, The Dogs of War, Thief, Stripes, Southern Comfort, Gallipoli, The Fox and the Hound, The Road Warrior, Knightriders, Roar, and Taps. Roar alone deserves special attention as one of the most insane films ever made.

Most of these movies will please any viewer who is willing to give into their “Primal Screen” and step away from pretense, and quite a few stand the test of time as just plain excellent movies or have like The Fox and the Hound been the fertile soil that many talented film makers grew from. 1981 was a great year to fall in love with movie theaters. It was also a great year to become a John Carpenter fan, while 1996 was a good year to ask oneself "Why do I like John Carpenter again?." Those moments of doubt, which usually come after watching Escape from LA., are usually best cured by a viewing of Escape from New York. Both feature similar casts and similar stories, but Escape from New York presents its subject matter as an actual possibility while Escape from LA falls into what David Foster-Wallace calls the post-modern trap and treats its subject as a joke.

Escape from New York cost around $6 million to make, and raked in approximately $25.2 million in the box office. But in a year where the average movie ticket price was $2.78 (compared to today's $9.00+), that's the equivalent of about $93 million today for a $22.17 million cost. Given the film's relative popularity, especially among "geek" audiences, it is no surprise that TSR (at that time a growing gaming company in the United States and the creators of Dungeons and Dragons) would take the plunge and acquire a license to produce a board game based on the film. TSR eventually manufactured a roleplaying game based on the Indiana Jones franchise that I’ll be covering in my series on license role playing games.

Gamers have had a long history of railing against licensed games, particularly games based upon a film property. From E.T. for the Atari 2600 to the slight misfire that was the Dr. Who roleplaying game by FASA, every gamer has his nightmare licensed game story. While it is true that gamers have been the victims of many a bad licensed product, they have also been blessed with some excellent games based on licenses. From West End Games' Star Wars and FASA’s Star Trek roleplaying game (they knocked this one out of the park) to the various Conan based table top roleplaying games, gamers haven't always suffered when a license was involved.

So where does Escape from New York board game fall in the spectrum of license based games?

The first thing that strikes a potential player of the game is the sub-par graphic on the box cover (above). One appreciates that TSR did more than simply reuse imagery from the press kit when designing the cover, but the cover doesn't really do much to invite game play. The palette of colors selected is uninspiring and the accuracy of the anatomy of the characters portrayed on the cover leaves something to be desired. If one where to merely judge a game by its cover, the verdict would no be a friendly one to the Escape from New York board game. That said, production values of most games were often low at the time, especially when the game wasn't being produced by one of the major board game manufacturers like Milton Bradley or Parker Brothers.

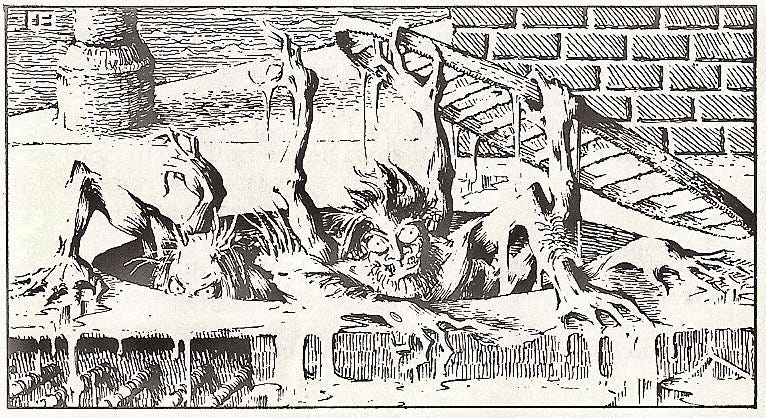

Looking inside the rulebook one finds the graphics of the product increasing in quality significantly with Erol Otis presenting his version of the Crazies. Otis' work is always a little weird, but his stylings work well for these horrific sewer dwellers -- adding a layer of the almost supernatural. This is just downright creepy.

Complementing the bizarre is the workmanlike and proficient illustration by Bill Willingham. Willingham, like Otis, is a fan favorite artist for those D&D players who cut their teeth on the legendary "red box" edition of the game, but Willingham's work here is very serviceable.

It provides a better semblance of the tone the game should convey in it's play than the cover art, and its representation of perspective doesn't push the viewer out of the illustration. One only gets a taste of Willingham's sizable talent in this piece and if you want to see him progress into one of the greats, you should check out his 1984 comic book series The Elementals.

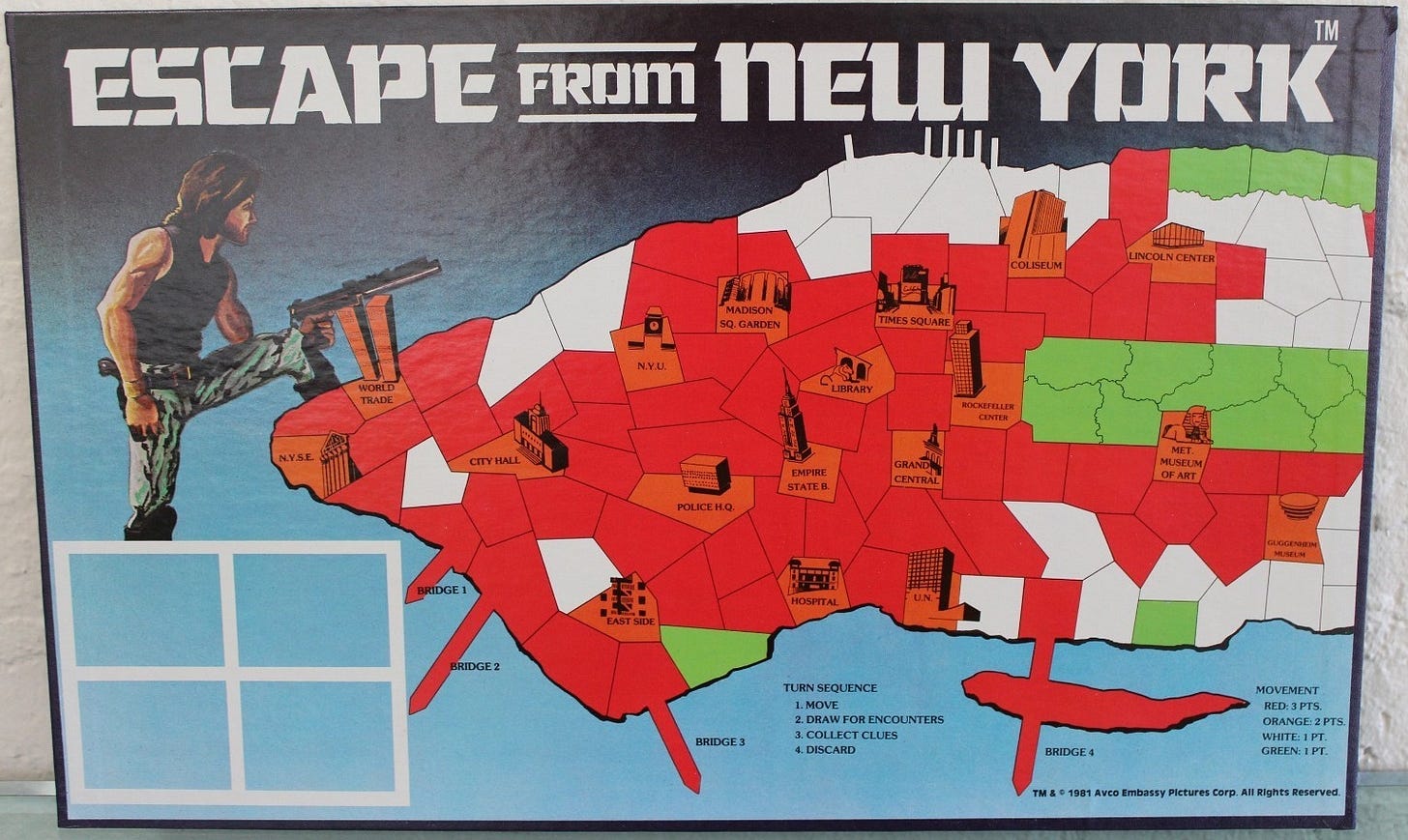

Graphic presentation is an important component of game presentation, but it is only one factor of game design and often has little to no influence over game play. One receives few if any hints as to actual game play from the art on a box cover or within the rule book. The same cannot be said of the game board itself. While the art on a game board may, or may not, influence the actual mechanics of game play, staring at an image for an hour or so can affect whether you are willing to reopen a game and revisit the content. Good rules, and play, can overcome a bad board, but game board design should be a central consideration for board game design. The board doesn't have to be anything flashy, but it should be presentable. When it comes to illustration, presentable is what Escape from New York offers, but it is the game design elements that begin to hint that this game might be bringing more to the table than the merely passable graphics would have hinted. Notice that there are areas of different colors on the game map. The isle of Manhattan has been divided into areas of different colors. Sometimes such differences are only for show, but in the case of Escape these elements signify how the areas affect gameplay.

Escape from New York falls into the broad category of "Adventure Board Game." More specifically, it falls into the category of "Early Adventure Board Game." These are games that fall somewhere between traditional track movement board games like Chutes and Ladders and more complex table top gaming like Avalon Hill's The Mystic Wood. Adventure board games combine traditional board gaming elements with wargame concepts and overlay an additional role playing component. The first of these games is, arguably, TSR's Dungeon board game.

Like a track movement game, adventure board games tend to use some form of randomization for movement on a map. Like traditional wargames, players can specifically target the opponents pieces and attack them. Unlike either of the above, adventure board games players also have encounters with non-player obstacles which must be individually overcome as distinct narrative elements. In other words, the game attacks the player's pieces, or provides narrative moments, which the players must overcome and interact with in order to complete the game. Additionally, players of an adventure board game take on the "role" of the character their piece represents.

In the case of Dungeon, the players take on the roles of fighters, wizards, and elves exploring a dungeon in the quest for gold. In the case of Escape from New York, the players all take on the role of Snake Plisskin -- with only one player representing the "real Snake." That player being the one who finishes the game. Given the reaction most people have when first meeting Snake in the movie, this conceit is quite appropriate.

The goal of each player in the game is the same as Snake's mission in the movie. The players are all attempting to find the President and get him off of the criminal infested prison island of Manhattan. Failing that, they are to bring the tape the President was carrying. Failing that...you die, they die, everybody dies.

To find either the President or the Tape, the players must acquire clue cards which contain information as to the possible location of one or the other. They do this my moving around the isle of Manhattan to the various orange colored locations -- places like the Lincoln Center. Movement is determined by two factors. First, the role of two die determines how many "movement points" the player has this turn. Second, each space costs a different number of movement points to pass through. Red spaces, which likely signify dangerous areas where one must move slowly, cost 3 points of movement. Orange spaces, which signify places where one can find clues and/or the President/Tape, cost two spaces of movement. Green and White spaces, which are relatively safe areas, cost only one space of movement to pass through.

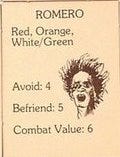

If the player ends their turn in an orange location, they find a clue. If they find enough clues, they can find the President or Tape at a location. Regardless of the color of location the character lands upon, and before any clues can be discovered, the player must draw an encounter card, like the Romero card below.

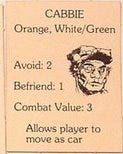

Encounter cards contain information about the areas where the encounter must be engaged. Romero must be engaged no matter which location you are on, but the Cabbie card is only encountered in Orange, White, and Green locations. If you are not on a space where the encounter can happen, you do not encounter that card and can move on about your business of finding the President or Tape. Sometimes it's good to miss encounters, and sometimes it's not so good.

Players don't tend to want to encounter Romero, but they do tend to desire a chat with Cabbie. This brings us to the next component of game play. Once a player has determined that he must engage with an encounter, that player has three options (listed on both the Romero and Cabbie cards). The player can try to avoid the encounter, befriend the encounter, or enter combat with the encounter. If the player succeeds at avoiding the encounter, nothing more happens. If they befriend the encounter, they get to keep the card and use any benefits conferred. If they fail at either of these tasks, they must fight the card but the fight will be more difficult than if they merely chose to fight in the first place. All of these tasks are resolved by rolling a single die and adding any modifiers for weapons and allies. If you lose a combat, you loose a card in your hand. If you have no cards in your hand...you're dead.

Gameplay is simple and fast paced. Figuring out how and where to move is the most complex task of gameplay and adds some interesting strategic decisions. Do you know where the President is, but want to mislead the other players before you grab him and make a run for it? Okay, but you might meet up with Romero or The Duke who are very difficult encounters. Do you risk red areas after you have the President in order to take a more direct route out of New York? Did you roll enough movement points to enter an orange space, and thus be able to attain a clue?

I was surprised at how deep the game play was on this simple adventure board game. More recent games in the genre are more complex and have better graphic representation, but this game is surprisingly fun. It maintains the tone and feel of the subject it is based on, while still being a playable game. It's rare enough that one finds that to be true in licensed games, that one should treasure the moments when one finds a game that accomplishes that small task.

RATING: B- Playable and fun, but one for a themed game collection rather than a general one. If you like the movie, and can find the game for a reasonable price ($50 - $75) snap it up. There’s a new semi-cooperative Escape from New York board game designed by Kevin Wilson, one of the premiere modern Adventure game designers who designed Descent, but I haven’t had a chance to play that yet. In that game, players can play a number of different characters in the game.

I haven't played the game since I was a kid. Your review makes me want to dig it up and give it a try again.

Sounds like an interesting game. Being a fan of the movie would enjoy playing the game.